Mavis Ngallametta review - a bittersweet collection of a songwoman's stories of home

- Written by Chari Larsson, Lecturer of art history, Griffith University

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains references to deceased people.

This has been a difficult review to write. The late Aurukun artist Mavis Ngallametta’s major survey exhibition Show Me the Way to Go Home opened in March at the Queensland Art Gallery. I was lucky enough to view the exhibition before QAG shut its doors to the public a couple of days later.

Now the gallery has uploaded a video journey through the exhibition with co-curator Katina Davidson. But my concern is the exhibition will be another victim of COVID-19, through no fault of its own. Perhaps future historians will look back on the earliest days of the pandemic and ask what fell through the cracks? What were the unseeable exhibitions? Writing these words somehow feels like writing a love letter to the future.

This exhibition is both important and necessary, securing Ngallametta’s rightful position in Australian art history.

Songwoman

Mavis Ngallametta was a Kugu woman born near the Kendall River in west Cape York Peninsula. She lived a traditional life on Country until she was five, when her family moved to the Presbyterian Mission further north at Aurukun. Ngallametta later became an elder of the Putch clan, and a cultural leader of Aurukun’s Wik and Kugu people.

She was a songwoman and the exhibition’s title is drawn from Irving King’s 1925 Show Me the Way to Go Home, one of Ngallametta’s favourite songs.

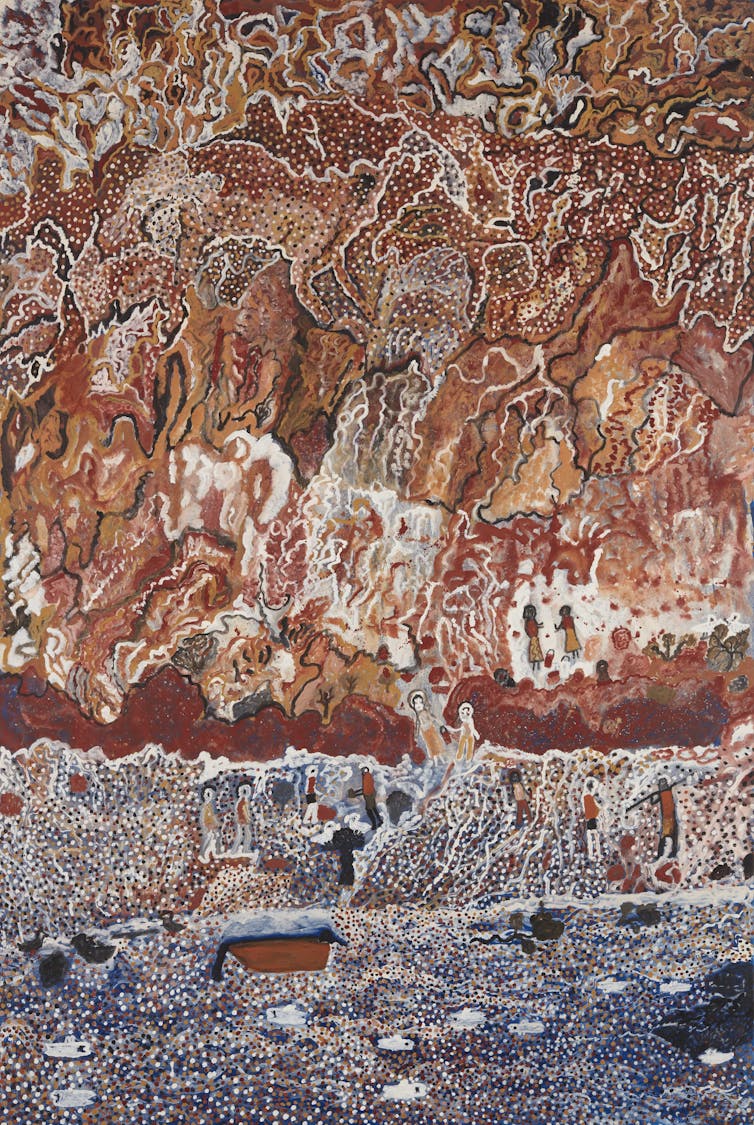

Mavis Ngallametta’s Ikalath #9 2013 from the Janet Holmes à Court Collection.

Photo: Gina Allain

Mavis Ngallametta’s Ikalath #9 2013 from the Janet Holmes à Court Collection.

Photo: Gina Allain

More than 40 of Ngallametta’s paintings and sculptures are assembled for the first time. The exhibition is organised in terms of site, or groupings of paintings that are records of the most significant places in her life. The Kendall River series for instance, was inspired by a 2013 helicopter trip, where Ngallametta and a number of her family returned to their Country.

What comes to the fore is just how rapidly Ngallametta’s command of the medium took place. Ngallametta was introduced to acrylic paint at a women’s painting workshop at the Wik and Kugu Art Centre in 2008 at the age of 64. From 2010, her works started to grow in scale and ambition. It was also around this time that Ngallametta shifted away from acrylics to ochres and clay.

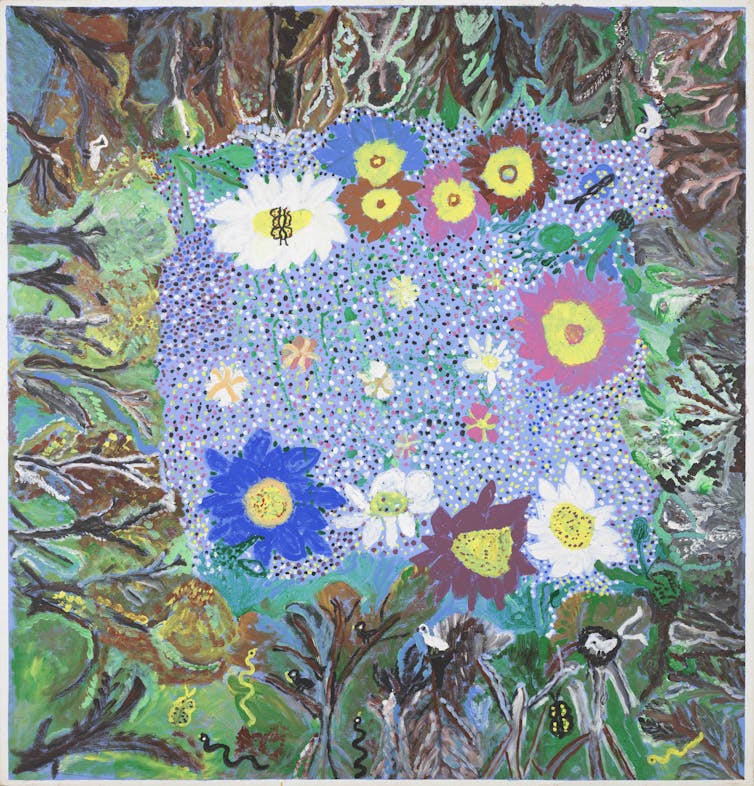

Kugu-Muminh people, Putch clan Australia QLD 1944-2019 Pamp (Swamp) 2009. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery.

Photo: Natasha Harth

Kugu-Muminh people, Putch clan Australia QLD 1944-2019 Pamp (Swamp) 2009. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery.

Photo: Natasha Harth

Connections to the land

Inscribed on the paintings’ surfaces is the complexity of Ngallametta’s connection to the land in and around Aurukun. Ikalath, the coastal region north of Aurukun, has spectacular red cliffs that rise steeply from the sandy beaches. The cliffs are where sacred white ochre is collected for paint. As a Kugu woman, this was not Ngallametta’s traditional country. It was through her adopted son Edgar’s blood ties that she inherited a relationship to Ikalath.

In a remarkably short period of time, Ngallametta developed her own distinct visual language, drawing from tradition and punctuated with her own unique motifs. The waterlilies and birds that featured in her early acrylics never fully disappear from her later works. Ngallametta would start with an acrylic blue base and gradually build the layers of paint from there. The blue unifies her practice, as well as reflecting the ebb and flow of the ocean, swamps and waterways she was responding to.

Read more: Mavis Ngallametta is causing a quiet stampede in the art market

The meandering lines are interspaced with dots, as well as delightful nods to realism such as flowers, ducks and pigs. Her paintings draw close to oral story telling techniques, where she conveys an intimate knowledge of the land, combined with personal details and memories: family camping trips, fishing and preparing painting materials.

Before turning her attention to painting, Ngallametta was a master weaver, using materials such as cabbage palm and pandanus. Later, she would weave from ghost nets, or discarded fishing nets that washed up as detritus on the beaches of Queensland’s far north.

Ik (Basket) 2010. Collection of The University of Queensland.

Photo: Carl Warner

Ik (Basket) 2010. Collection of The University of Queensland.

Photo: Carl Warner

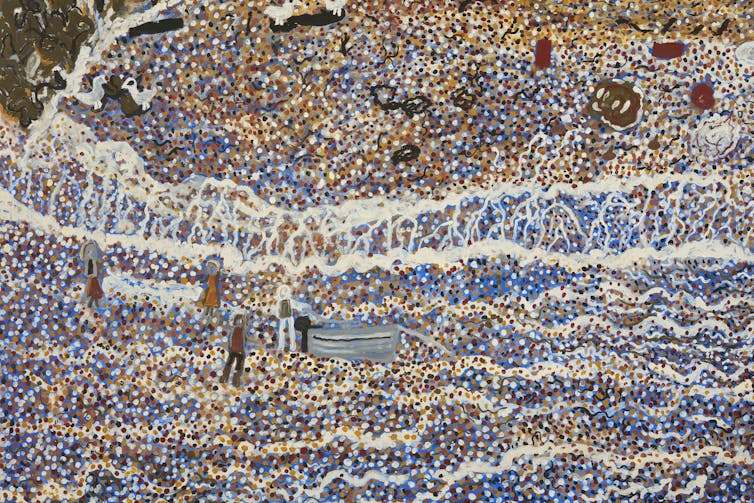

The influence of Ngallametta’s weaving practice is evident through this exhbition. The strong horizontal bands that feature on her ghost net baskets reappear on her canvases as an intricate weft and weave of colour and paint.

Dragging Net at Less Creek (detail) 2015. Collection: Johnny Kahlbetzer, Sydney.

Photo: Jenni Carter

Dragging Net at Less Creek (detail) 2015. Collection: Johnny Kahlbetzer, Sydney.

Photo: Jenni Carter

Bird’s eye

There are many ways the history of Australian landscape painting can be written. One possible genealogy is via artists’ attempts to resolve the vastness and enormity of the country. William Robinson’s swirling landscapes with multiple points of perspective are logical points of comparison. However, Ngallametta, is doing something very different from Robinson.

The use of bird’s or mind’s eye perspective is a familiar technique used by Indigenous artists to represent country. Ngallametta evokes the sensation of flying over the land, only to have the land fold back and over, enveloping the viewer.

In this way, standing in front of Ngallametta’s enormous paintings is akin to the experience of standing before a giant wave. Her paintings rise up, asserting their physical verticality and threatening to engulf the viewer. This vertiginous experience is counteracted by the strong horizontal bands. These anchor the viewer, creating not just one, but many possible horizons. The horizontal and vertical are in constant dialogue, creating a tension that pulses with the energy of life in Queensland’s far north.

Joyful and exuberant, with accents of wry humour, Mavis Ngallametta’s paintings, weavings and sculptures are exactly what we all need right now. Hopefully we will get to see them in person again soon.

Burdekin ducks 2011. Dux of Distinction Collection: John Conroy.

Photo: Carl Warner

Burdekin ducks 2011. Dux of Distinction Collection: John Conroy.

Photo: Carl Warner

Although the Queensland Arts Gallery is currently closed, Show Me the Way to Go Home is scheduled to continue until 2 August 2020. A series of exhibition videos can be viewed [here].

Authors: Chari Larsson, Lecturer of art history, Griffith University