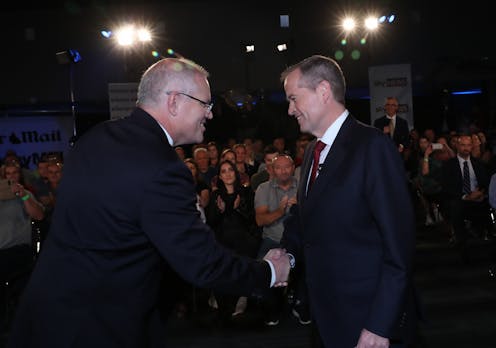

Up close and personal: Morrison and Shorten get punchy in the second leaders' debate. Our experts respond.

- Written by Rob Manwaring, Senior Lecturer, Politics and Public Policy, Flinders University

The best line of the second leaders’ debate between Scott Morrison and Bill Shorten wasn’t about policy, it was about … personal space.

Some in Queensland may have skipped the debate to watch the Friday night rugby, but they would have missed a pretty spirited clash between the Labor and Coalition leaders over everything from franking credits to religious freedom to even the closure of post offices across Australia.

Free to pace the stage and talk directly to voters in the “people’s forum” debate format in Brisbane, both Morrison and Shorten looked far more comfortable – and were certainly more confrontational – than in Monday’s more staid, conventional first debate in Perth.

Here’s what our academic experts thought.

Rob Manwaring, Senior Lecturer, Politics and Public Policy, Flinders University

When they are finally published, the no-doubt low viewing figures might well confirm that it is only a minority of committed political nerds whose idea of a great Friday night is to watch the leaders’ debate (albeit behind a TV paywall)!

Yet, once the debate got going, this was a strangely engrossing contest, covering a range of issues including religious freedom, post office closures, climate change, mental health, and inevitably, the economy.

What helped set up this oddly watchable debate was the first question on how the major parties will tackle high rates of sexual assault. It seemed to re-set the “mood”. There was a good degree of bipartisanship here, although a fault line did emerge over Labor’s commitment to introduce paid domestic violence leave.

This was a strong segment, perhaps reinforcing the best of what these debates can offer where political leaders are seeking to engage directly with the public concerns.

There were similarly compassionate discussions on other issues, especially about mental health and young people, as well as a question about support for veterans. Bill Shorten, on a number of occasions sought to engage people directly, perhaps most effectively asking the audience to indicate, with raised hands, if suicide and mental illness had impacted on their friends and family. Almost all hands went up.

On a lighter note, the debate itself had some decent jokes – for example, Scott Morrison amusingly allowing more time for Shorten to talk, as he “had more taxes to explain”. Later, as a questioner muddled their names, Shorten laughed off the claim that they looked the same.

An interesting flash point was during an increasingly heated exchange on income tax cuts for high-income earners when a fired-up Morrison moved to “stand over” and lecture Shorten. Shorten called out the PM as a “classic space invader”, and it had echoes of Mark Latham’s infamous encounter with John Howard in 2004, with the roles reversed.

Morrison tended to be better with numbers, Shorten stronger on key social policies and climate change. It was messy in places, but it was also considered, and there were clear policy and value differences at play. It was strangely watchable – much like Australian democracy.

Read more: Leaders try to dodge them. Voters aren't watching. So, are debates still relevant?

Alexandra Wake, Program Manager, Journalism, RMIT University

Even Sky News’ Peta Credlin effectively gave the second leaders’ debate to Bill Shorten, albeit through gritted teeth.

The Sky News panel agreed it was close, but by tackling issues like franking credits and negative gearing front on, Shorten came across as confident in Labor’s policy positions.

Both leaders did well, effortlessly using the campaign playbook to attempt to win over the 109 audience members chosen to attend by Galaxy Research. Shorten out-polled Scott Morrison as winner of the debate among audience members, but it was very close, just 43% to 41%. The rest were undecided.

There was a broad range of questions, most dedicated to familiar issues. But three questions were related to mental health in some way, and that appears to be the sleeper issue in this campaign.

A surprising question about the value of post offices in communities saw Shorten hint that an incoming government might use the country’s postal service as a possible competitor to the big banks.

Morrison, meanwhile, stuck to the Liberals’ core campaign message of better budget management and spending. He didn’t fluff his lines, but it’s not clear that his stock-standard responses will resonate with voters.

Shorten worked the room harder, and engaged the audience well by asking everyone who had been affected by suicide or mental illness to raise their hands. That’s an adept political tactic.

There were some light-hearted moments between the pair, but Shorten’s quip that Morrison was a “space invader”, as the taller PM came a little too close, might grab the headlines.

It’s easy to suggest the Twitterverse of political junkies hash-tagging #auspol with their sausage icon were also the real winners.

Scheduling the second leaders’ debate on Sky News in Brisbane at the same time as an NRL game – and in front of a Galaxy-selected audience – might have seemed like a stroke of PR lunacy.

But those Canberra-based commentators who scoffed at the terrible time and station for a debate clearly overlooked the fact Sky News is broadcast on WIN’s free-to-air network for regional Australia.

Morrison and Shorten were clearly tuned into 2018 Digital News Report Australia, which found that TV remains the main source of news for 36% of Australian news consumers – and it’s more popular in regional areas than metropolitan ones.

Read more: Morrison and Shorten take aim at one another in leaders' debate: experts respond

Mark Rolfe, Honorary Associate in Social Sciences, UNSW

For those who like sporting metaphors, this rumble in the jungle – well, a debate in Brisbane – showed that neither party leader is Muhammad Ali or George Foreman.

However, the “people’s forum” format made for a more free-flowing discussion that partially mitigated the leaders’ desire to control it and deliver prepared moves. Sure, they often returned to pet themes and slogans where they could. As such, we were presented with warnings of the danger of change and the failure to change, and both fought for the last word.

But both Scott Morrison and Bill Shorten were determined to emphasise civility and bipartisanship where they could. They wanted to appease the anti-politics sentiment and disillusion that abounds in Australia now, but also present differences in a palatable way to voters. Just like on Monday, Shorten got the better on these points with his queries to questioners and attempts to connect with their backgrounds.

They also had to demonstrate their spontaneity and knowledge when answering audience questions on important issues not usually highlighted in debates, such as domestic violence, sexual assault, mental health and veterans. In the process, the need to be flexible showed the personalities of both men, an important measure when there is still so much public suspicion of politicians.

With that, Shorten was more humorous, as demonstrated by his quip about Morrison being “a classic space invader” when he got too close.

And Shorten was prepared to directly demonstrate respectful disagreement with interrogators rather than avoid their questions, such as on the issue of freedom of religious expression. In this way, he aimed to present himself as not the usual politician but a man of substance.

Both leaders supplied substance with data and details of policies on issues such as profit-shifting, transfer pricing and taxing. Yet, both men were defensive on the vulnerabilities we’d expect: Morrison on climate and the Ruddock report on religious freedom; Shorten on franking credits and taxing multinationals.

Fortunately, they could avoid discussing the Labor and Liberals candidates who had walked the plank this week over imbecilic social media posts. But that is typical of a campaign so far absent the culture war battles of the past, although they still rumble below decks amongst some media.

Authors: Rob Manwaring, Senior Lecturer, Politics and Public Policy, Flinders University