Two ways to fund NSW election promises as property prices crash

- Written by Gareth Bryant, Lecturer in Political Economy, University of Sydney

State elections are always about spending promises, but this time not much is being said about how they will be funded.

Last minute costings on individual announcements tend to rely on the general presumption that the state economy will keep growing and somehow produce the needed revenue.

This is evident in the costings released by the NSW Parliamentary Budget Office, which show that new spending promises from both major parties exceed new revenue promises.

The Labor Party has managed to find some new revenue through increased taxes on luxury cars, boats and vacant properties, while the Coalition has unveiled no new revenue initiatives at all.

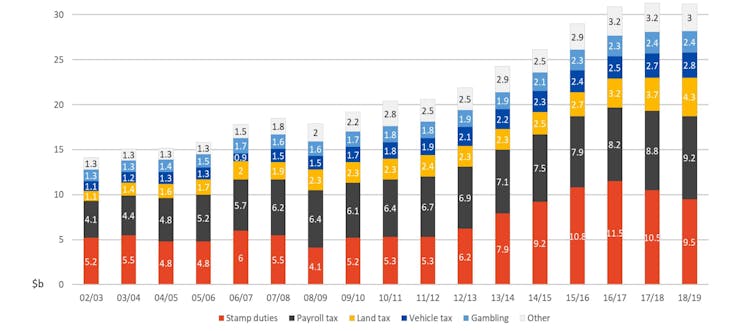

While the property market has been climbing this needn’t have mattered that much. But for the past 20 months Sydney prices have been falling. Projected stamp duty revenues are being repeatedly revised downwards. The latest wipes A$9.5 billion off what was expected at the time of the 2017 budget.

NSW state revenue by type, A$ billion

University of Sydney Policy Lab

Austerity, or an alternative?

It’s looking as if the incoming NSW government will need to moderate spending including spending on essential services and infrastructure, but there might be a way out.

Today, we published a new report for the Sydney Policy Lab outlining two ways in which the NSW government can ready its budget for a post-housing boom economy.

Politicians of all parties tell us that fiscal rules create binding constraints for state governments and they are right.

But there are imaginative ways to strengthen state finances and to interpret those constraints.

Alternative 1: taxing residential land

Although land used for holiday homes and rental properties faces land tax, land used for owner-occupied housing is exempt in NSW, meaning as much as A$1 trillion of land is exempt.

It is a source of wealth – one of the few covered by state tax powers – that the budget can no longer afford to ignore.

Extending NSW land tax to owner-occupied residences with safeguards could fund much of the state’s needed service and infrastructure spending and wind back the outsized reliance on stamp duty.

With so many people locked out of home ownership altogether, it would make the tax system fairer.

Alternative 2: redefining ‘investment’

Under NSW budget rules spending on services is defined as cost that needs to be matched by immediate revenue. Spending on infrastructure, often on infrastructure which will later be privatised, is defined as an investment, meaning it doens’t have to be matched by immediate revenue.

It is why there is talk about a squeeze on services in the midst of record spending on infrastructure.

There’s room to change those definitions.

While there are good macroeconomic and budgetary reasons to differentiate day to day spending from investments, much of what is defined as day to day spending is in fact an investment.

There’s no reason why the state’s power to borrow to invest in infrastructure couldn’t also be used to invest in public services like health and education. With a change of rules, governments could borrow to invest in nurses and teachers at interest rates currently reserved for toll roads.

First steps

A practical starting point would be to connect spending on public services to the savings they create in other parts of the state budget, and account for this as the return on the investment.

As an example, “justice reinvestment” could fund programs aimed at reducing Indigenous incarceration out of the savings those programs would eventually deliver in other areas.

The redefinition would remove the present bias towards programs that build only physical infrastructure that has to be paid for later with tolls or privatisations.

Both ideas could help whichever party or parties form government after Saturday’s election, and help NSW. Without them, budgeting will become more difficult.

Read more:

NSW election likely to be close, and Mark Latham will win an upper house seat

University of Sydney Policy Lab

Austerity, or an alternative?

It’s looking as if the incoming NSW government will need to moderate spending including spending on essential services and infrastructure, but there might be a way out.

Today, we published a new report for the Sydney Policy Lab outlining two ways in which the NSW government can ready its budget for a post-housing boom economy.

Politicians of all parties tell us that fiscal rules create binding constraints for state governments and they are right.

But there are imaginative ways to strengthen state finances and to interpret those constraints.

Alternative 1: taxing residential land

Although land used for holiday homes and rental properties faces land tax, land used for owner-occupied housing is exempt in NSW, meaning as much as A$1 trillion of land is exempt.

It is a source of wealth – one of the few covered by state tax powers – that the budget can no longer afford to ignore.

Extending NSW land tax to owner-occupied residences with safeguards could fund much of the state’s needed service and infrastructure spending and wind back the outsized reliance on stamp duty.

With so many people locked out of home ownership altogether, it would make the tax system fairer.

Alternative 2: redefining ‘investment’

Under NSW budget rules spending on services is defined as cost that needs to be matched by immediate revenue. Spending on infrastructure, often on infrastructure which will later be privatised, is defined as an investment, meaning it doens’t have to be matched by immediate revenue.

It is why there is talk about a squeeze on services in the midst of record spending on infrastructure.

There’s room to change those definitions.

While there are good macroeconomic and budgetary reasons to differentiate day to day spending from investments, much of what is defined as day to day spending is in fact an investment.

There’s no reason why the state’s power to borrow to invest in infrastructure couldn’t also be used to invest in public services like health and education. With a change of rules, governments could borrow to invest in nurses and teachers at interest rates currently reserved for toll roads.

First steps

A practical starting point would be to connect spending on public services to the savings they create in other parts of the state budget, and account for this as the return on the investment.

As an example, “justice reinvestment” could fund programs aimed at reducing Indigenous incarceration out of the savings those programs would eventually deliver in other areas.

The redefinition would remove the present bias towards programs that build only physical infrastructure that has to be paid for later with tolls or privatisations.

Both ideas could help whichever party or parties form government after Saturday’s election, and help NSW. Without them, budgeting will become more difficult.

Read more:

NSW election likely to be close, and Mark Latham will win an upper house seat

Authors: Gareth Bryant, Lecturer in Political Economy, University of Sydney

Read more http://theconversation.com/two-ways-to-fund-nsw-election-promises-as-property-prices-crash-113835