Growing Up African in Australia: racism, resilience and the right to belong

- Written by Kathomi Gatwiri, Lecturer, Southern Cross University

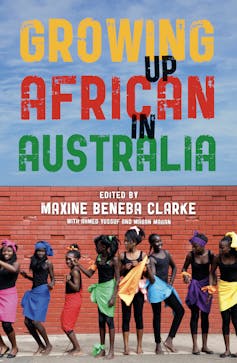

Review: Growing Up African in Australia, edited by Maxine Beneba Clarke, Magan Magan and Ahmed Yussuf

For many African-diaspora people in Australia, belonging means masking yourself. To fit in is to curate one’s Africanness and one’s blackness. You teach yourself to see-saw between the splitting identities of who Australia needs you to be, and who you really are. You just never simply are.

A new collection of writing curated by Australian writer Maxine Beneba Clarke explores this state of conditional belonging. This is the latest in a series of “Growing Up” anthologies published by Black Inc.

Clarke, with the assistance of Ahmed Yussuf and Magan Magan, has put together a nuanced collection that illustrates the diversity of Africanness and how it is experienced here.

A new collection explores the experiences of African-diaspora people in Australia.

Black Inc

A new collection explores the experiences of African-diaspora people in Australia.

Black Inc

In her introduction, Clarke highlights the perverseness of the slave trade and the insidiousness of colonialism, upsetting the dominant perception that Africans only arrived in Australia recently. They did not. The first recorded African-diaspora settlers were convicts who landed with the First Fleet in 1788. They were 11 in number and quite involved in the colonial project of displacing Aboriginal people from their land. That’s where the conversation begins – as it should.

The phrase African-diaspora people is deliberately used instead of “Africans”, to include people of Afro descent who do not necessary “come from” Africa. From Brazil, to Guyana to Jamaica, Africa ceases to be a geographical space and becomes an embodied experience.

People of Afro-descent live everywhere across the globe and carry different histories, belief systems and ideological convictions. What often unites them in Australia, as the book establishes, is the singularity with which they are classed. “The Africans”.

Growing Up African is divided into six sections, but there are clear themes throughout: displacement, isolation, racism, resilience, survival, and the fight for the right – or privilege – to call Australia home.

Read more: Speaking with: Author Anita Heiss on Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia

In the first section, contributors explore their “roots” and their childhoods in Australian backyards and playgrounds. They share memories of establishing connection with the new country and the longing for the other home – the one they left behind.

Many reflect on the joy and gratitude they felt upon their arrival in Australia. Others explore the extent to which meaningless wars and conflict ripped their lives apart, forcing them to abandon homes, friends and families – and the resulting trauma, grief and loss. Nyadol Nyuon, an industrial lawyer in Melbourne, writes:

The shameless indifference of war means that families become strangers. War reduces the most intimate relationships to meaningless connections […] [it] not only separated me from my grandmother; I was also separated from my mother and knew little of my father. I grew up with fragments of who they are, the broken links of kinships.

Nyadol Nyuon writes about the impact of war in Growing Up African in Australia.

Black Inc

Nyadol Nyuon writes about the impact of war in Growing Up African in Australia.

Black Inc

Relationships with the new country are complicated not only by the shock of the newness of a different space, but also by Australia’s history. It is within this colonial context that the Afro-Blackness of African-diaspora Australians is made visible. Here they begin to feel, or are told, that their blackness is a marker of something – something less desirable.

The contours of racism

The book’s most dominant theme is racism – both overt and covert – and how it punctuates the lives of black people living in Australia. Historically, and still today, skin colour has been a marker of difference and a gauge of otherness here.

Heartbreaking stories detail how the African body is layered with suspicion of criminality, inferiority and inadequacy. In the white Australian space, the black African body struggles to be viewed as worthy or deserving. It is deviant.

Read more: Sudanese heritage youth in Australia are frequently maligned by fear-mongering and racism

Stories in this book amplify what Virginia Mapedzahama and Kwame na Kwansah-Aidoo argue elsewhere: that blackness is not only defined and constructed through the lens of whiteness, “it is also inferiorised by it”.

Jafri Katagar Alexander reflects on his experiences as a black African male living in Melbourne:

Some landlords and real estate agents are prejudiced, and they won’t rent or sell their houses to black people. […] When I go out to the shops to buy something, they look at me as if I am going to steal something […] When you are black, you are easily stopped and searched by some police officers […] I have many times been called a “black dog”, “black cat”, “nigger” and so on. I have also been told, “Go back to Africa” […] I have been attacked and pepper-sprayed by the police.

Racism as experienced by African-diaspora people in Australia is not just seen and heard, it is also felt. It is rampant and obvious for those who experience it, but silenced and denied by those who perpetrate it. It is being watched constantly with suspicion.

Manal Younus writes, “I’d hear, ‘you are too dark’, such simple words enough to spark a disdain for this blackness.” Eventually, due to the assault of racism on people’s sense of self, many learn to carry their blackness as a burden.

Read more: The politics of black hair: an Australian perspective

Where are you (really) from?

Belonging is not a given. It is constantly challenged. The question “where are you from?”, while seemingly innocent, symbolically deports African-diaspora people back to faraway places. This question particularly confronts those who have no other place to call home.

While Australians of African descent may live in Australia as law-abiding and productive citizens, the ongoing scrutiny, questioning and unending construction of foreigner status positions them as “perpetual strangers”. Nyuon articulates this in the book, writing about her younger siblings:

I wonder what it would feel like to feel Australian but happen to be black […] How do you hold on to a sense of belonging when it is so often assaulted by racism?

Belonging is further complicated by the process of racialisation – when a particular racial identity is imposed on an individual or a group, without their consent. Recognising the hyper-visibility of their skin colour, the authors reflect on the difficult and transcendental journeys of embracing their blackness, resenting it, or feeling separated from it.

Poet and author Maxine Beneba Clarke has curated this collection of stories about the experiences of African-diaspora Australians.

Black Inc

Poet and author Maxine Beneba Clarke has curated this collection of stories about the experiences of African-diaspora Australians.

Black Inc

This journey can be liberating, but it can also foster a deep sense of exclusion, knowing that to be fully human in Australia, and to exist with dignity, is to be white. Therefore to be non-white, particularly to be black, is occupy the space on the margin. It is to not belong. To this end, Nyuon asks:

Was home something you embraced or did it also have to embrace you back? Would I always be seen as a conditional citizen, to whom citizenship was not a right, but a gift that could only be kept by an impeccable character? […] Should I consider a back-up plan - go back to where I came from? Where was home?

But still like air … they rise

In the face of structural barriers to health care, education, housing and employment, the narratives in Growing Up African are tempered with stories of deep courage, hope, resilience and endurance.

Despite the ever-lingering knowledge of “their place” in Australia, African-diaspora peoples continue to make an enormous contribution to this place they now call home, in academia, finance, social work, health care, engineering, business, digital media, law, and politics.

One thing remains clear (but still unspoken) in this book. Marginalisation breeds resentment, mental illness, violence and a deep sense of internalised powerlessness. It chips away at people’s humanity.

African-diaspora Australians have much to contribute to the country that has so generously opened its doors to them, but they can only do so to the extent that they are “allowed” to belong. Belonging means thriving. It means home.

Authors: Kathomi Gatwiri, Lecturer, Southern Cross University