It's Newstart pay rise day. You're in line for 24 cents, which is peanuts

- Written by Peter Martin., Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Newstart recipients and other Australians on benefits get their half-yearly pay rise today (and also on March 20). This one is vanishingly small.

Announced very quietly by Social Services Minister Anne Ruston earlier this week, it amounts to just A$3.30 per fortnight for someone on the Newstart unemployment benefit.

That’s $1.65 per week, less than 24 cents per day.

It’s enough to buy about 36 peanuts – or more if you buy them in bulk.

More galling still for Australians on Newstart, age and disability pensions will increase by twice as much - $6.80 per fortnight, an increase the government was keener to highlight in its press release than the increase in Newstart.

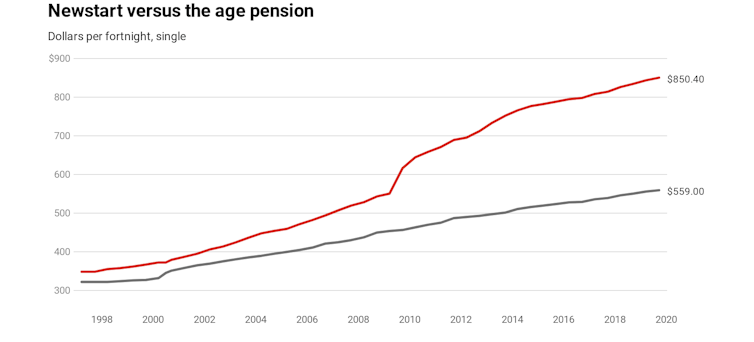

It is hard to comprehend how it could have come to this. Back in 1997 Newstart and the pension were about the same in dollar terms. Each was probably somewhat less than a single person needed to live on.

How did it come to this?

Then the Howard government effectively froze Newstart, forevermore increasing it only in line with inflation (which back then was typically 2.5% per year) while using a formula that lifted pensions in line with wage growth or inflation, whichever was the bigger (back then wages were growing by more than 3% per year).

The difference wasn’t big, but over the past two decades it has compounded. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd helped it along in 2009 by a one-off $64 per fortnight increase in the single pension, unmatched by an increase in Newstart.

Source: Ben Phillips ANU, DSS

It means that from today the single pension will be $850.40 per fortnight, while the single Newstart payment will be $559 – a mere two-thirds of the pension.

And it’ll get worse.

Because inflation is low, and each low increase is off what is now a much lower base than the pension, Newstart increases are small while pension increases are twice as big.

Read more:

FactCheck: do 99% of Newstart recipients also receive other benefits?

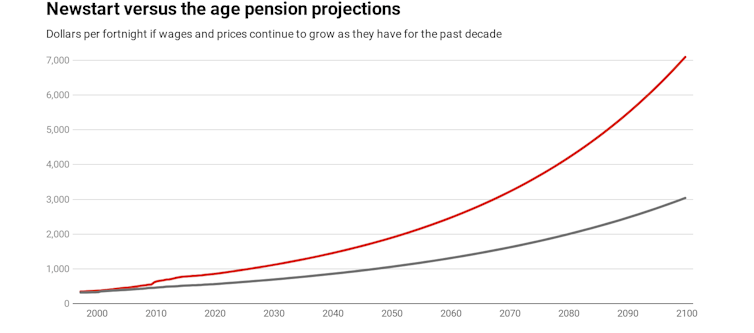

If prices and wages continue to grow at the rates they have over the past decade (2.1% per year for prices, 2.7% for wages) by 2070 Newstart will be just half of the pension. By the end of the century it’ll be just two fifths of the pension.

Source: Ben Phillips ANU, DSS

It means that from today the single pension will be $850.40 per fortnight, while the single Newstart payment will be $559 – a mere two-thirds of the pension.

And it’ll get worse.

Because inflation is low, and each low increase is off what is now a much lower base than the pension, Newstart increases are small while pension increases are twice as big.

Read more:

FactCheck: do 99% of Newstart recipients also receive other benefits?

If prices and wages continue to grow at the rates they have over the past decade (2.1% per year for prices, 2.7% for wages) by 2070 Newstart will be just half of the pension. By the end of the century it’ll be just two fifths of the pension.

Ben Phillips, Peter Martin ANU, DSS, ABS

If it can’t continue, it won’t

Herbert Stein was an economic advisor to US presidents Nixon and Ford. These days he is best remembered among economists for Stein’s Law, which says pithily:

If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

It’s a warning against the dangers of extrapolations of the kind I have just done, and also a guide to the future. A Newstart rate of just two fifths of the pension, way below everyone else’s standard of living, would be intolerable.

The formula will change well before it gets that bad. It’ll have to.

John Howard himself said so last year:

I was in favour of freezing when it happened, but I think it has probably gone on too long.

The question is how it will change. Labor promised a review and an increase during the last election.

The Coalition is holding firm, although it can’t if it continues to remain in office.

A decade ago the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development warned that Newstart was low enough to raise “issues about its effectiveness in providing sufficient support for those experiencing a job loss, or enabling someone to look for a suitable job”.

The Australian Council of Social Service wants the government to lift Newstart by $150 per fortnight to $709, still well short of the pension, and afterwards to lift it in line with the pension and wages, so that it never falls further behind.

It wants the same for Youth Allowance, Austudy, Abstudy, Sickness Allowance, Special Benefit, Widow Allowance and Crisis Payment, which all move in line with Newstart.

The hit to the budget would be $3.3 billion per year, small enough to be funded by projected surpluses.

Read more:

Are most people on the Newstart unemployment benefit for a short or long time?

And it would get smaller. Deloitte Access Economics says that after some years about $1.5 billion per year would return to the budget in extra tax as Newstart recipients and the other beneficiaries spent what they were given and boosted economic growth.

They’d have to.

Ben Phillips, Peter Martin ANU, DSS, ABS

If it can’t continue, it won’t

Herbert Stein was an economic advisor to US presidents Nixon and Ford. These days he is best remembered among economists for Stein’s Law, which says pithily:

If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

It’s a warning against the dangers of extrapolations of the kind I have just done, and also a guide to the future. A Newstart rate of just two fifths of the pension, way below everyone else’s standard of living, would be intolerable.

The formula will change well before it gets that bad. It’ll have to.

John Howard himself said so last year:

I was in favour of freezing when it happened, but I think it has probably gone on too long.

The question is how it will change. Labor promised a review and an increase during the last election.

The Coalition is holding firm, although it can’t if it continues to remain in office.

A decade ago the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development warned that Newstart was low enough to raise “issues about its effectiveness in providing sufficient support for those experiencing a job loss, or enabling someone to look for a suitable job”.

The Australian Council of Social Service wants the government to lift Newstart by $150 per fortnight to $709, still well short of the pension, and afterwards to lift it in line with the pension and wages, so that it never falls further behind.

It wants the same for Youth Allowance, Austudy, Abstudy, Sickness Allowance, Special Benefit, Widow Allowance and Crisis Payment, which all move in line with Newstart.

The hit to the budget would be $3.3 billion per year, small enough to be funded by projected surpluses.

Read more:

Are most people on the Newstart unemployment benefit for a short or long time?

And it would get smaller. Deloitte Access Economics says that after some years about $1.5 billion per year would return to the budget in extra tax as Newstart recipients and the other beneficiaries spent what they were given and boosted economic growth.

They’d have to.

Authors: Peter Martin., Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University