Southeast Asia was crowded with archaic human groups long before we turned up

- Written by João Teixeira, Research associate, University of Adelaide

Around 55,000-50,000 years ago, a population of modern humans left Africa and started on the long trek that would lead them around the world. After rapidly crossing Eurasia and Southeast Asia, they travelled through the islands of Indonesia, and eventually as far as the continent of Sahul – modern-day Australia and New Guinea.

Their descendants are the modern human populations found right across this enormous region today.

In new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, we detail how during this remarkable journey the ancestors of modern humans met and genetically mixed with a number of archaic human groups, including Neandertals and Denisovans, and several others for which we currently have no name. The traces of these interactions are still preserved in our genomes.

For example, all modern non-African populations contain about 2% Neandertal ancestry. This strong universal signal shows that the original Neandertal mixing event must have happened just after the small founding population left Africa.

Read more: When did Aboriginal people first arrive in Australia?

We can even use the Neandertal genetic signal to date when they left Africa. The large size of Neandertal DNA fragments in the genome of an ancient skeleton from southern Russia, which is 45,000 years old, shows that at most 230-430 generations could have passed since the initial mixing event (dating it around 50-55,000 years ago).

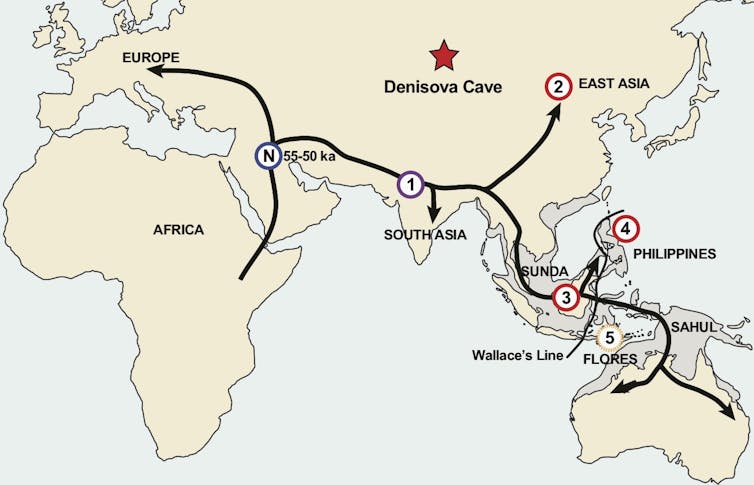

By analysing where the archaic genetic traces are found today (from previous genetic studies) and using paleovegetation maps that identify favourable savannah-like habitat along the route 55,000 years ago, we have reconstructed the likely geographic locations and number of the archaic hominin mixing events.

A map showing where the ancestors of modern humans appear to have met and mixed with archaic hominins.

Author provided

A map showing where the ancestors of modern humans appear to have met and mixed with archaic hominins.

Author provided

Leaving Africa

One of the first mixing events after the Neandertals appears to have taken place during the movement across southern Asia. The archaic human group involved was neither the Neandertals or Denisovans, but something similar – which currently has no name.

The genetic traces of this archaic group can be found from modern Punjabi and Bengal populations all the way through to New Guinea and Australia. As a result, we think this mixing event (marked 1 on the map) likely took place somewhere around northern India, which is the most “upstream” or westerly position it is first observed.

The ancestral population of modern humans then appears to have split as it moved across Asia with one pulse dispersing north into mainland Asia, where it met and mixed with a Denisovan group (marked 2 on the map). These Denisovans were genetically close to those we already know about from the Altai mountains. The traces of this event can be seen in East Asia today, and also in North and South America populations, who stem from northeastern Asia.

Island Southeast Asia was already crowded

The other pulse of modern humans headed south down the Malaysian Peninsula and into Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) where a big surprise awaited. They found the area was already crowded with different archaic human groups, including completely different species.

Recent fossil finds of small skeletons have shown that apparent relatives of Homo erectus (whose early fossils are common on Java) had survived on the Philippines and Flores (where they are known as “hobbits”) until around 52,000 years ago. Effectively right up until the modern humans arrived.

Read more: An incredible journey: the first people to arrive in Australia came in large numbers, and on purpose

The incoming modern human population apparently first met and mixed with a distant relative of the Denisovans in the area, leaving a signal in the genomes of Australo-Papuans and several ISEA populations. These signals are very different from the above East Asian mixing event, and instead come from a Denisovan relative that had separated genetically from the Altai/East Asian Denisovans around 280,000 years ago. This mixing event appears to have been somewhere around southern Malaysia/Borneo (marked 3 on the map).

Landfall in Australia

The wave of modern humans does not appear to have waited long to cross Wallace’s Line – the famous biogeographic barrier that effectively marks the edge of the ISEA landmasses joined together during past glacial periods, when sea levels were up to 120 metres lower.

We know this because a sudden appearance of archaeological sites right across Australia around 50,000 years ago indicates that modern humans had quickly crossed the marine gaps through ISEA.

While there is one much earlier Australian site, the 65-80,000 year old Madjedbebe rock shelter in Arnhem Land, it is a complete outlier to the rest of the Australian record and the age of the site has been queried.

While moving through ISEA, the modern human population appears to have met – and mixed with – two more archaic human groups. Hunter-gatherer populations in the Philippines preserve signals of yet another Denisovan-mixing event (marked 4 on the map), after they had diverged from the main wave of modern humans moving through ISEA.

Similarly, a genetic study of the short-statured modern day population that lives around the Flores cave where the tiny skeletons of the “hobbits” were found identified signals of DNA not from Homo erectus, the target of the study, but an enigmatic signal from something else. The source was neither Neandertal nor Denisovan but something of similar age – yet another currently unknown archaic group (marked 5 on the map).

Read more: Australia’s epic story: a tale of amazing people, amazing creatures and rising seas

The last survivors

What the different genetic studies across this region tell us is that the ancestors of modern humans appear to have met and mixed with four different archaic hominins, in at least six events. And this all happened in the very short window of time between leaving Africa 50-55,000 years ago, and arriving in Australia and New Guinea at most 5,000 years later.

Remarkably, none of these genetic mixing events appears to have involved fossil species in ISEA that we know were still around when modern humans arrived, such as Homo luzonensis (Philippines) and the Flores hobbits.

ISEA was clearly a very crowded place around 50,000 years ago, occupied by many different archaic human groups on many different islands. But shortly thereafter there was only one survivor: us.

Authors: João Teixeira, Research associate, University of Adelaide