It's hard to find out who Labor's dividend imputation policy will hit, but it is possible, and it isn't the poor

- Written by Elizabeth Savage, Professor of Health Economics, University of Technology Sydney

Labor’s proposal to end cash refunds of unused dividend imputation credits is highly targeted.

It certainly doesn’t apply to age pensioners, even part pensioners, courtesy of Labor’s Pensioner Guarantee.

Self managed super funds set up by pensioners before the announcement are also exempt. Nonetheless it is likely that some pensioners will set up self-managed accounts in full knowledge of Labor’s proposal (the Treasury is reported expect 3,000 to 5,000 per year) which is where the Coalition’s claim that 50,000 pensioners will be affected come’s from. It’s 50,000 over a decade.

Australia has 2.5 million age pensioners.

Charities and not-for-profit organisations would also be exempt and would continue to receive cash refunds of tax paid by companies that paid them dividends.

Labor says the remaining cash refunds come at a significant cost (about A$5 billion per year), that they benefit wealthier people and that the money could be better spent on those less well off.

How did it come to this?

A Labor idea, extended by Howard

Dividend imputation was introduced by the Labor Party as part of the treasurer Paul Keating’s tax reforms in 1987. It allowed taxpayers who owned shares and received dividends to use the tax already paid by the company as a credit against their income tax bill.

In 2001, the Howard government extended it by allowing taxpayers whose dividend credits were larger than the income tax they owed to receive the excess amount in cash. This practice is unique internationally, not least because it can allow company profits to escape tax.

Then in a surprise move in 2006, the Howard government’s penultimate budget made superannuation income tax free for most people aged 60 and over.

It had earlier lifted the tax-free threshold for retirees, meaning many were unlikely to pay tax and be eligible for imputation cheques even before their super income was made tax free. Many more became eligible afterwards.

It’s hard to tell who benefits…

As part of the move to make super income tax free, superannuants were no longer required to declare their superannuation income to the Tax Office, making it hard to tell how well off those receiving imputation cheques really were.

But the Tax Office has released to researchers a series of confidentialised files of individual income tax returns that provide clues.

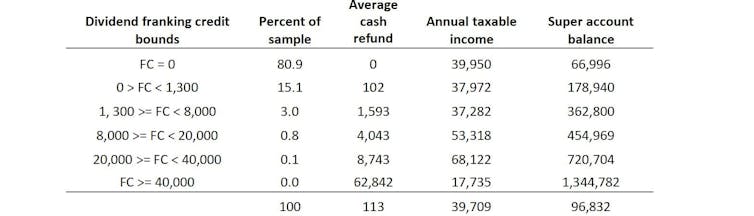

The 2% sample of all taxpayers in 2015-2016 contains 269,639 individual records. I’ve focused on those with taxable incomes of less than A$87,000 (222,083 records) because they are the ones likely to receive cash refunds. I’ve excluded those who receive any government pension or allowance as they are unaffected by Labor’s policy, leaving 190,146 records.

The best measure of these people’s wealth in the data is their total superannuation account balances which the Tax Office collects from member contribution statements.

…although it can be done

Calculating refunds using tax bands and rules, I find that of the people with taxable incomes less than A$87,000 and with no pension income, 81% have no franking credits and receive no refund cheques. Their average taxable income is just below A$40,000 and their average superannuation balance is just below A$67,000.

A further 15% receive credits of less than A$1,300. Their average refund is A$102. Their average taxable income is also below A$40,000 and their average superannuation balance is almost A$179,000.

Of the 3% of individuals with credits between A$1,300 and A$8,000, the average cash refund is A$1,593. The average taxable income for the group is just over A$37,000 and the average superannuation balance is about A$363,000.

Of the 0.8% of individuals with credits between A$8,000 and A$20,000, the average cash refund is A$4,043. The average taxable income for the group is just over A$53,000 and the average superannuation balance is almost A$455,000.

Elizabeth Savage/ATO 2015-16 unit file

Of the 0.1% of individuals with credits between A$20,000 and A$40,000, the average cash refund is A$8,743. The average taxable income for the group is just over A$68,000 and the average superannuation balance is just under A$721,000.

For the top group who have credits in excess of A$40,000, the average cash refund is almost A$63,000, over A$1,200 a week. The average taxable income for the group is the lowest of all groups at A$17,735, falling below the lowest income tax threshold. Almost half (45%) have no taxable income. Their average superannuation balance is A$1,344,782.

It’s the wealthiest who benefit the most

The results tell a clear story.

The largest average benefits are paid to the wealthiest group.

Their wealth measured by superannuation account balance is 20 times that of the group that receives no cash refund. Their superannuation wealth is 76 times their taxable income.

It is misleading it is to use their taxable income as a measure of their well-being.

Read more:

Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation? And what's 'retiree tax'?

Elizabeth Savage/ATO 2015-16 unit file

Of the 0.1% of individuals with credits between A$20,000 and A$40,000, the average cash refund is A$8,743. The average taxable income for the group is just over A$68,000 and the average superannuation balance is just under A$721,000.

For the top group who have credits in excess of A$40,000, the average cash refund is almost A$63,000, over A$1,200 a week. The average taxable income for the group is the lowest of all groups at A$17,735, falling below the lowest income tax threshold. Almost half (45%) have no taxable income. Their average superannuation balance is A$1,344,782.

It’s the wealthiest who benefit the most

The results tell a clear story.

The largest average benefits are paid to the wealthiest group.

Their wealth measured by superannuation account balance is 20 times that of the group that receives no cash refund. Their superannuation wealth is 76 times their taxable income.

It is misleading it is to use their taxable income as a measure of their well-being.

Read more:

Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation? And what's 'retiree tax'?

Authors: Elizabeth Savage, Professor of Health Economics, University of Technology Sydney