Painting Qantas chief executive Alan Joyce as a superhero is part of a long Australian tradition

- Written by Claire Wright, Research Fellow, Centre for Workforce Futures, Macquarie University

Alan Joyce is Australia’s highest-paid chief executive.

Alan Joyce is one of the Financial Review’s ten most covertly powerful people.

Alan Joyce writes heartwarming notes to children.

Alan Joyce is getting married.

And he is apparently some sort of superhero.

Something about chief executives brings forth testimonials like this, published in the News Corporation tabloids last month, which followed the revelation that Joyce was Australia’s highest paid corporate chief (taking home A$24 million in 2018-19).

Penned by Angela Mollard, a journalist specialising in celebrities, it said he had

turned around a failing company, put thousands of dollars in shareholders’ pockets, boosted the superannuation of Mr and Mrs Average and prevented thousands from losing their jobs.

Joyce, and all the best chief executives, she argued, were

alchemists, strategists, innovators and geniuses. They have the sort of agile brains that produce solutions to problems which seem intractable. They lead not from a textbook but from an internal well of brilliance that seems constantly replenished.

Further, executives like Joyce deserved to be rewarded for

the risks they take, the entrepreneurship they exhibit, the education they’ve invested in and the particular brand of brilliance that comes along all too rarely.

It’s been said before

I’ve been examining the language used to describe Australia’s elite executives over the past 100 years, and what’s being said about Joyce is familiar - right down to the use of the word “genius”.

This kind of talk, repeated for more than a century now, leads us astray if we keep repeating it. It creates misunderstandings about how large companies work. Chief executives aren’t superhuman, their characteristics are not those of their companies, they don’t single-handedly determine the fate of those companies or personally employ their workers, they aren’t necessarily selfless or patriotic, and they don’t necessarily have the best interests of the nation at heart.

Read more: CEOs who take a political stand are seen as a bonus by job applicants

Sir Charles Mackellar, chairman of the Mutual Life & Citizens’ Assurance Company and a director of a host of other companies including the Colonial Sugar Refining Company was labelled a “genius” when he died in 1914.

FA Govett, the London-based head of Australia’s Zinc Corporation was labelled as a “man of exceptional ability” in 1926.

Often they had higher ideals.

Sir William Lennon Raws, a director of four of Australia’s biggest companies including BHP and Elder Smith, was a “well-meaning capitalist with a dream”.

Like Joyce and his contemporaries that work their “butts off to do the right thing”, Raws was

palpably rich and could be richer; but I doubt if the making of another million would be as much to him as the achievement of one of his cherished hopes.

It’s their own work

Daily Telegraph, May 6, 1926

Executives have long been seen as the sole reason for their company’s success. In 2019, Joyce single-handedly “took a beleaguered company and transformed it”.

Similarly, in the late 1800s, BHP director William Jamieson was solely responsible for the development of the Broken Hill region.

Robert Philp of Burns Philp and Company was an Australian patriot who “controlled her destinies during a critical period”.

Industrialist and car manufacturer Edward Holden worked tirelessly to “benefit the state and the company”.

Corporate director and university chancellor Sir Normand Maclaurin was “endowed with talents of a very high order […] having at heart the welfare of the nation”.

They’re exceptional

Joyce’s success might be due to his “big dick energy”, but he wasn’t the first. In the early 1900s, Joseph Pratt – director of the National Bank of Australasia, the Land Mortgage Bank, the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company and Metropolitan Gas Company – was described in the most masculine of terms as a big man

tall, erect, well-made and muscular. He has a pleasant, manly face, indicative of straightforwardness and goodness of disposition, and upon which grows a russet beard, containing a few grey hairs…

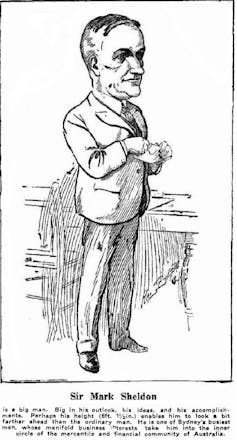

Sir Mark Sheldon - chairman of the Waterloo Glass Bottle Works, a director of the Australian Bank of Commerce, and vice president of the Sydney Chamber of Commerce - also also big ,

big in his outlook, his ideas, and his accomplishments. Perhaps his height (6 feet, 1.5 inches) enables him to look a bit farther ahead than the ordinary man

Painting corporate chiefs like this gives corporations a human face. It helps convince customers and investors that their money is in safe hands. If Alan Joyce is a ‘good man’, then the Qantas Group is seen as a good company.

Read more:

Swollen executive pay packets reveal the limits of corporate activism

It also makes executives untouchable. After all, if they are blessed with unique or exceptional abilities, and if their company is doing well (whatever the reason), it is hard to argue with the millions being spent on them.

Even if it’s $24 million, even if it’s more.

Daily Telegraph, May 6, 1926

Executives have long been seen as the sole reason for their company’s success. In 2019, Joyce single-handedly “took a beleaguered company and transformed it”.

Similarly, in the late 1800s, BHP director William Jamieson was solely responsible for the development of the Broken Hill region.

Robert Philp of Burns Philp and Company was an Australian patriot who “controlled her destinies during a critical period”.

Industrialist and car manufacturer Edward Holden worked tirelessly to “benefit the state and the company”.

Corporate director and university chancellor Sir Normand Maclaurin was “endowed with talents of a very high order […] having at heart the welfare of the nation”.

They’re exceptional

Joyce’s success might be due to his “big dick energy”, but he wasn’t the first. In the early 1900s, Joseph Pratt – director of the National Bank of Australasia, the Land Mortgage Bank, the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company and Metropolitan Gas Company – was described in the most masculine of terms as a big man

tall, erect, well-made and muscular. He has a pleasant, manly face, indicative of straightforwardness and goodness of disposition, and upon which grows a russet beard, containing a few grey hairs…

Sir Mark Sheldon - chairman of the Waterloo Glass Bottle Works, a director of the Australian Bank of Commerce, and vice president of the Sydney Chamber of Commerce - also also big ,

big in his outlook, his ideas, and his accomplishments. Perhaps his height (6 feet, 1.5 inches) enables him to look a bit farther ahead than the ordinary man

Painting corporate chiefs like this gives corporations a human face. It helps convince customers and investors that their money is in safe hands. If Alan Joyce is a ‘good man’, then the Qantas Group is seen as a good company.

Read more:

Swollen executive pay packets reveal the limits of corporate activism

It also makes executives untouchable. After all, if they are blessed with unique or exceptional abilities, and if their company is doing well (whatever the reason), it is hard to argue with the millions being spent on them.

Even if it’s $24 million, even if it’s more.

Authors: Claire Wright, Research Fellow, Centre for Workforce Futures, Macquarie University