How to know if we’re winning the war on Australia’s fire ant invasion, and what to do if we aren't

- Written by Daniel Spring, Research Fellow, School of Biosciences, University of Melbourne

More than A$400 million of government funding is being invested in the latest round of the fire ant program in the hope of eradicating the invasive pests by 2027.

But recent reports on the ABC suggest the invasion is spreading beyond containment lines in south-east Queensland, and there are delays in responding to public reports of new ant infestations.

The claims are denied by Graeme Dudgeon, the new general manager of Queensland Government’s National Red Imported Fire Ant Eradication Program.

Read more: Koala-detecting dogs sniff out flaws in Australia's threatened species protection

Fire ants are native to South America but nests were first discovered in Brisbane in 2001. It’s thought they arrived via shipping at the Port of Brisbane.

They’re regarded as one of the world’s worst invasive species and have a painful bite which is why the Queensland Government has been trying to wipe them out here.

Is eradication possible?

An independent review in 2016 found the fire ants were confined to a region of south east Queensland and said there was an opportunity to eradicate the pests.

But the latest debate raises the question of whether eradication is the best plan, or would further containing the spread of the fire ants be a more practicable solution?

To achieve its aim of eradicating the fire ant problem, the program needs to progressively shrink the invasion.

If the invasion is shrinking too slowly (or is expanding), eradication won’t be achieved by 2027. Without ongoing monitoring of the invasion’s size, the program might be failing without the general public knowing.

But knowing the fire ant invasion’s size isn’t easy because there isn’t enough funding to survey all locations that might have them.

Estimates of the invasion

Using records of past fire ant detections, we have demonstrated how to estimate the invasion’s size when only part of the managed area is surveyed.

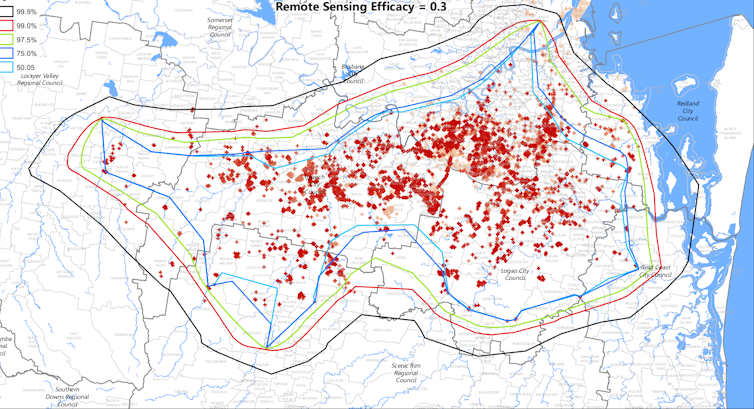

Our inference of the boundary of the fire ant invasion in April 2015. The different coloured polygons correspond to different levels of credibility that the boundary contains the invasion, with the outermost boundary corresponding to the highest credibility. Small crosses represent sites where nests have been detected, with the most recent detections in red and the oldest in brown.

Nature/Authors provided, CC BY

Our inference of the boundary of the fire ant invasion in April 2015. The different coloured polygons correspond to different levels of credibility that the boundary contains the invasion, with the outermost boundary corresponding to the highest credibility. Small crosses represent sites where nests have been detected, with the most recent detections in red and the oldest in brown.

Nature/Authors provided, CC BY

If this approach to estimating the invasion boundary is applied each year during the current program, we could estimate whether the invasion is shrinking fast enough to be gone by 2027.

The importance of this issue demands a rigorous scientific analysis using transparent data and methods. Without this, anecdotal evidence that the current invasion is spreading is all we have to indicate whether eradication efforts are failing.

The size of the fire ant invasion should not only be measured in terms of the total area within its estimated boundary but also the density of nests within this area.

Eradication won’t be achieved if both the invasion boundary and the density within it are increasing. This straightforward test to determine whether the program is failing has not yet been applied.

But such a test could be done if updated records of the fire ant invasion are regularly made available to allow for periodic estimation of updated maps of the invasion.

Never give up

Even if eradication by 2027 is unlikely, this does not mean we should give up, provided future control efforts can contain the invasion at an affordable cost.

If the current program fails to eradicate the fire ants, it may still set the stage for effective long-term containment of the invasion.

A poor outcome will result if current management efforts are spread thinly over the infested area, reducing the density of nests but not eradicating them from any suburbs.

A better outcome would involve shrinking the infested area, that is, eradicating the ants from many or most suburbs, so that subsequent containment efforts can focus resources on a smaller area.

Is it still early enough in Australia to shrink the fire ant invasion to a manageably small area and thereby protect most homes and most of the environment for a long time? The required information to answer this question is not yet available.

Read more: Want to beat climate change? Protect our natural forests

But if Queensland’s eradication program has substantially slowed the spread so far, this provides confidence that continuing the program could effectively suppress the invasion. If so, we need to estimate what it will cost to keep out fire ants from most homes and most of the environment for a long time.

It’s often claimed that removing the last 1% of invaders costs as much as removing the previous 99%. If the current program removes all ants from most areas by 2027, this may provide large benefits without the extra cost of finding the last few ants in all infested areas.

Even if we do eradicate fire ants this time, it’s almost certain they will be back because they can readily hitchhike rides on ships.

So if governments can keep fire ant numbers down through ongoing containment, a lot of people and a lot of native species will benefit.

Authors: Daniel Spring, Research Fellow, School of Biosciences, University of Melbourne