Australia’s 2018 environmental scorecard: a dreadful year that demands action

- Written by Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

Environmental news is rarely good. But even by those low standards, 2018 was especially bad. That is the main conclusion from Australia’s Environment in 2018, the latest in an annual series of environmental condition reports, released today.

Every year, we analyse vast amounts of measurements from satellites and on-ground stations using algorithms and prediction models on a supercomputer. These volumes of data are turned into regional summary accounts that can be explored on our Australian Environment Explorer website. We interpret these data, along with other information from national and international reports, to assess how our environment is tracking.

A bad year

Whereas 2017 was already quite bad, 2018 saw many indicators dip even further into the red.

Temperatures went up again, rainfall declined further, and the destruction of vegetation and ecosystems by drought, fire and land clearing continued. Soil moisture, rivers and wetlands all declined, and vegetation growth was poor.

In short, our environment took a beating in 2018, and that was even before the oppressive heatwaves, bushfires and Darling River fish kills of January 2019.

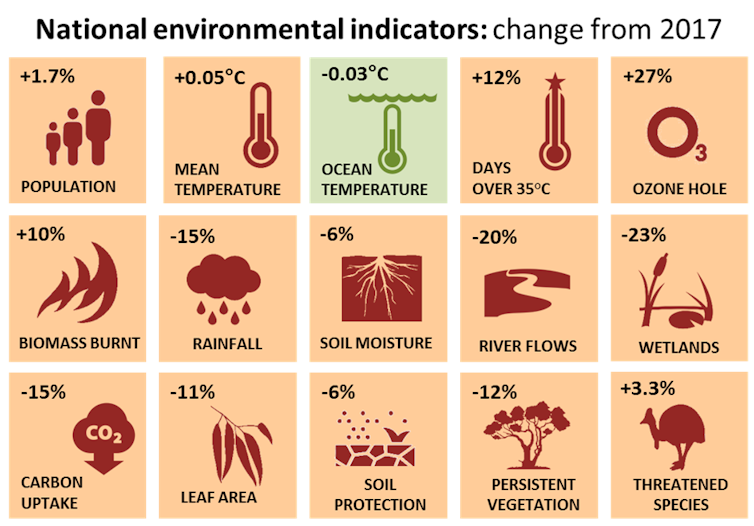

Indicators of Australia’s environment in 2018 compared with the previous year. Similar to national economic indicators, they provide a summary but also hide regional variations, complex interactions and long-term context.

source: http://www.ausenv.online/2018

Indicators of Australia’s environment in 2018 compared with the previous year. Similar to national economic indicators, they provide a summary but also hide regional variations, complex interactions and long-term context.

source: http://www.ausenv.online/2018

The combined pressures from habitat destruction, climate change, and invasive pests and diseases are taking their toll on our unique plants and animals. Another 54 species were added to the official list of threatened species, which now stands at 1,775. That is 47% more than 18 years ago and puts Australia among the world’s worst performers in biodiversity protection. On the upside, the number of predator-proof islands or fenced-off reserves in Australia reached 188 in 2018, covering close to 2,500 square kilometres. They offer good prospects of saving at least 13 mammal species from extinction.

Globally, the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere accelerated again after slowing down in 2017. Global air and ocean temperatures remained high, sea levels increased further, and even the ozone hole grew again, after shrinking during the previous two years.

Sea surface temperatures around Australia did not increase in 2018, but they nevertheless were well above long-term averages. Surveys of the Great Barrier Reef showed further declining health across the entire reef. An exceptional heatwave in late 2018 in Far North Queensland raised fears for yet another bout of coral bleaching, but this was averted when sudden massive downpours cooled surface waters.

The hot conditions did cause much damage to wildlife and vegetation, however, with spectacled flying foxes dropping dead from trees and fire ravaging what was once a tropical rainforest.

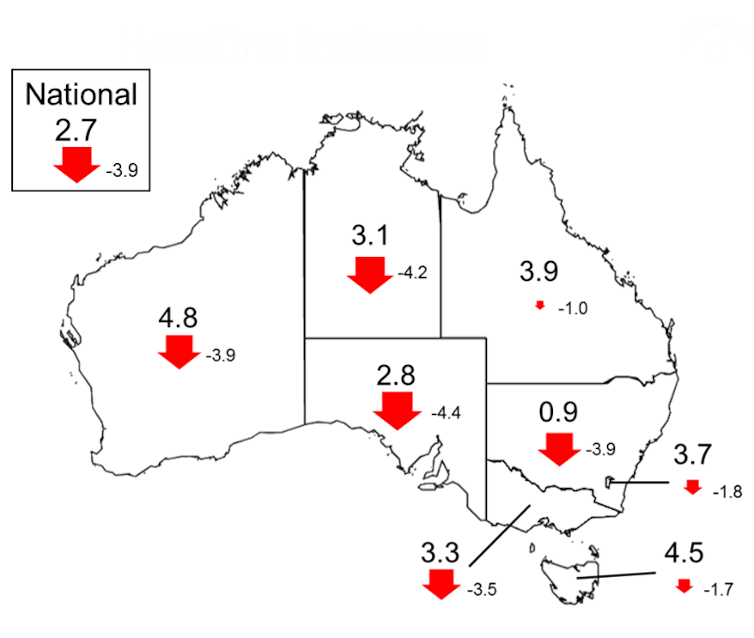

While previous environmental scorecards showed a mixed bag of regional impacts, 2018 was a poor year in all states and territories. Particularly badly hit was New South Wales, where after a second year of very poor rainfall, ecosystems and communities reached crisis point. Least affected was southern Western Australia, which enjoyed relatively cool and wet conditions.

Environmental Condition Score in 2018 by state and territory, based on a combination of seven indicators. The large number is the score for 2017, the smaller number the change from the previous year.

source: http://www.ausenv.online/2018

Environmental Condition Score in 2018 by state and territory, based on a combination of seven indicators. The large number is the score for 2017, the smaller number the change from the previous year.

source: http://www.ausenv.online/2018

It was a poor year for nature and farmers alike, with growing conditions in grazing, irrigated agriculture and dryland cropping each declining by 17-20% at a national scale. The only upside was improved cropping conditions in WA, which mitigated the 34% decline elsewhere.

A bad start to 2019

Although it is too early for a full picture, the first months of 2019 continued as badly as 2018 ended. The 2018-19 summer broke heat records across the country by large margins, bushfires raged through Tasmania’s forests, and a sudden turn in the hot weather killed scores of fish in the Darling River. The monsoon in northern Australia did not come until late January, the latest in decades, but then dumped a huge amount of rain on northern Queensland, flooding vast swathes of land.

Read more: The Darling River is simply not supposed to dry out, even in drought

It would be comforting to believe that our environment merely waxes and wanes with rainfall, and is resilient to yearly variations. To some extent, this is true. The current year may still turn wet and improve conditions, although a developing El Niño makes this less likely.

However, while we are good at acknowledging rapid changes, we are terrible at recognising slow, long-term ones. Underlying the yearly variations in weather is an unmistakable pattern of environmental decline that threatens our future.

New South Wales was hit hard by drought in 2018.

AAP Image/Perry Duffin

New South Wales was hit hard by drought in 2018.

AAP Image/Perry Duffin

What can we do about it?

Global warming is already with us, and strong action is required to avoid an even more dire future of rolling heatwaves and year-round bushfires. But while global climate change requires global action, there is a lot we can and have to do ourselves.

Read more: Australia is not on track to reach 2030 Paris target (but the potential is there)

Australia is one of the world’s most wasteful societies, and there are many opportunities to clean up our act. Achieving progress is not hard, and despite shrill protests from vested interests and the ideologically blind, taking action will not take away our prosperity. Home solar systems and more efficient transport can in fact save money. Our country has huge opportunities for renewable energy, which can potentially create thousands of jobs. Together, we can indeed reduce emissions “in a canter” – all it takes is some clear national leadership.

The ongoing destruction of natural vegetation is as damaging as it is unnecessary, and stopping it will bring a raft of benefits. Our rivers and wetlands are more than just a source of cheap irrigation for big businesses. With more effort, we can save many species from extinction. Our farmers play a vital role in caring for our country, and we need to support them better in doing so.

Our environment is our life support. It provides us our place to live, our food, health, livelihoods, culture and identity. To protect it is to protect ourselves.

This article was coauthored by Shoshana Rapley, an ANU honours student and research assistant in the Fenner School of Environment and Society.

Authors: Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University