Twenty years after independence, Timor-Leste continues its epic struggle

- Written by Sara Niner, Lecturer and Researcher, School of Social Sciences, Monash University

On August 30, Timor-Leste will celebrate the referendum that gave it independence from Indonesia. For the people of this small island, it has been a long battle – one that continues today. You can read our companion story on the island nation’s vexed relationship with Australia here.

Indigenous myth attributes the high mountain chain that runs like a spine down the centre of the crocodile-shaped island of Timor to Mother Earth’s dying movements when she retreated underground. This mountain chain is more pronounced in the east, in the territory of Timor-Leste, and often protrudes directly down into the sea along the rugged northern coast.

The island is also surrounded by significant waters. To the south are the vast and disputed oil reserves. To the north is a deep exchange pathway for warm water moving from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean, creating conditions for a major “cetacean migration” highway for 24 different species of whale and dolphin.

Read more: For Timor-Leste, another election and hopes for an end to crippling deadlock

In 1944, the anthropologist Mendes Correa described the Portuguese colony of Timor as a “Babel … a melting pot”, and a diverse mix of traditions is still strongly felt today.

The island is a bridge between the Malay and Melanesian world and has as much in common with Pacific Island cultures as Indonesia. The diverse indigenous societies cross the spectrum of matriarchal and patriarchal organisation.

Women are accorded a sacred status within Timorese cosmology and the divine female element is prominent in much indigenous belief. Female spirits dominate the sacred world, while men dominate the secular world. So, while women may hold power in a ritual context, they generally do not have a strong public or political voice. But they are fighting to change this and now make up a third of members in the national parliament.

By the early 16th century, Portuguese colonisers arrived in the Spice Islands of which Timor was part. This was the beginning of a colonial relationship now 500 years old.

Revolts by Timorese against Portuguese rule were frequent and bloody. Famous Timorese rebel Dom Boaventura lost an armed uprising against his Portuguese colonisers in 1911, leaving East Timor to be ruled directly from Portugal by the fascist dictatorship of Salazar for most of the 20th century.

The marginal colony remained neglected and closeted from any modern liberalising trends. But in the early 1970s the Timorese independence movement Fretilin, partly inspired by Dom Boaventura, began to oppose Portuguese colonialism, while developing a revolutionary program that included the emancipation of women.

Rosa “Muki” Bonaparte was one of the founders of the nationalist movement and the leader of its women’s organisation. While Bonaparte participated directly in the struggle against colonialism, she also stood against “the violent discrimination that Timorese women had suffered in colonial society”.

Read more: Australia and Timor Leste settle maritime boundary after 45 years of bickering

After the colonial regime collapsed in 1974, a three-week civil war, secretly manipulated by Indonesian military agents, was the precursor to the larger war and invasion to come.

The victors of the civil war, Fretilin, reconstituted the faction of loyal Timorese soldiers serving in the Portuguese Army as resistance army Falintil. This army, and the civilian resistance, countered the massive and brutal attack of US-and-Australian-backed Indonesian military for 24 years. The horrors were kept as secret as possible, even to the point of covering up the deaths of those trying to report them, such as the “Balibo 5”.

After the Indonesian invasion of December 7 1975, much of the population of East Timor retreated to the mountains, with the resistance living in free zones for the next three years.

However, in November 1978, the Indonesian campaign of annihilation finally encircled the remaining resistance leadership and 140,000 civilians on Mount Matebian, in the east of the island. Most surrendered. They were placed in prisons and “resettlement camps” where many slowly starved to death. The violence of the 24-year Indonesian occupation affected and traumatised the whole of Timorese society.

After the collapse of the Suharto dictatorship in Indonesia in 1998, President B.J. Habibie agreed to let the Timorese decide their future in a ballot. In his honour, they recently named a bridge after him.

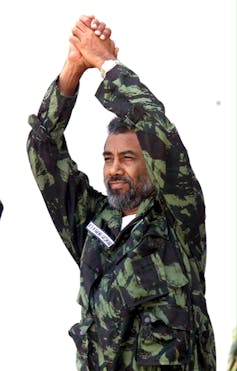

Xanana Gusmao was the key negotiator with Indonesia after the independence ballot.

AAP/EPA/John_Feeder

Xanana Gusmao was the key negotiator with Indonesia after the independence ballot.

AAP/EPA/John_Feeder

Timor’s pre-eminent leader, Xanana Gusmao, was the key negotiator with UN representatives. He conducted negotiations from his prison house in Jakarta where he’d been since 1992, serving a 20-year sentence for fighting Indonesian forces in his homeland. He persevered with ballot preparations despite growing Indonesian military and militia violence.

In the August 30 1999 referendum, nearly 80% of East Timorese voted for independence by indicating the blue and green National Council of Timorese Resistance (CNRT) flag on the ballot paper.

Extensive military and militia slayings followed the announcement of the vote. An estimated 1500 East Timorese were killed and more than 250,000 forcibly displaced into Indonesia. About 80% of infrastructure was destroyed. Survivors struggled to feed and look after their families while recovering psychologically from the mayhem.

Stories from the resistance period and 1999 are constantly remembered in Timor-Leste and are hugely significant in the new society. A hierarchy based on past service to the resistance has been established. Pensions and payments to male veterans are one of the biggest expenses for the government.

Anthropologists have described an indigenous belief that those who fought and sacrificed “purchased” the nation with their own lives and are owed a living.

Along with celebration there will be much reflection in Timor in the next weeks about the last 20 years of building a nation from “zero” and the 24 years of struggle that came before that. It will consider what they have achieved and what still needs to be done.

Hopefully, Timor-Leste can build a free and fair future for the over 1 million citizens, 60% of them under 18. They include many inspiring, educated young leaders who are ready to take up the responsibility.

As we watch and cheer from the sidelines, we hope for a less eventful and more peaceful future for all Timorese.

Authors: Sara Niner, Lecturer and Researcher, School of Social Sciences, Monash University