voices from the bush – how lockdown affects remote Indigenous communities differently

- Written by Claire Smith, Professor of Archaeology, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University

What does self-isolation mean when you live in one of Australia’s most remote Aboriginal communities? What does social distancing mean when the average household holds 12-15 people? How do you think through viral vulnerability when people in your community already die too young and too frequently?

These are just a few of the questions that might be asked of Aboriginal people living in remote parts of Australia as the COVID-19 pandemic swirls around them and other Aboriginal communities across the nation.

We work with the communities of Barunga, Beswick, Manyallaluk and Borroloola in the Northern Territory. We have worked with the same communities for up to 30 years. We have recorded many changes through time and come to learn something about life in remote communities from Aboriginal people. We have learnt from elders, mid and younger generations.

Our new research comes from regular phone conversations with community members about the impact of COVID-19. These phone calls bridge the remote and urban divide, as we discuss what is known about the virus and how long before things get back to normal. By sharing the experiences of Aboriginal families who live in remote NT communities, more voices will find a place in the national conversation.

Safe in the bush

Aboriginal people have talked about feeling safe out bush, about following the rules of lockdown. Locals like Garrwa/Waanyi woman and Borroloola resident Gloria Friday praise their communities for “abiding by the rules, not running around, keeping an eye out and being really careful”. They are fully aware of the threat COVID-19 poses to their old people and those who are sick.

At a time when travel to and from these communities is prohibited, contact with the outside world is important. Barunga Elder and Junggayi (custodian) Narritj, says:

Phone call. You on that side, us on this side. We need that, too. We want to know what is happening in other places. We want to know the truth about that virus. (April 30 2020)

For people living in Borroloola, the spread of information has been rapid. As Gloria Friday explains:

Everyone with TV knows what’s going on. And I listen to news all the time, I’ve got a little radio and I listen to the news about the virus and what’s going on in the world.

Read more: Urban Aboriginal people face unique challenges in the fight against coronavirus

Official health messaging for Indigenous communities.

Dept of Health

Official health messaging for Indigenous communities.

Dept of Health

Vulnerable communities, new babies

Humans are vulnerable to disease for many reasons including age, gender, society, environment and ancestry. We know the COVID-19 risks are magnified for Aboriginal people in remote communities.

This is due to higher rates of other health issues, limited access to health care, greater reliance on outreach services and movement between communities.

The COVID-19 situation has brought specific health challenges to Aboriginal women in remote areas. For years it has been common for women to leave their communities to give birth in regional or major hospitals. This can bring sadness and a sense of dislocation from family, country and ceremony.

Because of COVID-19 lockdowns, women and their newborns are away longer from family and culture. They have to be quarantined before returning to country. An alternative approach is to restrict the mother’s movements when she is away from home. Bangirn, a young woman from Barunga who recently gave birth in Darwin, says:

I couldn’t go anywhere when in Darwin because I have recently had a baby. I wasn’t allowed to go out shopping to buy baby clothes or things for the baby. The doctors rushed me into Katherine hospital but I wasn’t allowed to go and buy baby things. My sister had to give me her daughter’s baby old clothes over the fence. Doctors gave me a paper saying that I didn’t go anywhere while in Darwin and Katherine. The paper shows that me and my partner could go back in the community. I couldn’t do food shopping while leaving Katherine or baby clothes. Barunga store hasn’t got anything for the baby. (May 5 2020)

It’s hard. Right now she’s got no warm clothes and this weather is cold. We’re keeping her warm with a big blanket. We’re safe but it’s hard, really hard. (May 11 2020)

We hope to understand these experiences and how they shape families, culture and connections into the future. This can help us to plan for any future pandemics and its impact on Indigenous communities.

Recognition of vulnerability for remote Aboriginal communities prompted fast action by Australian governments, research and information networks and Aboriginal organisations. In addition to regional lockdowns there was a multi-million dollar information campaign.

This included YouTube videos in many different Aboriginal languages by the NT government and a video series in 18 languages by the Northern Land Council.

The COVID-19 crisis adds to existing pressures on remote communities. Families already live with regular loss of life, frequent funerals and an overhanging grief that contributes to intergenerational trauma. Yet among these hardships communities also display incredible resilience. While COVID-19 poses a threat, this needs to be understood in relation to the hardships and the strengths of remote community life.

Read more: Coronavirus will devastate Aboriginal communities if we don't act now

Responses to being ‘locked up’

Little attention has been paid to the lived experience of social distancing across cultures. We need to understand how different peoples think about social distancing and isolation. For Graham and Gloria Friday, the best strategy for social distancing is “going out bush”, rather than staying in your house … because country is home.

If you out bush, you might find that bush medicine to fight it. Also out bush, you don’t have to worry about food in the shops, you can live off your land, fish, dugong, turtle, goanna, you can live off that. (April 9 2020)

Similarly in Barunga, one community member says their first response to being “locked up” was to go out bush and sit down on country. Anne Marie Lee, chair of the board of the Sunrise Health Service Aboriginal Corporation says:

More people are going out camping and fishing. People spend maybe a week out there. It’s a really good thing, eating that bush tucker again. People are looking more healthy. (May 11 2020)

Going bush can be an opportunity to learn new skills. Adam Macale, aged 15 from Manyallaluk, caught these fish.

Rachael Kendino, Author provided (No reuse)

Going bush can be an opportunity to learn new skills. Adam Macale, aged 15 from Manyallaluk, caught these fish.

Rachael Kendino, Author provided (No reuse)

Going bush has had the added effect of strengthening families. As people hunt and fish, they are away from the worries of town. They are well fed and access to alcohol is limited. Young people learn traditional survival skills. The health and well-being effects of being out bush are part of long-standing and culturally defined preventative health-care strategies.

Some aspects of Aboriginal people’s experiences of lockdown are familiar to all Australians: the importance of socialising with extended family for mental and emotional well-being. Also, people seem to be more conscious of their health. Some community medical clinics report an influx of people getting flu vaccinations.

Yet another factor that shapes the COVID-19 experience for Aboriginal people in remote areas is the historical experience of being “locked up” on missions and in prison.

The NT has the highest imprisonment rate of any state or territory. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders comprise 84% (1,477 prisoners) of the adult prisoner population. In 2018, the national average was 28%. Families in Borroloola have called for people to be returned home during the pandemic to ensure they are safe and away from the threat of virus infection in prison. The investment in family and making sure everyone is safe has been a driving focus for many in these communities.

Some good things, too

Perhaps unexpectedly, there have been some positives from the COVID-19 crisis.

One of the first actions was for states and territories to nominate designated biosecurity areas. Travel to these areas was restricted to essential workers. Returning community members have to go into quarantine. This shutdown was sudden but it made some community members feel reassured. Beswick Traditional Owner, Esther Bulumbara says:

Suddenly everything stopped. It was a great shock to the Northern Territory. We thought only that overseas mob would get that. But police said everything had to close. Government mob, shire. It was lucky it was quick. If they didn’t know about it, it would have gone through the Northern Territory. (April 24 2020)

The lockdown bolstered trust in government and Aboriginal organisations. Graham Friday is among those “talking with all those big mob government officials” as community in Borroloola are consulted about when and how things might open up again.

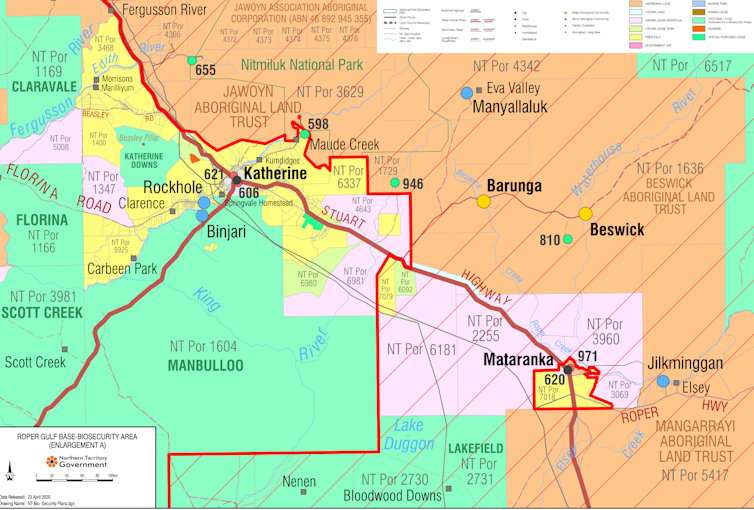

Designated biosecurity areas near Katherine, Northern Territory.

NT Govt.

Designated biosecurity areas near Katherine, Northern Territory.

NT Govt.

People feel safe because their exposure to COVID-19 has been controlled. Reflecting on the situation in Borroloola, Gloria Friday says:

It’s amazing cause the virus never hit the community yet or nothing, and it was good because everyone was abiding by the rules. And because they limited the grog sale to six can, six can a day, everything was quiet and there’s been no problems in the town, everyone’s just been go out fishing and hunting. It’s been good. (May 1 2020).

In some cases, COVID-19 has deepened relationships between Aboriginal people and the wider community. There has been unanticipated support. In the Katherine East region, large quantities of clothing were donated by Rockmans. Boxes of food were donated by Coles. Outback Stores issued food vouchers. Community members were surprised and pleased, reports Esther Bulumbara. She says:

Fiona from AIG donated all the boxes of clothes to Barunga and Beswick and Manyallaluk. It made people feel good. All the ladies they all came and got some clothes. Long sleeved shirts, woolly jumpers and coats. All new. And we got that Mob’s Choice in Bagala Store at Barunga now. Low prices, like at Woolies. (May 14 2020)

Rachael Kendino of Manyallaluk adds:

Every house at Manyallaluk got two boxes of food and a $50 voucher from Beswick store […] I like what the Roper Gulf Shire are doing. They pick up [people] every Thursday for shopping from Manyallaluk to Barunga store. Before we had to get taxi to go to Katherine to buy food […] Going in and return is $300 each way. She told me about online shopping, too. (May 8 2020)

Food vouchers from Beswick Community Store.

Rachael Kendino

Food vouchers from Beswick Community Store.

Rachael Kendino

People are appreciative of the efforts made by local police to keep them safe and connected. The mail is taken 50 kilometres to the Central Arnhem Highway turn-off. It is handed over to police and taken to Maranboy police station, 10 kilometres from Barunga. A community representative comes to the police station to collect it. The letters are wiped down. Jessala McCale of Barunga reports:

Police officers must make sure that letters, mails are clean before handing it over the person who handles the mail. (May 5 2020)

Jawoyn Elder Jocelyn McCartney says:

The policeman are camping out there at the Barunga turnoff. Turn and turn. All day and all night. To make sure people don’t come out of community. People not allowed to come into our community because they might have that virus. (May 12 2020)

Getting the right information

Elsewhere in the world it has been noted “living without broadband has gone from a mild inconvenience to a near impossibility”. For remote communities, the problem can be how to get information on a global pandemic without internet.

Crisis communication must be tailored to different needs and in many forms. While Indigenous youth are savvy with social media, many older people watch television or listen to the radio to get information. Our community contacts spoke about President Trump and laboratories in Wuhan. Like all of us, Aboriginal people judge leaders and feel sadness for those who have died. As one community member made clear:

He’s a real mongrel that Trump, he just sits there while those bodies all pile up. (May 1 2020)

Aboriginal people in remote communities are well aware of what is happening across the world. The sense this problem is big and concerns all of us is not lost on them. Another community member from Borroloola reveals:

I’ve got family all round – Doomadgee, Normanton, Mt Isa, Townsville, Borroloola – and we really worry for all of them. We all worry about each other and ring each other all the time. All of them, everybody is quarantined all over the world, from Burketown, Mt Isa, Mornington Island, Italy, even America … the lot. (May 1 2020)

White man’s disease

Remote communities are not all the same. While many challenges are shared, each community has its own history and culture which shapes the present. Our preliminary research suggests COVID-19 messages are understood slightly differently across communities.

In some communities, reports from Italy and Spain seem very distant and of little relevance. In others, Aboriginal people of all ages watch television and trawl social media, sad for the “poor Italians” and “bodies piling up in the United States”.

Some talk about COVID-19 as a “white man’s disease”. Others, such as Graham Friday and members of his family (Gloria Friday and Adrianne Friday), see it as “everybody’s problem and everybody’s responsibility”.

One shared factor has been the pressure of acute food shortages in community stores. In the early days, some people responded by breaking quarantine restrictions to access local towns via back roads and dirt tracks. This placed their community at increased risk. The community and police responded in tandem. A Barunga community member says:

A couple of young boys tried to go into town. The policeman came and warned them. They going to get a fine. I told that boy ‘You got to stop that. No more. I can’t pay that fine for you’. (April 24 2020)

Police also set out clear social distancing expectation in Borroloola, as Gloria Friday explains:

Well the police only went and said they didn’t want to see no gambling, like ten people only in one place. But in the community they’re bored, they got nothing to do. Policeman went and told them once, and I think everybody listened. (May 1 2020).

A bullet dodged

At this time, Aboriginal people in the NT seem to have dodged a bullet. This is because swift and culturally appropriate action was taken by governments, Aboriginal organisations and communities themselves. The Northern Land Council and the Central Land Council, in particular, provided outstanding coordinated leadership in the fight against COVID-19.

There is a lesson for Australia’s efforts to Close the Gap: trusted Aboriginal leadership is essential to successful outcomes for Aboriginal communities.

COVID-19 is the first global pandemic caused by a coronavirus. It may not be the last. This crisis presents a unique opportunity to learn what success looks like in Aboriginal remote community health.

The United Nations has called for all member states to include the specific needs and priorities of Indigenous peoples in COVID-19 response planning. Population-based approaches are logical scientific steps to prevent the spread of a virus. However, they need to be compatible with the everyday cultural lifeways of remote Aboriginal communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a watershed moment. Old and enduring problems can be reassessed. The current crisis can be mined for fresh, action-oriented perspectives of Aboriginal people’s needs in preventative health care. This time of calamitous infection and threat of illness is not foreign to remote Aboriginal communities and culture bearers. Many have lived through previous flu epidemics and live with the scourge of chronic conditions.

While COVID-19 is presented as a health and an economic problem, it is also a social and a cultural challenge. Our research calls for attention to understanding Aboriginal people’s knowledge of the pandemic and their vulnerability and strengths at this time. Remote communities are full of intellectuals and people coming to terms with a challenge we all face. Yet they are making sense of this global crisis in their own local and culturally nuanced ways.

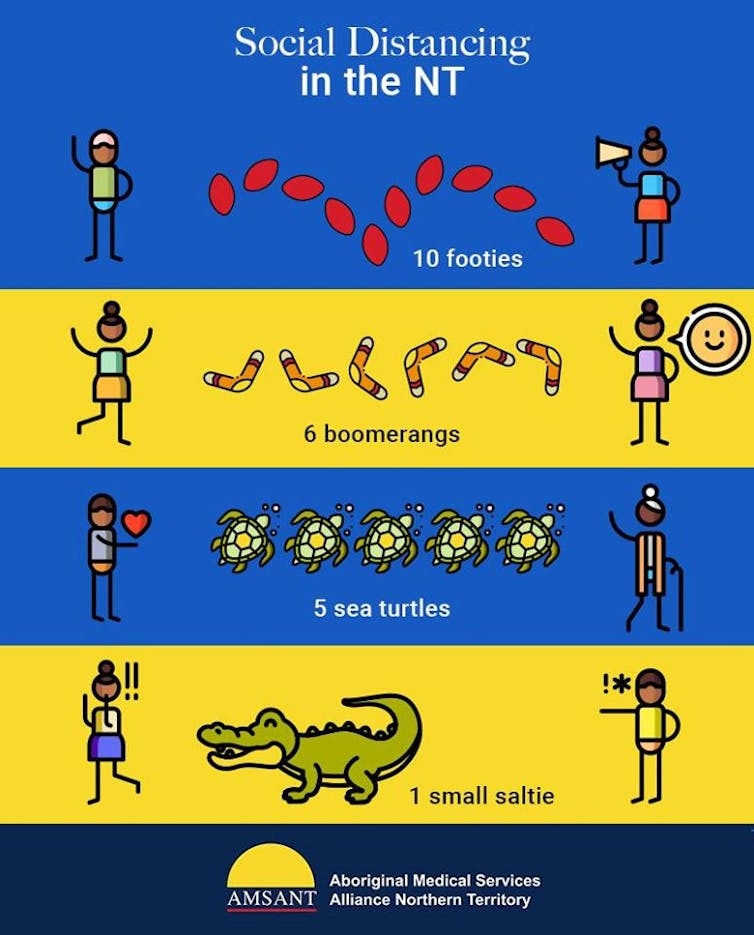

Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory, CC BY

While we have focused on remote communities, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are at risk.

Community wisdom and cultural strengths are powerful starting points for effective and empowering health promotion. We need to identify local innovations and community solutions for dealing with COVID-19, and harness their drivers and logic. We need to develop culturally-driven, community-specific tools and strategies that can help protect Aboriginal communities from pandemics and provide lasting benefits.

Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory, CC BY

While we have focused on remote communities, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are at risk.

Community wisdom and cultural strengths are powerful starting points for effective and empowering health promotion. We need to identify local innovations and community solutions for dealing with COVID-19, and harness their drivers and logic. We need to develop culturally-driven, community-specific tools and strategies that can help protect Aboriginal communities from pandemics and provide lasting benefits.

Authors: Claire Smith, Professor of Archaeology, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University