Greens on track for stability, rather than growth, this election

- Written by Narelle Miragliotta, Senior Lecturer in Australian Politics, Monash University

The Greens are not expected to be the beneficiaries of a supposed surge in support for minor parties and independent candidates at this election. Since June 2017, Newspoll has rarely recorded the Greens’ primary vote much above 10%. And since October 2018, its vote has seemingly stagnated at 9%.

Relative to most other campaigns at this election, the Greens have had a strong run. They have avoided candidate debacles and contained the factional infighting that has blighted the Victorian and New South Wales divisions.

The party’s policy agenda contains strong appeals to its base (climate change and immigration) but also speaks to some of the concerns of Labor’s traditional working-class voter (industrial relations, education and health).

Read more: Shorten distances himself from Green overtures on climate policy

But the Greens seem quite circumspect. They are not strongly pushing for a formal coalition with Labor, nor are they talking up the prospects of a minority government. Party leader Richard Di Natale says he remains:

very confident that some time in the not-too-distant future majority governments will be the exception rather than the rule.

However, he is only talking about a “constructive” relationship with Labor.

Why are the Greens low-key?

When Di Natale was asked at the National Press Club on Wednesday about the party’s stalling electoral prospects, he struggled to articulate a reason. In the end, he countered that a single-digit outcome was likely “pessimistic”. Rather, he said:

I think we’ll continue to grow. Our trajectory has been characterised by consolidation in periods of rapid growth. And I’m sure one’s on the way very soon.

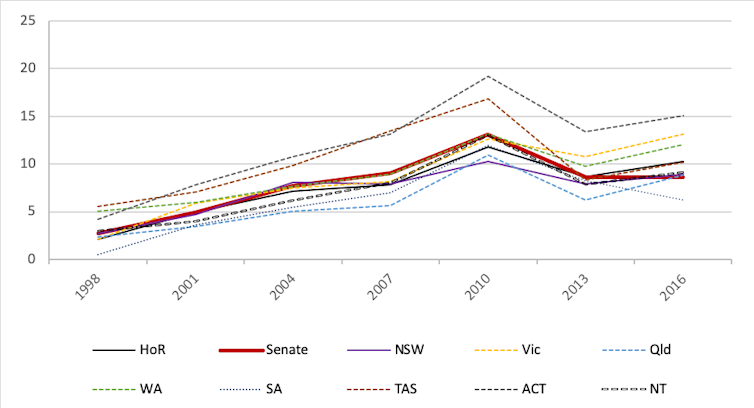

Federal voting data support Di Natale’s assessment about the arc of the party’s electoral performance. As the table below shows, the Greens’ primary vote in the House of Representatives (solid black line) and in the Senate (solid red line) has been broadly trending upwards since 1998.

Greens’ primary vote 1998-2016.

Author provided

Greens’ primary vote 1998-2016.

Author provided

But when you compare the party’s support at the state and territory level, then it becomes apparent that the strength of the Greens’ vote is mixed. The Greens poll consistently strongly in Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia and the ACT. However, in the case of the ACT, the territory’s constitutional status means the Greens are unable to convert their support into Senate representation.

In other states, the party has experienced some difficulty in gaining a comfortable footing, even if it does manage to elect senators. South Australian voters support non-major party candidates but have tended to prefer other vehicles, such as the now (mostly) defunct Australian Democrats and more recently the Nick Xenophon Team (now Centre Alliance).

A similar pattern is apparent in Queensland, but in this case much of the momentum for minor parties is behind right-tending parties, such as Katter’s Australia Party, the United Australia Party and One Nation. In NSW, the party’s support tends to run hot and cold.

What does this mean?

The degree of electoral support for minor parties (and independents), such as the Greens, is typically contingent on the electoral health of the major parties and the number of other non-major parties in the field.

An electorally diminished Labor is generally helpful for boosting the Greens’ primary vote. For example, at the 2010 federal election, the collapse in Labor’s primary vote (-5.40%) coincided with a spike in the Greens vote (+3.97%).

If Labor’s electoral malaise presents an opportunity for the Greens then a Labor recovery can limit the Greens’ growth prospects. In 2016, as Labor showed signs of electoral recovery (+1.34%), the Greens were able to achieve only modest growth in their primary vote. Although the Greens did increase their share of the vote (+1.58%), it was not enough to return it to their 2010 levels.

Even then, the 2013 election suggests there might be limits to the Greens’ ability to profit from swings against Labor. At this election, both parties suffered a swing against them, an outcome attributed to the parliamentary alliance/agreement that the two parties entered into following the 2010 election. What this suggests is that disgruntled Labor voters are probable but not “sure bets” for the Greens.

What might the Greens expect from the 2019 federal election?

It’s important to acknowledge that the above analysis frames the Greens’ gains and losses in relation to Labor’s electoral performance, which is only a part of the story. But it does point to the fact that the Greens’ ability to achieve a double-digit share of the national vote might depend on Labor crashing out, which is not supported by the polling in 2019.

Nevertheless, even if the Greens attain only a 9% share of the primary vote, this is likely to result in them retaining some of the six Senate vacancies they are defending. According to election analyst William Bowe:

Senate contenders will need something approaching 6% to be competitive, and around 8% to feel entirely confident.

Moreover, most analysts agree that Adam Bandt will retain Melbourne. His prospects were further strengthened when his Labor opponent quit after historical social media posts came to light.

And while high-profile Greens challengers, such as Julian Burnside in Kooyong, are not expected to win the lower house seats they are contesting, they do complicate the contest, particularly in those seats where there is no incumbent. Major party candidates in most inner metropolitan seats can never feel entirely relaxed when a high-profile Greens candidate enters the race.

Given that the Greens’ underlying primary vote is stable, even if not spectacular, it should be sufficient to ensure the Greens are returned as important players to the Senate.

Authors: Narelle Miragliotta, Senior Lecturer in Australian Politics, Monash University

Read more http://theconversation.com/greens-on-track-for-stability-rather-than-growth-this-election-116295