NZ introduces groundbreaking zero carbon bill, including targets for agricultural methane

- Written by Robert McLachlan, Professor in Applied Mathematics, Massey University

New Zealand’s long-awaited zero carbon bill will create sweeping changes to the management of emissions, setting a global benchmark with ambitious reduction targets for all major greenhouse gases.

The bill includes two separate targets – one for the long-lived greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, and another target specifically for biogenic methane, produced by livestock and landfill waste.

Launching the bill, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said:

Carbon dioxide is the most important thing we need to tackle – that’s why we’ve taken a net zero carbon approach. Agriculture is incredibly important to New Zealand, but it also needs to be part of the solution. That is why we have listened to the science and also heard the industry and created a specific target for biogenic methane.

The Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Bill will:

- Create a target of reducing all greenhouse gases, except biogenic methane, to net zero by 2050

- Create a separate target to reduce emissions of biogenic methane by 10% by 2030, and 24-47% by 2050 (relative to 2017 levels)

- Establish a new, independent climate commission to provide emissions budgets, expert advice, and monitoring to help keep successive governments on track

- Require government to implement policies for climate change risk assessment, a national adaptation plan, and progress reporting on implementation of the plan.

Read more: Climate change is hitting hard across New Zealand, official report finds

Bringing in agriculture

Preparing the bill has been a lengthy process. The government was committed to working with its coalition partners and also with the opposition National Party, to ensure the bill’s long-term viability. A consultation process in 2018 yielded 15,000 submissions, more than 90% of which asked for an advisory, independent climate commission, provision for adapting to the effects of climate change and a target of net zero by 2050 for all gasses.

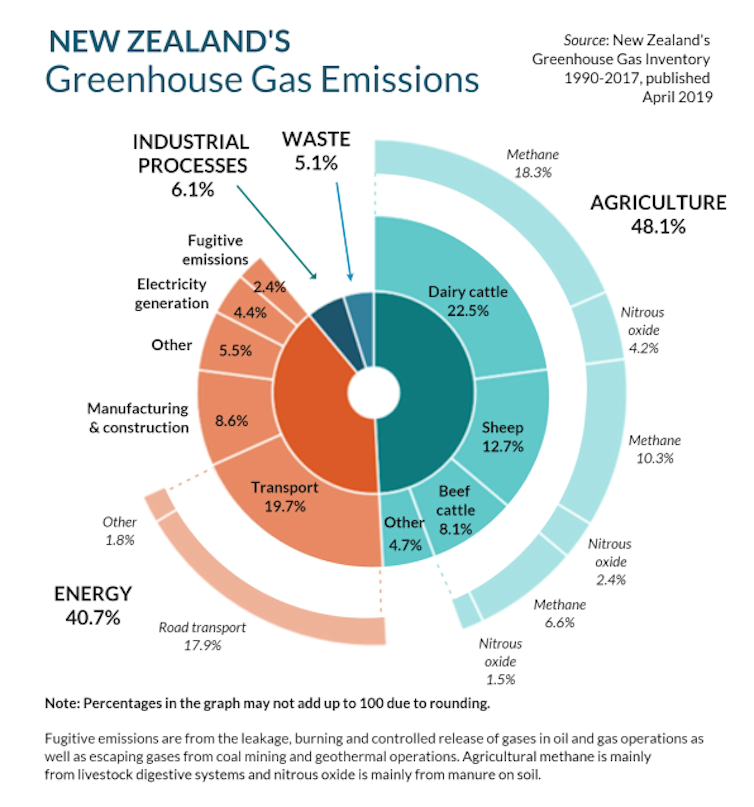

Throughout this period there has been discussion of the role and responsibility of agriculture, which contributes 48% of New Zealand’s total greenhouse gas emissions. This is an important issue not just for New Zealand and all agricultural nations, but for world food supply.

Ministry for the Environment, CC BY-ND

Another critical question involved forestry. Pathways to net zero involve planting a lot of trees, but this is a short-term solution with only partly understood consequences. Recently, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment suggested an approach in which forestry could offset only agricultural, non-fossil emissions.

Now we know how the government has threaded its way between these difficult choices.

Read more:

NZ's environmental watchdog challenges climate policy on farm emissions and forestry offsets

Separate targets for different gases

In signing the Paris Agreement, New Zealand agreed to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C and to make efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. The bill is guided by the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which details three pathways to limit warming to 1.5°C. All of them involve significant reductions in agricultural methane (by 23%-69% by 2050).

Farmers will be pleased with the “two baskets” approach, in which biogenic methane is treated differently from other gasses. But the bill does require total biogenic emissions to fall. They cannot be offset by planting trees. The climate commission, once established, and the minister will have to come up with policies that actually reduce emissions.

In the short term, that will likely involve decisions about livestock stocking rates: retiring the least profitable sheep and beef farms, and improving efficiency in the dairy industry with fewer animals but increased productivity on the remaining land. Longer term options include methane inhibitors, selective breeding, and a possible methane vaccine.

Ambitious net zero target

Net zero by 2050 on all other gasses, including offsetting by forestry, is still an ambitious target. New Zealand’s emissions rose sharply in 2017 and effective mechanisms to phase out fossil fuels are not yet in place. It is likely that with protests in Auckland over a local 10 cents a litre fuel tax – albeit brought in to fund public transport and not as a carbon tax per se – the government may be feeling they have to tread delicately here.

But the bill requires real action. The first carbon budget will cover 2022-2025. Work to strengthen New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme is already underway and will likely involve a falling cap on emissions that will raise the carbon price, currently capped at NZ$25.

Read more:

Why NZ's emissions trading scheme should have an auction reserve price

In initial reaction to the bill, the National Party welcomed all aspects of it except the 24-47% reduction target for methane, which they believe should have been left to the climate commission. Coalition partner New Zealand First is talking up their contribution and how they had the agriculture sector’s interests at heart.

While climate activist groups welcomed the bill, Greenpeace criticised the bill for not being legally enforceable and described the 10% cut in methane as “miserly”. The youth action group Generation Zero, one of the first to call for zero carbon legislation, is understandably delighted. Even so, they say the law does not match the urgency of the crisis. And it’s true that since the bill was first mooted, we have seen a stronger sense of urgency, from the Extinction Rebellion to Greta Thunberg to the UK parliament’s declaration of a climate emergency.

Read more:

UK becomes first country to declare a 'climate emergency'

New Zealand’s bill is a pioneering effort to respond in detail to the 1.5ºC target and to base a national plan around the science reported by the IPCC.

Many other countries are in the process of setting and strengthening targets. Ireland’s Parliamentary Joint Committee on Climate recently recommended adopting a target of net zero for all gasses by 2050. Scotland will strengthen its target to net zero carbon dioxide and methane by 2040 and net zero all gasses by 2045. Less than a week after this announcement, the Scottish government dropped plans to cut air departure fees (currently £13 for short and £78 for long flights, and double for business class).

One country that has set a specific goals for agricultural methane is Uruguay, with a target of reducing emissions per kilogram of beef by 33%-46% by 2030. In the countries mentioned above, not so different from New Zealand, agriculture produces 35%, 23%, and 55% of emissions, respectively.

New Zealand has learned from processes that have worked elsewhere, notably the UK’s Climate Change Commission, which attempts to balance science, public involvement and the sovereignty of parliament. Perhaps our present experience in balancing the demands of different interest groups and economic sectors, with diverse mitigation opportunities and costs, can now help others.

Ministry for the Environment, CC BY-ND

Another critical question involved forestry. Pathways to net zero involve planting a lot of trees, but this is a short-term solution with only partly understood consequences. Recently, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment suggested an approach in which forestry could offset only agricultural, non-fossil emissions.

Now we know how the government has threaded its way between these difficult choices.

Read more:

NZ's environmental watchdog challenges climate policy on farm emissions and forestry offsets

Separate targets for different gases

In signing the Paris Agreement, New Zealand agreed to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C and to make efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. The bill is guided by the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which details three pathways to limit warming to 1.5°C. All of them involve significant reductions in agricultural methane (by 23%-69% by 2050).

Farmers will be pleased with the “two baskets” approach, in which biogenic methane is treated differently from other gasses. But the bill does require total biogenic emissions to fall. They cannot be offset by planting trees. The climate commission, once established, and the minister will have to come up with policies that actually reduce emissions.

In the short term, that will likely involve decisions about livestock stocking rates: retiring the least profitable sheep and beef farms, and improving efficiency in the dairy industry with fewer animals but increased productivity on the remaining land. Longer term options include methane inhibitors, selective breeding, and a possible methane vaccine.

Ambitious net zero target

Net zero by 2050 on all other gasses, including offsetting by forestry, is still an ambitious target. New Zealand’s emissions rose sharply in 2017 and effective mechanisms to phase out fossil fuels are not yet in place. It is likely that with protests in Auckland over a local 10 cents a litre fuel tax – albeit brought in to fund public transport and not as a carbon tax per se – the government may be feeling they have to tread delicately here.

But the bill requires real action. The first carbon budget will cover 2022-2025. Work to strengthen New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme is already underway and will likely involve a falling cap on emissions that will raise the carbon price, currently capped at NZ$25.

Read more:

Why NZ's emissions trading scheme should have an auction reserve price

In initial reaction to the bill, the National Party welcomed all aspects of it except the 24-47% reduction target for methane, which they believe should have been left to the climate commission. Coalition partner New Zealand First is talking up their contribution and how they had the agriculture sector’s interests at heart.

While climate activist groups welcomed the bill, Greenpeace criticised the bill for not being legally enforceable and described the 10% cut in methane as “miserly”. The youth action group Generation Zero, one of the first to call for zero carbon legislation, is understandably delighted. Even so, they say the law does not match the urgency of the crisis. And it’s true that since the bill was first mooted, we have seen a stronger sense of urgency, from the Extinction Rebellion to Greta Thunberg to the UK parliament’s declaration of a climate emergency.

Read more:

UK becomes first country to declare a 'climate emergency'

New Zealand’s bill is a pioneering effort to respond in detail to the 1.5ºC target and to base a national plan around the science reported by the IPCC.

Many other countries are in the process of setting and strengthening targets. Ireland’s Parliamentary Joint Committee on Climate recently recommended adopting a target of net zero for all gasses by 2050. Scotland will strengthen its target to net zero carbon dioxide and methane by 2040 and net zero all gasses by 2045. Less than a week after this announcement, the Scottish government dropped plans to cut air departure fees (currently £13 for short and £78 for long flights, and double for business class).

One country that has set a specific goals for agricultural methane is Uruguay, with a target of reducing emissions per kilogram of beef by 33%-46% by 2030. In the countries mentioned above, not so different from New Zealand, agriculture produces 35%, 23%, and 55% of emissions, respectively.

New Zealand has learned from processes that have worked elsewhere, notably the UK’s Climate Change Commission, which attempts to balance science, public involvement and the sovereignty of parliament. Perhaps our present experience in balancing the demands of different interest groups and economic sectors, with diverse mitigation opportunities and costs, can now help others.

Authors: Robert McLachlan, Professor in Applied Mathematics, Massey University