Disability and single parenthood still loom large in inherited poverty

- Written by Deborah Ann Cobb-Clark, Professor of Economics, University of Sydney

Australians like to think we live in a country of the fair go, where anyone with the talent and willingness to work hard can succeed.

But the evidence show success is still partly inherited. Children with poor parents are more likely to grow up and be poor as adults.

Read more: Here's why it's so hard to say whether inequality is going up or down

The latest biennial report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare highlights the ways in which social and economic position is transmitted between generations.

Research points to several key factors in inherited disadvantage — notably parental disability, family structure and unemployment.

Gender patterns

Understanding the nature and extent of inherited disadvantaged in Australia has been aided by five significant research studies in the past five years. Four of them use data from the comprehensive Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The fifth used tax records to estimate the intergenerational mobility of people born between 1978 and 1982.

Among the results to come from these studies are estimates of the degree to which a 10% increase in fathers’ earnings affect their sons’ earnings. The studies offer a range of 1% to 3.5% – with a higher percentage meaning less social mobility.

One study highlights some interesting gender variations. It found a 10% increase in a father’s earnings associated with a 2% increase in sons’ earnings, but only a 0.8% increase in daughters’ earnings. A 10% increase in mothers’ earnings was linked to a 1.6% increase in sons’ earnings and a 1.5% increase in daughters’ earnings. This suggests girls’ earning trajectories are slightly less determined by their parents’ experience.

Other findings, however, point to certain types of disadvantage being most inherited by women. For example, those raised by a single parent receiving parenting payments are 2.2 times more likely to become a single-parent payment recipient themselves – and women make up more than 80% of single-parent payment recipients.

Patterns of transmission

The single-parenthood pattern was among those identified in research published in 2017 by myself, Sarah Dahmann, Nicolas Salamanc and Anna Zhu. The importance of family structure is underlined by the fact young adults are more likely to receive a range of welfare payments if they grow up in single-parent families.

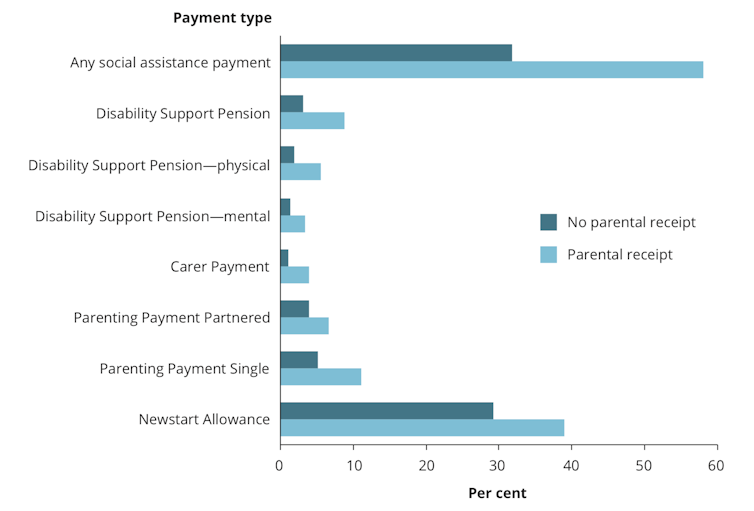

The following graph shows the results of our research.

A larger disparity in the relative chance of receiving welfare given parental welfare receipt indicates a greater degree of intergenerational transmission of disadvantage.

AIHW, Australia’s welfare 2019 data insights, Author provided (No reuse)

A larger disparity in the relative chance of receiving welfare given parental welfare receipt indicates a greater degree of intergenerational transmission of disadvantage.

AIHW, Australia’s welfare 2019 data insights, Author provided (No reuse)

Overall, we found young Australians aged 18-26 were 1.8 times more likely to receive welfare if their parents ever received welfare. That is, 58% of young people whose parents ever received welfare were also on welfare, compared with 31.8% of those whose parent were not.

Young people whose parents received unemployment payments while they were growing up were 1.6 times more likely to receive unemployment payments before age 22, and 1.3 times after age 22.

Intergenerational disability

But the strongest relationship in intergenerational disadvantage involves parental disability.

Our results showed young people whose parents received disability support payments were 2.8 times more likely to receive disability support payments.

Young people whose parents received the Disability Support Pension for mental health reasons were almost three times as likely to be receiving the mental health-related disability benefits as other young people. They were also more likely to need other social assistance payments

The intergenerational relationship between youth unemployment and parental disability, for example, and was just as strong as that with parental unemployment.

These findings do not imply that poor children would have been better off had their parents not received social assistance — only that poor children are more likely to need assistance than non-poor children.

Stretching the rungs

Social mobility is higher in Australia than many other developed countries (most notably the United States). But it remains lower than the Scandinavian countries, and is threatened by any increase in inequality.

Read more: What the Bureau of Statistics didn't highlight: our continuing upward redistribution of wealth

A growing gap between richest and poorest grows pulls the the rungs of the socioeconomic ladder further apart, making it harder for disadvantaged Australian children to avoid becoming disadvantaged adults.

Authors: Deborah Ann Cobb-Clark, Professor of Economics, University of Sydney