what studying Macbeth in Queensland could teach us about place and shipwrecks

- Written by Claire Hansen, Lecture in English/Writing, James Cook University

When you imagine the setting for Macbeth, misty heaths, battlefields, and the brooding highlands spring to mind. Teaching the play in the midst of a tropical summer in Townsville, far north Queensland, highlights disjunctions and surprising correlations between play and place.

In their 2011 book Ecocritical Shakespeare, Lynne Bruckner and Dan Brayton consider this relationship between our environment and our practices of reading, writing about, and teaching Shakespeare:

What does the study of literature have to do with the environment? … What is the connection between the literary and the real when it comes to ecological conduct, both in Shakespeare’s era and now?

One way of answering these questions is through the use of place-based education. Educational theorists Amanda Hagood and Carmel E. Price reason that “student learning is enhanced when course content is grounded in a particular place of meaning”.

This approach is neither new nor (on the surface) complex. Educational philosopher John Dewey prioritised experiential learning such as nature studies. More recently, Swansea University educators have published research on the benefits of curriculum-based outdoor learning for primary school students.

But preliminary research on outdoor Shakespeare education conducted with Townsville secondary school students shows contradictory responses: some students found the location “calming” and “less stressful” than classrooms. Others believed that learning did not “rely on location”.

Christopher Gaze founded Vancouver’s Bard on the Beach Shakespeare Festivalin 1990. Attendance at the beachside performances has since topped 91,000.Students’ sense of place

In 2019, 60 first-year English students at James Cook University were asked to rate the importance of setting in Shakespeare plays, and the importance of their own place to the study of Shakespeare.

Of those surveyed, 85% felt that the setting was important to the play, while 96% believed that Shakespeare had little or no relevance to their local area. Few felt that their real life location was important in their study of the playwright’s work.

These results show a contrast between the perceived value of literary and of lived place. This is problematic: how do students engage with fictional, imagined literary places if their own lived experience of place is devalued?

When asked to explain their ratings, students said:

I believe the setting plays a big part in the play as it allows the audience to understand why the characters are doing what they are doing. Shakespeare isn’t important in Townsville.

I live in a rural area. There is not a lot of room for Shakespeare - though given small town conflicts you would see his plots acted out in real life.

There is slippage here between the student’s reference to physical place and their conceptual space, which does not have a lot of cultural room for Shakespeare.

A third student wrote:

My family doesn’t really care about Shakespeare, but I do enjoy some of his works personally.

Here, place was understood to refer to relationships, not environment - an understanding backed by British social scientist and geographer Doreen Massey’s theories.

The disparity between students’ conceptualisations of place and their devaluation of their own location as relevant to their studies may be symptomatic of what Alice Ball and Eric Lai identify as “an ethos of placelessness in education”. In Canada, David Gruenewald has argued that the curriculum is largely “placeless”, with educational reforms and high stakes testing increasingly disconnected from our places.

Shakespeare’s shipwrecks

One approach to teaching Shakespeare through place-based education could centre on shared spaces in lived place and text. As a Shakespeare scholar living near the Great Barrier Reef, I’m interested in what Steve Mentz identifies as the “blue ecology” of Macbeth; the play’s many references to the ocean, liquids, and bodily fluids.

One blue image common to both Shakespeare and Townsville is that of the shipwreck – a favourite trope of Shakespeare’s, essential to plays including The Comedy of Errors, Twelfth Night, The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and Pericles.

Macbeth invokes shipwreck imagery with a tale of changed fortune after Macbeth’s victory over the traitor Macdonald:

As whence the sun ‘gins his reflection,

Shipwrecking storms and direful thunders break,

So from that spring, whence comfort seemed to come,

Discomfort swells.

The Witches offer a literal description of a ship or “bark”:

1 WITCH

Though his bark cannot be lost,

Yet it shall be tempest-tossed.

2 WITCH

Show me, show me.

1 WITCH

Here I have a pilot’s thumb,

Wrecked as homeward he did come.

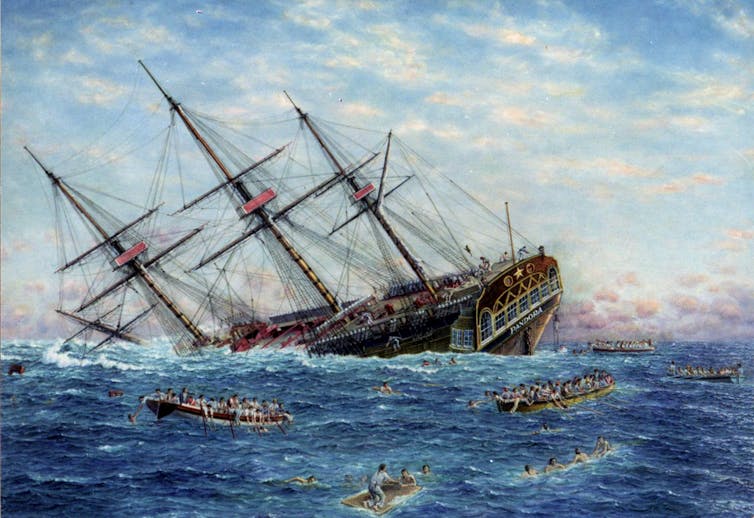

Shipwreck is something that Shakespeare and Townsville have in common. Two of the most famous shipwrecks off Townsville’s coast are the SS Yongala (which sank in 1911 and is now a popular diving site) and the HMS Pandora (hulled on the Great Barrier Reef in 1791 after capturing some of the Bounty mutineers; remnants of the wreckage are on display at the Museum of Tropical Queensland in Townsville).

HMS Pandora was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef off north Queensland in 1791, while shipwrecks are a common Shakespearean trope.

Museum of Tropical Queensland/AAP

HMS Pandora was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef off north Queensland in 1791, while shipwrecks are a common Shakespearean trope.

Museum of Tropical Queensland/AAP

Our students could both explore Shakespeare through the shipwreck and engage more with the history and culture of their own local places. This approach requires us to think about place as real and imagined; fitting for Macbeth, a play defined as a “tragedy of imagination”.

Authors: Claire Hansen, Lecture in English/Writing, James Cook University