As Scott Morrison heads to Washington, the US-Australia alliance is unlikely to change

- Written by David Smith, Senior Lecturer in American Politics and Foreign Policy, Academic Director of the US Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s official visit to Washington this week carries some prestige. It is just the second “official visit” (including a state dinner) by a foreign leader during the Trump presidency, and the first by an Australian since John Howard in 2006. Despite a rocky start, relations between Australia and the US have been uniquely smooth in the Trump era.

Many traditional allies have learned to endure constant insults from the president. Trump complains bitterly about allies taking advantage of the United States in trade deals and defence alliances. France, Germany, South Korea, Japan, Denmark, Canada, Mexico and the whole of NATO have all been on the receiving end of Trump’s scorn.

In contrast, the leaders of a select group of Middle Eastern allies – Saudi Arabia, Israel, the UAE, and Egypt – have enjoyed extravagant backing from Trump, born of a mutual hostility to Iran and Barack Obama.

Australia seems to be in its own category as a long-standing ally that rarely attracts the attention of the president. In the absence of either tantrums or patronage, business as usual has quietly continued.

Australia’s unique position may be largely because we have a trade deficit with the United States, rather than the other way around. This is an issue of core importance to Trump, and the US gets its fifth-largest trade surplus from Australia at US$7.8 billion.

Australia’s outgoing ambassador, Joe Hockey, has cultivated a genuinely warm personal relationship with Trump that lubricates various bargains. It’s impossible to imagine him suffering the same fate as the UK’s Kim Darroch.

Morrison also understands the usefulness of a close personal relationship with the president and has steadily worked on this. It helps that Trump believes he has some political affinity with him.

But the relationship between the Australian and American governments is much broader than the one between president and prime minister. It is conducted behind the scenes every day by public servants on both sides and reflects decades of cooperation. Earlier this year, pro-Australian forces in the US government successfully defused Trump’s irritation at the volume of Australian aluminium exports to the US. Australia remains the only country with a complete exemption from American steel and aluminium tariffs.

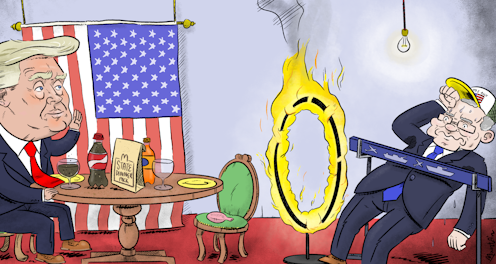

This very stability may limit the scope of what Trump and Morrison can talk about. Most issues are relatively settled. However, the US-China trade war, and Australia’s role in it, will almost certainly be a topic of conversation.

Given the risks to Australia from a trade war, some had hoped Morrison could influence Trump to de-escalate tensions. In June, Morrison warned against the development of a “zero-sum mindset” on trade. He told a London audience that the World Trade Organisation, then under attack from the US, needed support as the US-China trade conflict put prosperity and living standards at risk.

Read more: Trade war tensions sky high as Trump and Xi prepare to meet at the G20

Back then, there was still hope of an agreement, which now seems more remote than ever. Morrison seems resigned to an enduring conflict between two of our largest trading partners. He has said the world will have to get used to it and that the conflict is all about the need to enforce the rules of global trade on China.

Australia has long shared American concerns that China flouts the rules to the extent that it undermines the whole system. Indeed, Australians have sometimes worried that Trump’s obsession with trade deficits is actually a distraction from this deeper issue.

In February, Hockey warned Trump against making a deal with China that would reduce the deficit while leaving structural issues unaddressed. But none of this means Morrison would accept an invitation from Trump to join the US in the trade war.

Morrison has already committed Australian support to the US effort to guard oil shipments from Iranian seizures in the Strait of Hormuz. This is the kind of invitation Australia rarely refuses. A frigate, surveillance and patrol aircraft and some personnel will go to the Persian Gulf, though it is unclear when.

Read more: Infographic: what is the conflict between the US and Iran about and how is Australia now involved?

Other US allies, some of whom are signatories to the Iran nuclear deal, have declined to make even modest contributions such as these. They see the current crisis, correctly, as Trump’s fault and they fear provoking further conflict with Iran.

Even after Trump unilaterally withdrew the US from the Iran nuclear deal, reimposing sanctions that led to increased hostilities, the Morrison government opted to continue support for the deal, subject to Iranian compliance (which is now evaporating).

Both major parties are framing Australia’s support for the US in terms of our commitment to freedom of navigation and a rules-based international order.

Morrison is likely to reaffirm this commitment in Washington, without getting into discussions about why Trump withdrew from an agreement that his own intelligence agencies said was working. The recent demise of John Bolton as national security adviser will hopefully make it less likely that Australia faces any questions about deeper military involvement in the Gulf.

Morrison is keen to secure Trump’s first visit to Australia, for the President’s Cup golf tournament in December. While he lauds Trump as “a good president for Australia”, Australians are sceptical. A US Studies Centre poll in July found only 19% of Australians want to see Trump re-elected (that includes just 29% of Coalition voters).

In fairness to Trump, polls conducted in 2008 and 2012 found even smaller numbers of Australians wanted John McCain (16%) or Mitt Romney (5%) to win those presidential elections. The Republican Party this century has been well to the right of nearly every other mainstream conservative party in the world, including the Liberal Party.

Trump isn’t the first deeply unpopular president Australia has seen and he won’t be the last. In the 2019 Lowy Institute Poll, 64% of respondents say Australia “should remain close to the United States under President Donald Trump”.

There is no danger of that changing under Morrison.

Authors: David Smith, Senior Lecturer in American Politics and Foreign Policy, Academic Director of the US Studies Centre, University of Sydney