when the world catches on fire, how do predators respond?

- Written by Euan Ritchie, Associate Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

2019 might well be remembered as the year the world caught fire. Some 2.9 million hectares of eastern Australia have been incinerated in the past few months, an area roughly the same size as Belgium. Fires in the Amazon, the Arctic, and California captured global attention.

As climate change continues, large, intense, and severe fires will become more common. But what does this mean for the animals living in fire-prone environments?

Read more: Drought and climate change were the kindling, and now the east coast is ablaze

Our new research, published recently in the Journal of Animal Ecology, looked at studies from around the world to identify how predators respond to fire.

We found some species seem to benefit from fires, others appear to be vulnerable, and some seem indifferent. In a changing climate, it’s urgent we understand how fires affect predators – and hence potentially their prey –in order to keep ecosystems healthy.

Predators: the good and the bad

Large predators, like wolves and lions, often play important roles in ecosystems, regulating food webs by reducing the numbers or changing the behaviour of herbivores and smaller predators. Many large predators are in dire straits within their native range, while introduced predators, such as feral cats and red foxes, have spread to new regions, where they have devastated native wildlife .

Fires can offer new opportunities as well as problems to predators. Some predators take advantage of charred, more open landscapes to hunt vulnerable prey; others rely on thick vegetation to launch an ambush.

But until now, we have not known which predators are drawn to fire, which are repelled by it, and which don’t care either way. Synthesising information on how different kinds of predators (for example, large or small, pursuit or ambush) respond to fire is vital for both the conservation of top predators and to help protect native prey from introduced predators.

Predators are reacting differently to fire.

Adam Stevenson/Reuters

Predators are reacting differently to fire.

Adam Stevenson/Reuters

Some like it hot

Our research reviewed studies from around the world to identify how different vertebrate predators (birds, mammals and reptiles) respond to fire in different ecosystems.

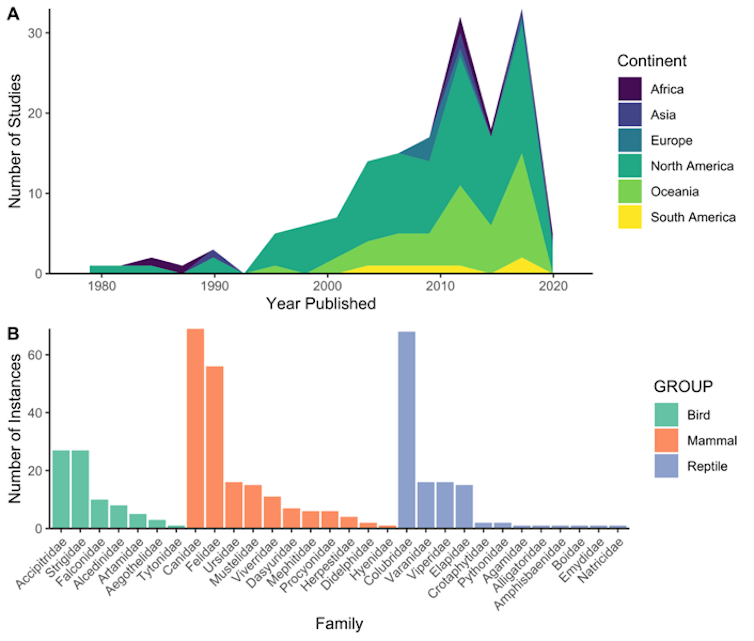

We found 160 studies on the response of 188 predator species to fire, including wolves, coyotes, foxes, cats, hawks, owls, goannas and snakes, amongst others. The studies came from 20 different countries, although most were from North America or Australia, and focused on canine and feline species.

Some predators seem to like fire: they are more abundant, or spend more time in, recently burnt areas than areas that escape fire. Our review found red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) mostly responded positively to fire and become more active in burned areas.

Raptors have even been observed in Northern Australia carrying burning sticks, helping to spread fire and targeting prey as they flee the fire.

For other predators, fire is bad news. Following Californian wildfires, numbers of eastern racer snakes fell in burnt areas. Likewise, lions avoid recently burned areas, because they rely on dense vegetation from which to ambush prey.

A global summary of studies examining predators and fire.

A global summary of studies examining predators and fire.

The authors of the papers we reviewed thought food availability, vegetation cover, and competition with other predators were the most important things affecting species’ responses to fire.

But perhaps more surprising was that most species, including bobcats and the striped skunk, appeared largely unaffected by fire. Of the affected species, some (such as spotted owls) responded differently to fire in different places.

Overall, we found it is difficult to predict how a predator species will respond to fire.

We still have a lot to learn

Our results show while many predators appear to adapt to the changes that fires bring about, some species are impacted by fire, both negatively and positively. The problem is that, with a few exceptions, we will struggle to know how a given fire will affect a predator species without local knowledge. This means environmental managers need to monitor the local outcomes of fire management, such as fuel reduction burns.

There may be situations in which predator management needs to be coupled with fire management to help prevent native wildlife becoming fox food after fire. There has even been trials to see if artificial shelters can help protect native wildlife from introduced predators after fire.

Getting our knowledge base right

One thing that has hampered our research is the lack of contextual information in many studies. No two fires are the same – they differ in size, intensity, severity, and season – but these details are often absent. The literature is also biased towards dog-like and cat species, and there are few studies on the response of predators to fire in Africa, Asia, and South America.

It is important to note that some predator responses to fire may be overlooked due to the way experiments were carried out, or because monitoring happened too long after the fire.

Unifying how fire, predator numbers and environmental features are recorded would help future studies predict how predators might react to different types of fires in various situations.

Read more: Bushfires are pushing species towards extinction

As wildfires become more frequent and severe under climate change, understanding how fire intensity and frequency shapes predator populations and their prey will be critical for effective and informed ecosystem management and conservation.

Authors: Euan Ritchie, Associate Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University