Clive James spent his salad days in good company

- Written by Laura Ginters, Senior Lecturer, Department of Theatre and Performance Studies, University of Sydney

Many remember Clive James as the wry television presenter, but long before his small screen success, he honed his performing and writing skills at the University of Sydney.

Arriving as a 16-year-old fresher in 1957, James found himself surrounded by an exceptionally talented group of young people including, among others, Bruce Beresford, John Bell, John Gaden, Leo Schofield, Madeline St John, Richard Wherrett, Ken Horler, Robert Hughes and, soon after, Germaine Greer.

As James himself recognised, they were the lucky beneficiaries of a generous Commonwealth Scholarship Scheme:

Menzies educated the whole generation that would later on vilify his memory. That made all the difference as we were all at university.

It was right time, right place, and these students revitalised drama on campus, drawing the attention of mainstream critics with their stylish productions of the classics, and some of the most innovative contemporary drama from England and Europe, in addition to the irreverent, political and satirical annual university revues they themselves wrote and staged.

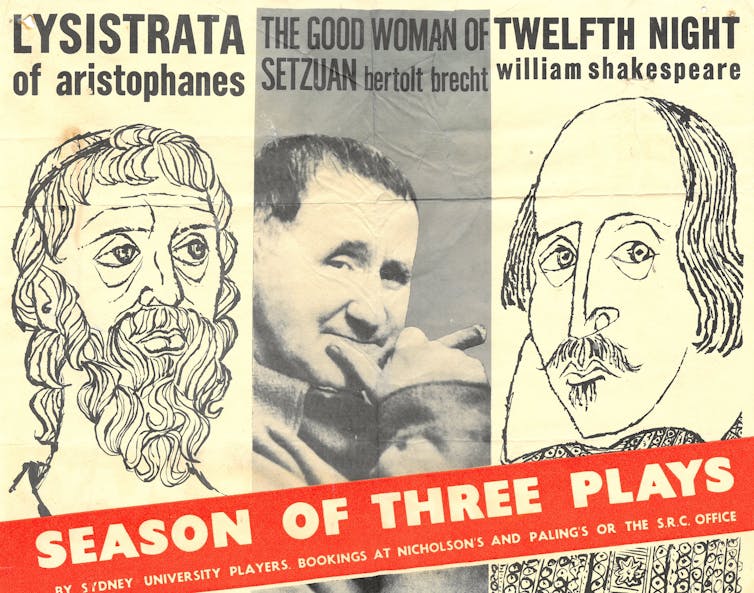

Sydney University’s season of three plays.

Author provided (No reuse)

Sydney University’s season of three plays.

Author provided (No reuse)

In revues

James was a prolific writer, contributing a steady stream of articles, poems and reviews to the student newspaper, Honi Soit. He documented the torrent of productions, including the world stage premiere of Beckett’s radio play All That Fall, Leo Schofield’s somewhat subversive production of HMS Pinafore, and he especially loved Ken Horler’s direction of Capek’s satirical Insect World, singling out Rosaleen Smyth as “a star” in the making.

“I can think of no other thing to say about her that could convey the way I see this actress,” wrote James, although as he was well known to be smitten with Smyth, his journalistic objectivity was shaky at best.

By 1958 he had launched himself into writing for the university revues: his skits were so good that they were recycled in revues for years to come.

His funny take on the Helen of Troy myth featured in the 1960 revue. In it actor Jenny Towndrow burst onto the stage (“like a nuclear explosion” according to Honi Soit), as Cassandra, singing:

Zippy de do dah

Zippy de eh

I’ve had a hint of a horrible day

Hordes of destruction heading our way

Zippy de do dah

Zippy de eh…

Having completed her calamitous prophesy she skipped off again, and Priam and Hecuba deadpanned:

Priam: She’s a gloomy girl.

Hecuba: Never liked to play with the other children.

Inherent vice

In 1961, James not only directed the revue, Wet Blankets, but also wrote eight of its 14 skits. He had, according to his contemporaries, very clear ideas on how his work should be performed – indeed, some believed he wanted to perform all his own work himself.

Clive James and Brian Sommers co-directed Wet Blankets.

Author provided (No reuse)

Clive James and Brian Sommers co-directed Wet Blankets.

Author provided (No reuse)

James was keenly aware of the powerful lure of the stage. The previous year the Sydney University Players staged an ambitious season of plays, with profits being donated to the Sydney Opera House Building Fund.

Schofield directed the Australian premiere of Brecht’s Good Woman of Setzuan, and Horler (later one of the founders, along with Bell, of the Nimrod Theatre) created a highly acclaimed production of Twelfth Night, starring Bell as Malvolio and Gaden as Sir Toby Belch. But the season kicked off in a city theatre, with Lysistrata.

In this classic Greek comedy, set in the Trojan Wars, the womenfolk deny their fighting men sex as a strategy to end the wars. This “sex theme” attracted the attention of the state censor, who two years later would ban one of Bruce Beresford’s early student films, It Droppeth As the Gentle Rain, for obscenity.

Two policemen dutifully attended the first performance of Lysistrata but no further action was taken. On the second night of the season, with the vice squad safely out of the way, James bounced on stage as a Spartan herald – with a large, rolled scroll strategically angled under his very short Grecian tunic. James revelled in the audience’s delighted reaction.

One-time girlfriend Jill Kitson (who became an ABC broadcaster), was also in the cast, and vows this was the moment from which James set out to publicly perform as part of his brilliant career. Writing decades later, Schofield reflected that those who had seen the production “recognised early two … of Clive’s ruling passions, sex and showbiz”.

James was among the Brilliant Creatures who led the cultural revolution of the 1960s.Lasting legacy

The friendships and collaborations formed while television was in its infancy have flourished for over six decades and enriched cultural life in Australia and beyond.

In an interview for our book The Ripples Before the New Wave: Drama at the University of Sydney 1957-63, James modestly told Robyn Dalton and myself he was convinced:

One day we’ll all be remembered, if we are, because we once knew Madeleine St John. She was the genius; we didn’t know it at the time.

St John, the first Australian nominated for the Booker Prize, wrote a series of sparkling novels James loved. Her book Women in Black follows the lives of a group of department store employees in 1959 Sydney and includes a main character based on another of James’ university friends. James recommended it to Beresford who optioned the film rights.

The character of Lisa (Angourie Rice) in Ladies in Black was based on Colleen Olliffe (Chesternan) – a university friend of James, Beresford and St John.

IMDB

The character of Lisa (Angourie Rice) in Ladies in Black was based on Colleen Olliffe (Chesternan) – a university friend of James, Beresford and St John.

IMDB

Beresford’s acclaimed 2018 film, Ladies in Black, is a loving tribute to the era when this group of young people were taking their first steps in their adult lives.

James’ contributions then, and since, will ensure that he too, will be long and fondly remembered.

Authors: Laura Ginters, Senior Lecturer, Department of Theatre and Performance Studies, University of Sydney