Youth homelessness efforts get a lowly 2 stars from national report card

- Written by David MacKenzie, Associate Professor, Department of Social Science, Swinburne University of Technology

A National Report Card on Youth Homelessness in Australia says government action over the past decade would earn no more than two stars under its four-star rating system. There has been under-investment in most areas. Promises made have been only partially delivered.

The report identifies the lack of a coordinated national strategy as an obstacle to achieving goals that were set a decade ago. The report card will be presented at the National Youth Homelessness Conference being held in Melbourne today and tomorrow.

It’s the first national conference focused solely on homeless youth in Australia in 20 years. It will consider four proposed strategic reforms:

- early intervention

- rapid rehousing

- engagement in education, training and/or employment

- extending state care to the age of 21.

Read more: Homelessness: Australia's shameful story of policy complacency and failure continues

Losing our way even with a roadmap

The report card assesses progress since the 2008 report of the National Youth Commission (NYC) into youth homelessness, the second of two landmark inquiries.

Following the rigorous procedures of the 1989 Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Inquiry into Youth Homelessness headed by Brian Burdekin, the NYC’s independent community inquiry held hearings all over Australia. There were 21 public hearings, 319 people gave evidence, and 92 written submissions were received.

In 2008, Kevin Rudd announced a plan to halve homelessness by 2020.

Dean Lewins/AAP

In 2008, Kevin Rudd announced a plan to halve homelessness by 2020.

Dean Lewins/AAP

The inquiry’s 400-page report, Australia’s Homeless Youth, made 80 recommendations and included a widely publicised ten-point Roadmap for Youth Homelessness. The NYC argued that implementing this roadmap could transform the face of youth homelessness in Australia.

In December 2008, following this report, the federal government released a white paper, The Road Home: A National Approach to Reducing Homelessness. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a bold public commitment to halve homelessness by 2020. This involved three key policy strategies:

- “turning off the tap” – early intervention

- “improving and expanding services”

- “breaking the cycle”.

Read more: New homelessness report shows the cost of waiting for early intervention

How was the report card compiled?

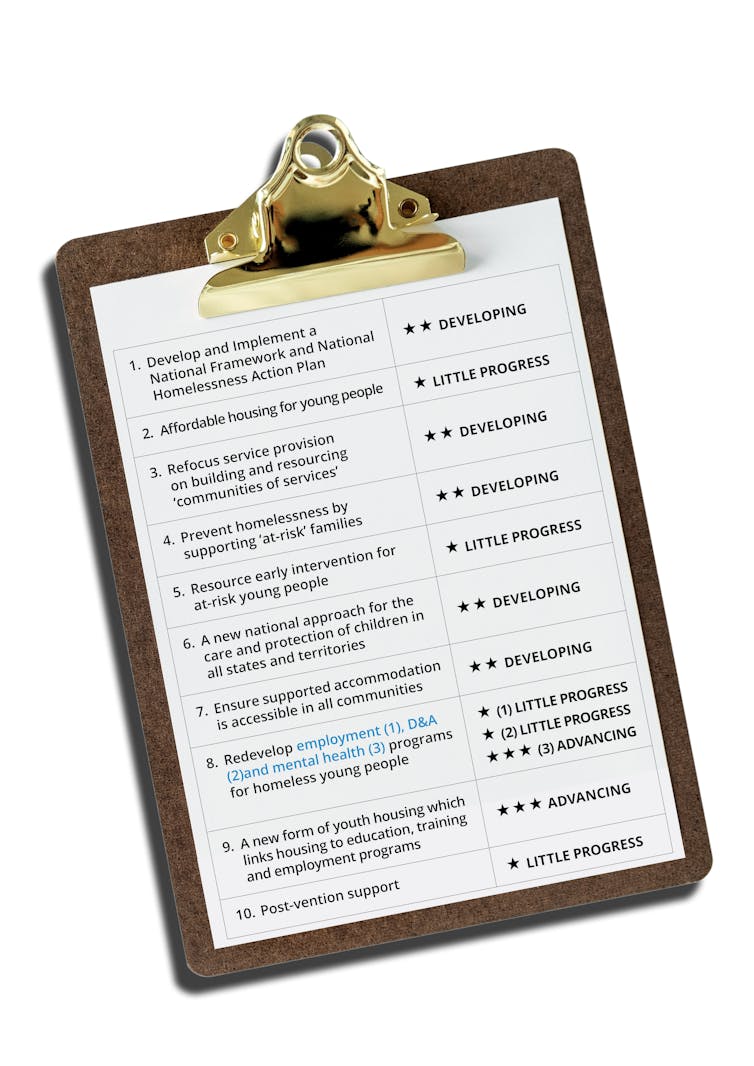

The report card references the ten points of the NYC roadmap. It is a review of responses to youth homelessness over the past decade from a national perspective, and of what still needs to be done.

The 2008 white paper and all subsequent state and territory plans and strategy documents were systematically reviewed against information about what has been done for young people.

Progress under each point was rated using a four-star assessment. Experts and experienced leaders in the various areas then reviewed the preliminary assessments to finalise the ratings.

The National Report Card on Youth Homelessness ratings.

Author provided

The National Report Card on Youth Homelessness ratings.

Author provided

So what happened to the roadmap?

After the white paper, work began on a national strategy to tackle homelessness, but that project was shelved. The states and territories have issued their own plans and strategies, which are, despite some common features, somewhat divergent. The overall national response to homelessness would be hugely strengthened by working to an agreed national strategy like in other high-priority social policy areas.

The roadmap highlighted affordable housing for young people as a priority. This need has hardly been addressed. Young people make up a significant proportion of the homeless population, but they are only 2.9% of tenants in social housing.

Read more: Homeless numbers will keep rising until governments change course on housing

Domestic and family violence is a known cause of homelessness. Only in recent years has there been a significant effort to make this a high social policy priority. A recent increase in funding for a range of services and initiatives is promising but overdue.

The white paper proposed “turning off the tap”, or early intervention, but little has been accomplished. More Australians seek help from homelessness services now than in 2008. This is arguably the single biggest policy failure. An early proposal to expand Reconnect, the early intervention program that has existed since 1997, came to nothing.

Some effort has been made to reform state care and protection, especially the inadequate support for young people leaving care at 18. They are particularly vulnerable to homelessness. The idea of extending state care to at least 21 years of age is not new, nevertheless it is still not well resourced nor securely established nationally.

Read more: Why children in institutional care may be worse off now than they were in the 19th century

Some repair and expansion of the crisis system of homelessness services has been achieved. However, many communities complain they do not have even basic crisis capacity.

The roadmap called for improvement of specialist services for homeless youth such as mental health, drug and alcohol services, and employment services. Little progress has been made on drug and alcohol and employment services. Youth-specific mental health services is one area that has had significant development.

The roadmap also called for a new form of housing that linked supported accommodation with education, training and support into employment. These were foyers and foyer-like facilities modelled largely on the UK foyers. Over a decade, some 15 foyers have been developed in Australia. This can be acknowledged as an achievement.

Lastly, the roadmap argued that support after homelessness (“post-vention”) is important for young people. The passage to independence should not simply be expected, but rather they need extended support (the kind of support most families provide their children) to “break the cycle” of homelessness. In policy terms, Australia has come late to this understanding and little has been achieved on this issue in the past decade.

In making an overall assessment of progress since the NYC roadmap, the report card acknowledges some positive initiatives and progress but also neglect and underachievement. The existing crisis-focused service systems are not reducing youth homelessness; proven early intervention approaches remain critically underfunded and underdeveloped. What has been done, or rather not done, over the past decade continues to fail young people who are at risk of homelessness or experiencing homelessness.

Overall, the report card gives a two-star rating – “developing – some progress under way” – to efforts to reduce youth homelessness over the past decade. As a nation, we cannot be satisfied with a below-average response to youth homelessness. The next decade needs to be a very different story.

Authors: David MacKenzie, Associate Professor, Department of Social Science, Swinburne University of Technology