Glamorising violent offenders with 'true crime' shows and podcasts needs to stop

- Written by Xanthe Mallett, Forensic Criminologist, University of Newcastle

Even in death, the voice of Carl Williams is louder than that of his victims. Intimate prison letters written by the convicted murderer and drug trafficker to his ex-wife, Roberta – herself arrested this month on kidnap and threats to kill charges, allegedly made against a documentary producer – were published this month.

The explosion of true crime in podcasts, streaming series, and books has fuelled our interest in violent and dangerous perpetrators, and has increasingly meant the victims continue to be overlooked.

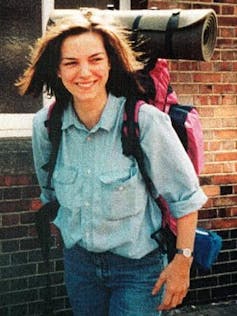

British backpacker Caroline Clarke was one of Ivan Milat’s seven known victims.

AAP

British backpacker Caroline Clarke was one of Ivan Milat’s seven known victims.

AAP

Indeed, Ivan Milat, Ted Bundy, and Jeffrey Dahmer are household names. Yet Deborah Everist, Caryn Campbell, or Tony Hughes – victims of these violent killers, have been largely forgotten.

Deadly charms

My students and I often watch true crime documentaries as stimuli for discussion about criminal causation, or victim selection. Recently, a student in one such tutorial expressed admiration for notorious US serial killer Ted Bundy, even going as far as to say she was attracted to him – or at least Hollywood heartthrob Zac Efron’s portrayal of him.

Bundy killed at least 30 women, assaulted many more, and escaped prison twice. He was perhaps active from the late 1960s until 1978. Bundy was the subject of a recent four-part Netflix series entitled Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, billed as “present-day interviews, archival footage and audio recordings made on death row”.

Zac Efron plays up Ted Bundy’s killer charm in the recent Netflix series.The series premiered in January, to coincide with the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s execution. Netflix followed this factual account of Bundy’s crimes with a film about the case called Extremely Wicked and Shockingly Evil and Vile, starring Efron.

I found my student’s affection for him confronting. She was willing to overlook the appalling violence because Efron – and this was also true of Bundy – was a charismatic and attractive person.

I was left wondering if the glamorisation of offenders through true crime was making people desensitised to the plight of victims. And, if this was the case, the affect this had on surviving victims and their families.

Some victims are speaking out.

A recent article focused on on Bill Thomas, whose sister Cathy’s 1986 murder in Colonial Parkway, Virginia, remains unsolved. Bill is at the first day of CrimCon, an annual true crime festival, to draw attention to his sister’s murder and put pressure on the FBI to investigate it further. To do that, he has to rub shoulders with people wearing clothes emblazoned with serial killers’ faces.

Serial Killers Gallery at the National Museum of Crime & Punishment in Washington, DC.

WikiMedia

Serial Killers Gallery at the National Museum of Crime & Punishment in Washington, DC.

WikiMedia

We are particularly fascinated by cold cases. Even if we don’t know who the offender is, the salacious details of the crimes overshadow the pain and suffering of victims.

I became painfully aware of this recently while writing a book about cold cases, with the goal to maintain a focus on the victims - each case is included with the hopes of learning something new. A new forensic technique that might progress it, another victim that may be part of the sequence and whose case remains unsolved. Victims’ identities are perversely subsumed into that of the person who offended against them, and I wanted to try to undo some of that.

Focus is shifting

Narcissistic killers like Ivan Milat and Daniel Holdom (who violently murdered Karlie Pearce-Stevenson and her 2-year-old daughter Khandalyce Pearce in 2010) maintain their notoriety by writing letters from prison. Milat’s letters to his nephew, Alistair Shipsey, were published in 2016. Holdom’s letters were turned into a podcast by the Daily Telegraph.

But recent events have seen a shift in focus.

Victimology (the study of victims) is growing as a criminological discipline and academics and victims’ advocates have been saying for some time that the centre needs to shift from the offenders to the victims. But we have largely been shouting into a black hole.

The Christchurch mosque shootings on 15 March 2019, gave voice to a redirection in attention when New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern refused to name the perpetrator – a 28-year-old Australian man who had live-streamed the atrocity and released a manifesto outlining white genocide conspiracy theories. Instead, she urged the public to speak the names of the victims. This was a powerful message that the perpetrator would not be given the attention he sought.

New Zealand went further, making it a criminal offence to copy, distribute, or exhibit the video of the live shootings, with potential penalties of up to 14 years in prison for an individual, or up to $100,000 in fines for a corporation. One man was sentenced to nearly two years in prison for sharing the video that he embellished to look like a video game, including cross hairs and a body count.

Tributes flowed for Sydney woman Michaela Dunn.

AAP/NSW Police

Tributes flowed for Sydney woman Michaela Dunn.

AAP/NSW Police

This week, 24-year-old woman Michaela Dunn was identified as the victim of a Sydney knife attack after she was allegedly killed in a CBD apartment by Mert Ney, 20, before he took his knife to the streets and was overpowered by members of the public. Tributes flowed for the victim, described by her mother as a “beautiful, loving woman who had studied at university and travelled widely”.

Fame can breed copycats

Publicising violent crime and its offenders can lead to further harm in the form of copycat attacks.

Nine days after the Christchurch shootings, there was an arson attack against a mosque in California, followed by a shooting. The offender praised the Christchurch shooter.

Still, my hope is that if Ardern’s ethos is applied to future events, our interest in violent offenders will lessen and our sensitivity to the effect of their crimes will be revived.

We can always learn from true crime events, but we must be careful to move away from glamorisation of perpetrators and pay due respect to the victims and their families.

Authors: Xanthe Mallett, Forensic Criminologist, University of Newcastle