Dog whistles, regional visas and wage theft – immigration policy is again an election issue

- Written by Jock Collins, Professor of Social Economics, UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney

This article is part of a series examining the Coalition government’s record on key issues while in power and what Labor is promising if it wins the 2019 federal election.

Immigration policy will be a major issue in the 2019 federal election. We know this because immigration has featured significantly at every Australian election since the 2001 “children overboard” election.

David Marr and Marian Wilkinson argued in their 2003 book, Dark Victory, that willingness to play the race card in relation to boat people was a decisive factor in John Howard’s election victory. For Tony Abbott, “Stop the boats” was a major campaign theme when the Coalition won back government in the 2013 election. The current prime minister, Scott Morrison, rose to prominence as Abbott’s unyielding immigration minister who stopped the boats.

Read more: Australian politics explainer: the MV Tampa and the transformation of asylum-seeker policy

While the events of Christchurch may have cramped the opportunity for the Coalition to run hard on fear, promising to be tough on borders and tough on (Muslim) terrorism, the dog-whistle politics on the issue of refugees and asylum seekers will be there for those wanting to hear it.

For Labor these policy issues have been difficult. It was Kevin Rudd who as PM declared that those arriving by boat would never be settled in Australia, irrespective of the validity of their claims for protection under the UN Refugee Convention. Labor supported efforts to get children out of detention on Manus Island, but doesn’t want to give the conservatives too much space to convincingly advance a “Labor weak on border security” line.

Humanitarian intake is growing

The Coalition governments of Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison have in fact increased Australia’s annual humanitarian intake significantly. The number has risen from just over 13,750 to more than 18,000 – though the government has not loudly broadcast this fact.

In addition, Abbott in 2015 announced a one-off intake of 12,000 Syrian conflict refugees. Most of them arrived in 2017, effectively doubling the annual refugee intake in that year.

Australia – and the refugees – coped well, demonstrating the nation’s capacity to significantly increase refugee intakes. Our research with newly arrived Syrian, Iraqi and Afghan refugee families suggests they are settling well in Australia, receiving a warm welcome from locals in the cities and regional centres. Employment and family reunification are their key worries.

Read more: Refugees are integrating just fine in regional Australia

Labor’s shadow immigration minister, Shayne Neumann, has flagged a new temporary sponsored visa for the parents of migrants. Unlike the current visa, it does not have a cap and it might assist refugees to get their parents to Australia.

Labor has announced it will increase the annual humanitarian intake of refugees to 27,000 by 2025. It will also abolish Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs). These visas provide boat arrivals who are found to be refugees the right to stay for only three years with work and study rights and access to Centrelink payments. As Labor argues, this places them “in a permanent state of limbo”.

The Coalition parties have not announced their policy intentions in relation to humanitarian intakes or the rights of asylum seekers, including those who arrived by boat.

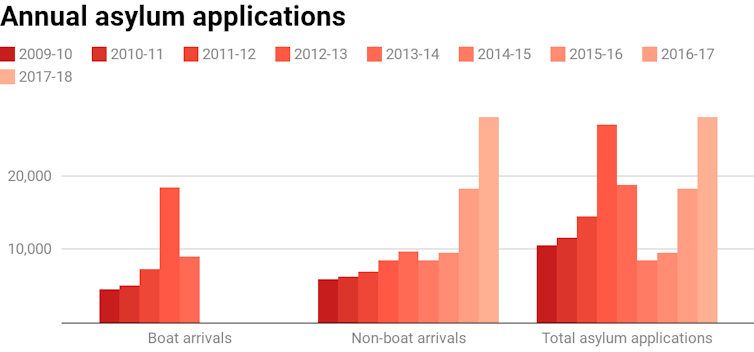

At a time when Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton scans the horizon for new boat arrivals, record number of asylum seekers are arriving by plane under tourist visas. In 2013-14, there were 18,718 asylum applications, including 9,072 boat arrivals. This had increased to 27,931 asylum applications, with no boat arrivals, by 2017-18.

Department of Home Affairs

Each year the Australia government sets the permanent immigration targets. Until recently this was set at 190,00. In practice just 162,000 immigrants have been admitted over the past year or so.

A token cut and 2 new visas

In this context Prime Minister Morrison’s announcement that the permanent immigration target will be cut to 160,000 is really no change in immigration policy. There is nothing to see here if you dismiss the need to be loudly anti-immigration in the current populist political climate.

Read more:

Government's population plan is more about maximising 'win-wins' than cutting numbers

The announcement is linked to congestion-busting in the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne. It is accompanied by the introduction of two new visa pathways – the Skilled Work Regional (Provisional) Visa and the Skilled Employer Sponsored Regional (Provisional) Visa – for skilled migrants to live and work in regional areas for five years.

These visas offer the carrot of permanent residency at the end of three years to attract new immigrants to regional Australia. In addition, the budget announced that scholarships to the tune of $94 million over four years would be available to domestic and international students who study there.

Read more:

Settling migrants in regional areas will need more than a visa to succeed

Temporary migrants exploited

Most immigration policy debates centre on permanent immigration intakes, particularly of humanitarian immigrants and asylum seekers. Yet annual temporary migrant intakes – international students, working holidaymakers and temporary skilled workers – are three times greater than the permanent intake. Over 800,000 temporary migrants were in Australia in June 2018.

One key policy issue is the exploitation of temporary migrant workers. The Turnbull government abolished the 457 temporary skilled migration visa because of increasing reports of abuse and exploitation by employers.

One recent survey of 4,332 temporary migrant workers found “increasing evidence of widespread exploitation of temporary migrant workers, including wage theft”. Half of all temporary migrant workers may be underpaid. About one in three international students and backpackers earned $12 an hour or less – about half the minimum wage.

This issue goes not just to the ethics of maintaining a temporary migration program largely premised on migrant worker exploitation. It also resonates with Labor’s campaign for a living wage and the restoration of penalty rates for workers in response to the low rate of real wage growth in Australia, which constrains consumer demand.

Read more:

Ultra low wage growth isn't accidental. It is the intended outcome of government policies

The 2019-20 federal budget allocated extra funding to the Fair Work Ombudsman to bolster enforcement action against employers who exploit vulnerable workers and announced the National Labour Hire Registration Scheme to target rogue operators in the labour hire industry. However, the research suggests wage theft is widespread in the small business sector, a key target for tax relief in the budget. It is an area of immigration policy that requires considerably more resources and punch.

Department of Home Affairs

Each year the Australia government sets the permanent immigration targets. Until recently this was set at 190,00. In practice just 162,000 immigrants have been admitted over the past year or so.

A token cut and 2 new visas

In this context Prime Minister Morrison’s announcement that the permanent immigration target will be cut to 160,000 is really no change in immigration policy. There is nothing to see here if you dismiss the need to be loudly anti-immigration in the current populist political climate.

Read more:

Government's population plan is more about maximising 'win-wins' than cutting numbers

The announcement is linked to congestion-busting in the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne. It is accompanied by the introduction of two new visa pathways – the Skilled Work Regional (Provisional) Visa and the Skilled Employer Sponsored Regional (Provisional) Visa – for skilled migrants to live and work in regional areas for five years.

These visas offer the carrot of permanent residency at the end of three years to attract new immigrants to regional Australia. In addition, the budget announced that scholarships to the tune of $94 million over four years would be available to domestic and international students who study there.

Read more:

Settling migrants in regional areas will need more than a visa to succeed

Temporary migrants exploited

Most immigration policy debates centre on permanent immigration intakes, particularly of humanitarian immigrants and asylum seekers. Yet annual temporary migrant intakes – international students, working holidaymakers and temporary skilled workers – are three times greater than the permanent intake. Over 800,000 temporary migrants were in Australia in June 2018.

One key policy issue is the exploitation of temporary migrant workers. The Turnbull government abolished the 457 temporary skilled migration visa because of increasing reports of abuse and exploitation by employers.

One recent survey of 4,332 temporary migrant workers found “increasing evidence of widespread exploitation of temporary migrant workers, including wage theft”. Half of all temporary migrant workers may be underpaid. About one in three international students and backpackers earned $12 an hour or less – about half the minimum wage.

This issue goes not just to the ethics of maintaining a temporary migration program largely premised on migrant worker exploitation. It also resonates with Labor’s campaign for a living wage and the restoration of penalty rates for workers in response to the low rate of real wage growth in Australia, which constrains consumer demand.

Read more:

Ultra low wage growth isn't accidental. It is the intended outcome of government policies

The 2019-20 federal budget allocated extra funding to the Fair Work Ombudsman to bolster enforcement action against employers who exploit vulnerable workers and announced the National Labour Hire Registration Scheme to target rogue operators in the labour hire industry. However, the research suggests wage theft is widespread in the small business sector, a key target for tax relief in the budget. It is an area of immigration policy that requires considerably more resources and punch.

Authors: Jock Collins, Professor of Social Economics, UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney