Indigenous pain and protest written in the history of signatures

- Written by Trish Luker, Senior lecturer, University of Technology Sydney

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains the names and voices of deceased people.

When was the last time you signed your name? Perhaps you are more familiar with the frustrations of trying to insert a digital image of your cursive signature into an inadequate space in a PDF document? You have probably used a Personal Identification Number, a digital fingerprint, your finger or a stylus on an electronic pad.

In European contexts, the signature is a performative act with a long history. In medieval times, rather than signing a name, people placed hands on a bible, uttered oaths, broke objects, signed the cross or exchanged a lock of hair. From these non-documentary forms, the signature developed as a form of validation to transform a written document into a legal action. It became standard practice in the 17th century – a compulsory addition to legal documents, even if the signatory was illiterate.

Legal history

Despite its significance, there has been little judicial guidance to defining the signature.

In Australia and the United Kingdom, courts have accepted different types of signatures, from seal imprints to rubber stamps, fingerprints, initials, a partial signature, words other than a name, a trade name, printed names as well as the traditional handwritten signature. More recently, signatures appearing on faxes, PDFs and on emails have all been accepted as valid.

Signatures are evidence of the will or intent of the person signing and provide insight into the history of legal documents.

In 2000, the Federal Court of Australia decided a thumbprint was a signature that proved a mother’s consent to the removal of her child. Peter Gunner and Lorna Cubillo, members of the Stolen Generations, sued the federal government seeking compensation for the harm they suffered as a result of being taken away from their families and sent to residential schools.

Taken from Utopia

Peter Gunner was seven years old in 1956 when he was taken from his home at Utopia, in the Northern Territory.

A significant, and notorious, piece of evidence in the case was a document titled Form of Consent by a Parent. This was a proforma document, phrased as a request that Gunner be taken away to St Mary’s Hostel and given a Western education.

On the bottom of the form there is a thumb or fingerprint and the name of Gunner’s mother, Topsy Kundrilba. On the basis of this evidence, the court concluded Gunner had been removed at his mother’s request.

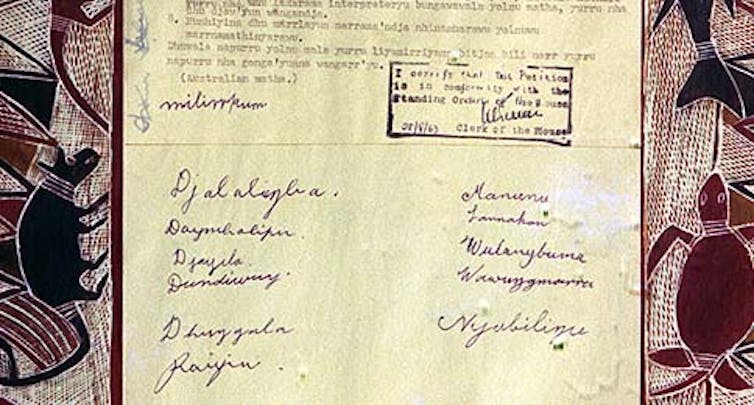

Yirrkala Bark Petition, 1963.

Yirrkala Bark Petition, 1963.

Signatures appear on other legal documents involving Indigenous people in Australia, such as petitions where they are signs of political action.

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions were sent in August 1963 to both houses of federal parliament by the Yolngu people living in the area of Yirrkala, Arnhem Land. The petition followed the granting of mining leases without any consultation with the people of Yirrkala.

These petitions are cross-cultural documents written in both Yolngu Matha and English. They follow the Westminster form and are presented on painted bark boards depicting country. The petitions protested the excision of land from the reserve where the Yolngu people live, hunt and where their sacred sites are located. They are now on display in Parliament House.

Yirrkala Bark Petitions - considered Australia’s Magna Carta. Hear the voice of Dela Yunupiŋu reading the 1963 Yirrkala Bark Petitions in Yolngu. Dela is the daughter of Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu, a senior Gumatj cultural leader who was one of the original signatories of the petition in 1963. You can view the petitions on the AIATSIS website https://aiatsis.gov.au/collections/collections-online/digitised-collections/yirrkala-bark-petitions-1963.More than words

As bark paintings that frame paper with words and signatures, the Yirrkala Petitions demonstrate an innovative cross-cultural legal documentary form: they are symbols of Yolngu title deeds to country.

Because the then Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Paul Hasluck, questioned the validity of the signatures, the Yolngu people followed up with another document, this time on paper, which contains the names and signatory marks of the leaders of every clan group represented.

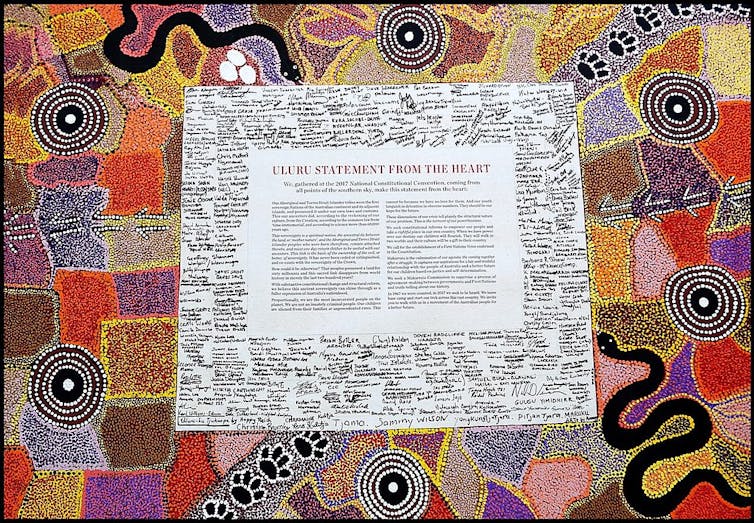

On 26 May 2017, 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people signed the Uluru Statement from the Heart, calling for a First Nations Voice in the Australian Constitution and a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement making and truth telling between government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The statement, written in the centre of a large canvas with paintings that tell the creation stories of the traditional owners of Uluru, the Anangu people, is surrounding by 250 signatures.

The 2017 Uluru Statement From the Heart features artwork and signatures.

Wikimedia, CC BY

The 2017 Uluru Statement From the Heart features artwork and signatures.

Wikimedia, CC BY

The guiding principles for the statement draw on a lengthy history of political campaigns represented in petitions, including the Yirrkala Bark Petitions and the Barunga Statement, presented by the Jawoyn community in Northern Territory to the then Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, in 1988. It is a unique legal document that makes a formal claim on the Australian people and our governing institutions. The statement affirms the sovereignty of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and that sovereignty has never been ceded or extinguished, but it co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

Such Indigenous declarations of sovereignty demonstrate the way signatures can be mobilised as a sign to transform written documents into legal actions. In this way, they seek to inaugurate a new form of legality.

Reading the signs was made by Impact Studios at the University of Technology, Sydney - a new audio production house combining academic research and audio storytelling. This podcast is available for download through the award winning History Lab podcast. It is the third episode in the four-part series, The Law’s Way of Knowing.

Authors: Trish Luker, Senior lecturer, University of Technology Sydney

Read more https://theconversation.com/indigenous-pain-and-protest-written-in-the-history-of-signatures-130458