Cosmic theorist and planet-hunters share physics prize as Nobels reward otherworldly discoveries

- Written by Michael Cowley, Astrophysics Research and Teaching Associate, Queensland University of Technology

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to three researchers for their contributions to two unique fields.

Half of the 9 million Swedish krona (A$1.34 million) award goes to James Peebles, a Canadian cosmologist at Princeton University, “for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology”.

Read more: Nobel Prize in Physics: James Peebles, master of the universe, shares award

The other half is split between two Swiss astronomers, Michel Mayor of the University of Geneva, and Didier Queloz from the University of Geneva and University of Cambridge, “for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star”.

Göran Hansson, Secretary General of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, said that together, these contributions provide us with an “understanding of the evolution of the Universe and Earth’s place in the cosmos”.

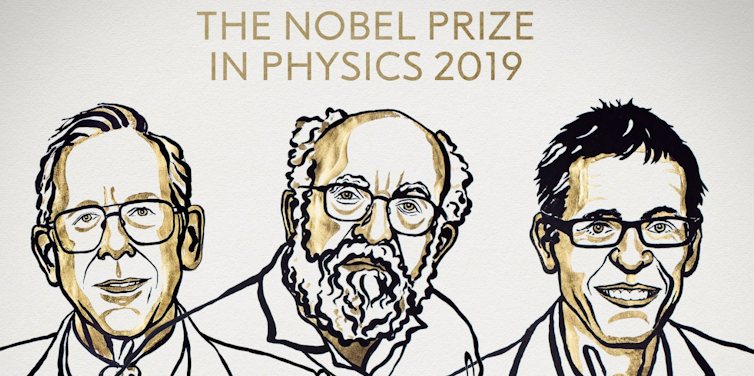

L-R: James Peebles, Michel Mayor, Didier Queloz.

Niklas Elmedhed/Nobel Media.

L-R: James Peebles, Michel Mayor, Didier Queloz.

Niklas Elmedhed/Nobel Media.

Cosmology

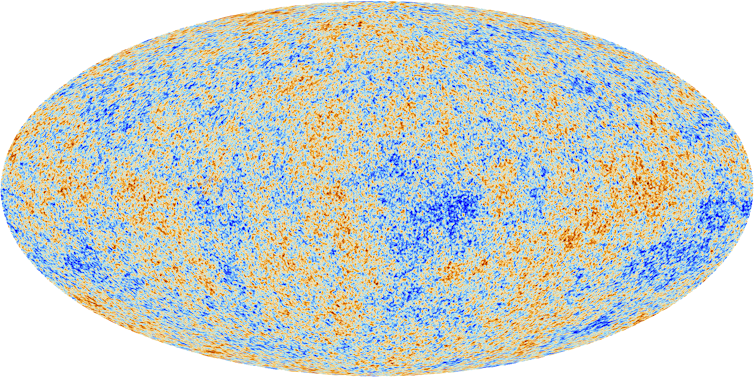

Peebles’ theoretical calculations have allowed cosmologists to interpret the cosmic microwave background (CMB), leftover radiation from the aftermath of the Universe’s birth 13.8 billion years ago. Discovered by accident more than 50 years ago, the CMB represents a goldmine for cosmologists, containing secrets to the Universe’s origins, age, and composition.

The cosmic microwave background, based on Planck data.

ESA and the Planck Collaboration

The cosmic microwave background, based on Planck data.

ESA and the Planck Collaboration

While Peebles’ theoretical framework has provided the key to unlocking the secrets of the CMB, it has also left cosmologists with an even bigger question – one that revolves around the composition of the Universe.

Currently, regular matter – the stuff that makes up the stars, the planets, and everything on Earth – is believed to comprise only 5% of the total mass and energy in the Universe. The remainder includes a mixture of dark matter (25%), a mysterious form of matter that is invisible to traditional observational techniques, and dark energy (70%), which is thought to be the reason for the Universe’s expansion.

Read more: From dark gravity to phantom energy: what's driving the expansion of the universe?

While these “dark” components remain mostly elusive, the pioneering work of US astronomer Vera Rubin proved almost beyond doubt that dark matter exists. Rubin’s ideas revolutionised cosmology, but sadly she never won a Nobel Prize and passed away in 2016.

Exoplanets

Mayor and Queloz were honoured for their 1995 discovery of an exoplanet – a planet outside our Solar system – orbiting a Sun-like star.

Using custom-made instruments on the Observatoire de Haute-Provence telescope in France, Mayor and Queloz observed a distant star in the constellation Pegasus, called 51 Pegasi, and found it to be wobbling.

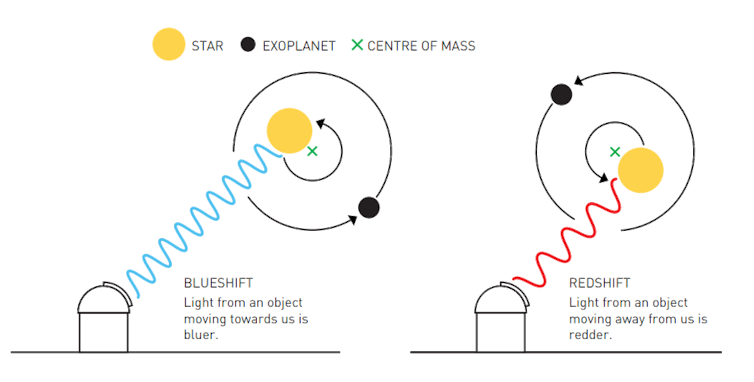

This wobble is caused by the gravitational effects of a planet tugging on its host star and is observable via the changing nature of the star’s light. When viewed by a distant observer, the wobble affects the star’s light spectrum. If the star is moving towards an observer, its spectrum appears slightly shifted towards the blue end, but if it is moving away, it is shifted towards the red end.

By looking at these “Doppler shifts” using an observational method known as radial velocity, astronomers can not only detect the presence of a planet, but also estimate its mass and orbital period (the length of the planet’s “year”).

Radial velocity method of detection.

Johan Jarnestad/Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Radial velocity method of detection.

Johan Jarnestad/Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Mayor and Queloz discovered a Jupiter-mass planet, dubbed 51 Pegasi b. Its orbital period was just 4.2 days, compared with Earth’s 365-day journey around the Sun. This itself was a surprise, as astronomers didn’t expect such a massive planet to orbit so quickly and closely around its host star. The discovery gave rise to the nickname “hot Jupiter” for these types of planets, and heralded a new era of exoplanet research.

Read more: Nobel Prize in Physics for two breakthroughs: Evidence for the Big Bang and a way to find exoplanets

Today, more than 4,000 exoplanets have been discovered in the Milky Way galaxy, with many more expected in the years to come. Besides giving astronomers new insights into how our Solar system and its planets formed and evolved, exoplanet research may also answer the ultimate question of whether we are alone in the Universe.

Authors: Michael Cowley, Astrophysics Research and Teaching Associate, Queensland University of Technology