The new Mabo? $190 million stolen wages settlement is unprecedented, but still limited

- Written by Thalia Anthony, Associate Professor in Law, University of Technology Sydney

The Queensland government’s in-principle agreement to pay A$190 million in compensation for the wages withheld from more than 10,000 Indigenous workers is a watershed moment for the stolen wages movement.

Indigenous people across Australia have been fighting for their denied and withheld wages for decades, both on the streets and in the courts. There have been some victories along the way and many setbacks.

The significance of the Queensland settlement (to settle a class action) is that it marks the first recognition these claims have legal as well as moral and political merit. Its ramifications are potentially limited, however, given the full injustice of how Indigenous wages were stolen.

A significant contribution

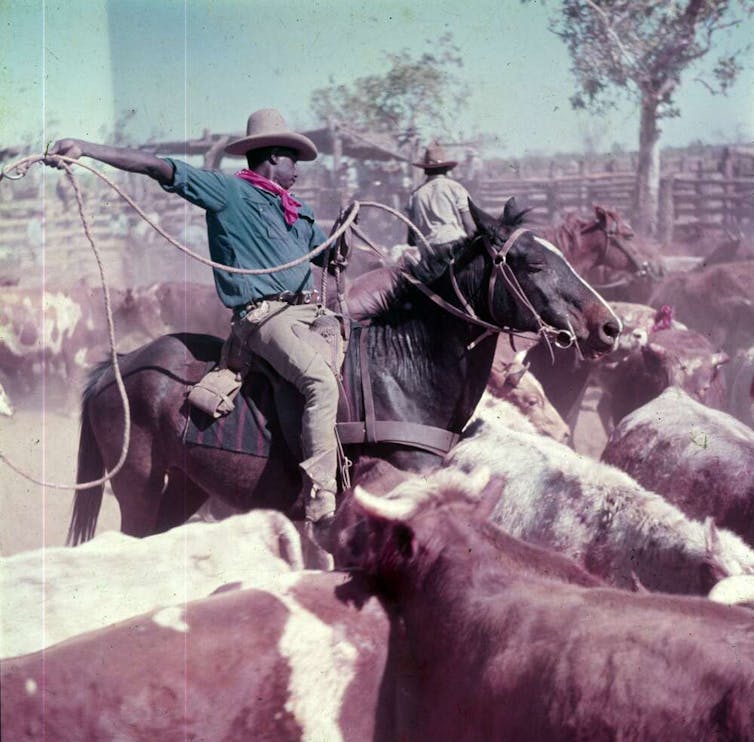

Historically Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women found work in farming, mining, roadbuilding, irrigation, fencing, gardening, pearling, sealing, fishing and domestic duties. But they were most concentrated in the cattle industry of northern Australia, from Western Australia to Queensland.

Tens of thousands worked on cattle stations from the 1880s to 1970s. The beef industry could not have survived without them. In 1913, the federal government’s Chief Protector of Aborigines, Baldwin Spencer, noted that “under present conditions, the majority of cattle stations are largely dependent on the work done by black "boys”. In the 1930s, when the rest of the economy floundered in the Great Depression, Indigenous labour helped keep the industry profitable.

Cattlemen at Victoria River Downs Station, Northern Territory, in 1953.

Frank H. Johnston/National Library of Australia

Cattlemen at Victoria River Downs Station, Northern Territory, in 1953.

Frank H. Johnston/National Library of Australia

Systemic stealing

Indigenous workers were entitled to be paid two-thirds of other workers, but even then employers often paid them less. Sometimes the low value of their wages was disguised by being paid in food and clothing rations. Sometimes workers were provided “store credit”, which could only be used to buy exorbitantly priced items.

Read more: Friday essay: the untold story behind the 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off

Station managers may have justified under-payment on the basis they were “caring” for workers through providing scant food, clothing and accommodation.

Governments, meanwhile, “withheld” income – often putting money into trust funds that Indigenous people were unable to access. The Queensland government’s $190 million offer is to settle a class action claim for it misappropriating such trust funds.

The fact Indigenous people were vulnerable to such exploitation for decades was made possible by an intricate legislative regime that gave the state expansive powers over their lives. In all states and territories, Aboriginal Protection Acts gave the government officials the power to control the money earned by Indigenous workers.

In Queensland, historian Rosalind Kidd has estimated that 4,500 to 5,500 Indigenous pastoral workers may have lost wage entitlements worth more than $500 million between 1920 and 1968.

Redress schemes

There have been redress schemes in Western Australia, Queensland and New South Wales.

The Queensland government set up the first redress scheme in 2002. It set aside $55.6 million to compensate any individuals who could supply documentary evidence their wages or savings were taken by the Queensland government. If they could do so – and there was a deadline of 2006 on claims – the scheme provided an ex gratia payment of $2,000 to $4,000.

These conditions set a high bar, and $21 million went unclaimed.

Western Australia established its scheme in 2012. It also involved a small ex gratia payment ($2,000) with a limited window to make claims. Claimants called the scheme insulting and mean-spirited. The ABC reported a source that said state treasury officials agreed individuals were owed as much as $78,000, and the government kept the work of its stolen wages taskforce quiet for years, waiting for potential claimants to die.

In distinction to these two schemes, the NSW Trust Funds Repayment Scheme (2006 and 2010) matched the wages withheld in trust funds between 1900 and 1969. It paid $3,521 for every $100 owed, or an $11,000 lump sum where the amount could not be established. This was the closest model to a reparations scheme, though also inhibited by bureaucratic requirements and time limitations.

Due to the limitations of all these state redress schemes, in 2006 a Senate Inquiry into Stolen Wages recommended a national scheme. But no federal government since has acted on this recommendation.

Legal claims

Stolen wages claimants have taken their cases to court in Western Australia, New South Wales and Queensland – but it is only in Queensland that they have had some success.

Read more: Australia's stolen wages: one woman's quest for compensation

One of those is the case of James Stanley Baird, who sued the Queensland government for withheld wages on the basis that paying under-award wages to Indigenous workers was in breach of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. The state government compensated Baird and other plaintiffs the difference owed to them in damages and provided an apology.

Implications

The current settlement is based on a legal claim that the Queensland government breached its duty as a trustee and fiduciary in not paying out wages that were held in trust. The outcome is the most significant repayment for stolen wages plaintiffs in Australian history. Yet the benefits may be confined.

First, in Queensland there is a rich archive of documents (substantially unearthed and analysed by historian Rosalind Kidd) to prove the government misappropriated funds. Such a record may not exist elsewhere.

Second, the settlement only applies to wages placed in “trust accounts”. It has no implications for wages denied to Indigenous workers in other ways, such as by private employers who booked down wages or otherwise refused to pay.

For justice for all wronged Indigenous workers, there needs to be broad-based reparations for stolen wages. This requires truth commissions and a commitment by governments and anyone else that profited from that theft to restore what is owed.

Authors: Thalia Anthony, Associate Professor in Law, University of Technology Sydney