This coronavirus share market crash is unlike those that have gone before it

- Written by Kylie-Anne Richards, Lecturer, Finance Discipline, University of Technology Sydney

Stock markets have crashed, we can be confident of that. History suggests there is no quick recovery from crashes like these, which means lasting consequences for investors.

The World Health Organisation declared the COVID-19 coronavirus a pandemic last Wednesday, wiping US$7 trillion off global equity markets. A day later, now marked down in history as Black Thursday, the Dow Jones index in the US closed down 2,353 points (-10%), the worst single day points decline since Black Monday in 1987.

Staggeringly, the index rebounded sharply the following day. Friday saw the US market closing the roller coaster week up 9.3%.

Shares in the Australian S&P 200 index did the same sort of thing.

Prices collapsed 8% after opening Friday, then rebounded throughout the day to end up about where they started, before collapsing 9.5% on Monday.

Not even normal for a crash

The volatility, velocity and magnitude of these swings is not in the playbook of past global market crises.

Generally, markets have been overvalued, with stocks climbing sharply in recent years despite tepid economic growth in the US and elsewhere and heightened economic and political uncertainty.

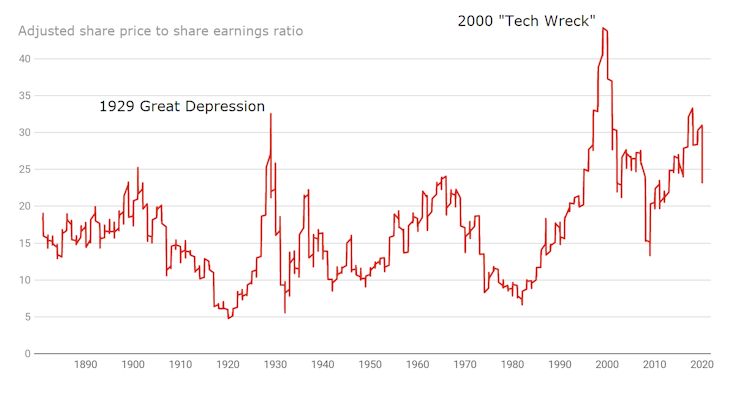

If we look at Nobel Prize winner Robert Shiller’s cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio, a standard equity valuation metric, there have been only two other times in modern history when the US stock market has been more overvalued than today.

They were in 1929 and 2000; ahead of the Great Depression and, more recently the 2000 “Tech Wreck”.

Shiller total return cyclically-adjusted price-earnings ratio

The data and CAPE Ratio used to create this graph were developed by Robert J. Shiller using various public sources. Neither Robert J. Shiller nor any affiliates or consultants, are registered investment advisers and do not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the CAPE Ratio here, or any data or methodology either included therein or upon which it is based.

The data and CAPE Ratio used to create this graph were developed by Robert J. Shiller using various public sources. Neither Robert J. Shiller nor any affiliates or consultants, are registered investment advisers and do not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the CAPE Ratio here, or any data or methodology either included therein or upon which it is based.

What has been so interesting about the bubble that preceded the coronavirus crash is that there was no identifiable underlying economic or social process driving the market to such dizzying heights.

But there was ultra-easy monetary policy (including unconventional policies).

The problem we have now is that with rates so close to zero (or even negative in some countries), central banks are powerless to tame the turmoil by conventionally cutting interest rates.

Read more: Below zero is ‘reverse’. How the Reserve Bank would make quantitative easing work

It is making investors worried about governments’ abilities to respond in time to contain or reduce the severity of human and economic devastation.

We are dealing with a global health crisis the likes of which has not been seen for 100 years. It will keep investor sentiment fragile and prone to sudden shifts.

If the last two weeks is anything to go by, the resulting volatility will test the normal functioning of markets.

Faster and more jumpy

There is no formal definition of a market crash, but what we see here has all the hallmarks:

• a 20% decline in equity markets, which defines a bear market, has been achieved in two weeks.

• rates of transacting (velocity) across global markets has been high and a good deal higher than in previous crises. Electronic systems provide a catalyst to embed the panic (uncertainly) into the pricing. We’ve seen huge swings in prices, at increased transaction rates.

In the US, market circuit breakers have been triggered in both falling and rising markets. Black Thursday saw a 15-minute trading hold at the opening to prevent a free fall of stock prices. A day later the New York Stock Exchange’s “limit-up” brake was triggered.

Read more: How will coronavirus affect property prices?

Transaction costs have been inflated with the “spread” between buying and selling prices widening significantly compared with pre-crisis levels, and almost twice what it was during the GFC.

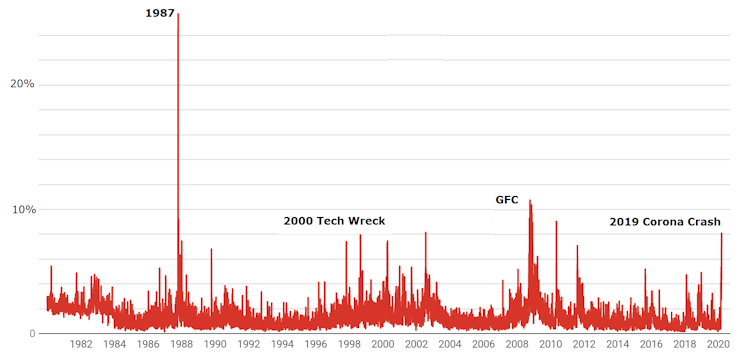

Intraday volatility (the swing from high to low within one day) is approaching what was observed during the global financial crisis.

US S&P500 Index intraday change from high to low

This is not limited to prices; there is also significant intraday volatility in trading volumes, creating uncertainty in the ability to transact effectively, if at all, in the less traded stocks.

The panic response has been quickly entrenched in the price of stocks, distorting effective resource allocation and the management of risk in markets.

That is another way of saying markets are not working well at the moment.

The panic sell-off has seen markets become highly correlated, with “crisis contagion” spreading to all markets and countries. This can be thought of in much the same vein as the COVID-19 pandemic – contagion results from a shock in one or a group of countries or markets, and spreads to others.

It’s shutting down markets

This has real repercussions. New debt issuance has ground to halt around the world.

Even the highest quality government borrowers are finding it hard to sell new securities in this market. Corporations have no chance. This increases the re-financing risk for large corporations, and even banks.

For wage earners, the market crash should be of little consequence. What matters to workers is employment and the number of hours worked.

Read more:

We're staring down the barrel of a technical recession as the coronavirus enters a new and dangerous phase

The fate of workers, particularly those employed in heavily-exposed industries, will be determined by whether the economy can navigate the crisis without a surge in unemployment and business failures.

Superannuants, on the other hand, will be directly and immediately affected.

Superannuants at risk and noticing

Large super funds (super funds with more than four members) held A$912 billion of Australian and international listed shares at the end of 2019, according to Australian Prudential Regulation Authority data. That’s 47% of their total assets of $1.928 billion.

With digital technology, superannuants can get almost real time portfolio valuations.

For those who are invested in the standard growth fund and care to look up the latest numbers, they are down at least 10% in two weeks.

Retirees might spread contagion

For self-funded retirees, Australian bank stocks are very popular. An investment of $100,000 of Australian banks stocks at the start of February is now worth about $75,000. And that is after the spectacular rally on Friday.

This greater access to information and the baby boomer retirement bulge means the wealth effects from large falls in share prices will probably be felt more than in the past.

If the crash turns into a sustained bear market, the risk is that this will become one of the key mechanisms by which the economy is driven down.

This is not limited to prices; there is also significant intraday volatility in trading volumes, creating uncertainty in the ability to transact effectively, if at all, in the less traded stocks.

The panic response has been quickly entrenched in the price of stocks, distorting effective resource allocation and the management of risk in markets.

That is another way of saying markets are not working well at the moment.

The panic sell-off has seen markets become highly correlated, with “crisis contagion” spreading to all markets and countries. This can be thought of in much the same vein as the COVID-19 pandemic – contagion results from a shock in one or a group of countries or markets, and spreads to others.

It’s shutting down markets

This has real repercussions. New debt issuance has ground to halt around the world.

Even the highest quality government borrowers are finding it hard to sell new securities in this market. Corporations have no chance. This increases the re-financing risk for large corporations, and even banks.

For wage earners, the market crash should be of little consequence. What matters to workers is employment and the number of hours worked.

Read more:

We're staring down the barrel of a technical recession as the coronavirus enters a new and dangerous phase

The fate of workers, particularly those employed in heavily-exposed industries, will be determined by whether the economy can navigate the crisis without a surge in unemployment and business failures.

Superannuants, on the other hand, will be directly and immediately affected.

Superannuants at risk and noticing

Large super funds (super funds with more than four members) held A$912 billion of Australian and international listed shares at the end of 2019, according to Australian Prudential Regulation Authority data. That’s 47% of their total assets of $1.928 billion.

With digital technology, superannuants can get almost real time portfolio valuations.

For those who are invested in the standard growth fund and care to look up the latest numbers, they are down at least 10% in two weeks.

Retirees might spread contagion

For self-funded retirees, Australian bank stocks are very popular. An investment of $100,000 of Australian banks stocks at the start of February is now worth about $75,000. And that is after the spectacular rally on Friday.

This greater access to information and the baby boomer retirement bulge means the wealth effects from large falls in share prices will probably be felt more than in the past.

If the crash turns into a sustained bear market, the risk is that this will become one of the key mechanisms by which the economy is driven down.

Authors: Kylie-Anne Richards, Lecturer, Finance Discipline, University of Technology Sydney