The end of uncertainty? How the 2019 federal election might bring stability at last to Australian politics

- Written by Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This is part of a major series called Advancing Australia, in which leading academics examine the key issues facing Australia in the lead-up to the 2019 federal election and beyond.

For the second federal election out of three, a change of government is in prospect a long time out from voting day.

Labor has been consistently ahead in the polls, despite its leader, Bill Shorten, remaining unpopular. It’s a repeat of 2013, when the Coalition had polled strongly through the government’s term while opposition leader Tony Abbott’s ratings were low.

But campaigns can count, and upsets can come, as happened dramatically in 1993. Right up to the Saturday of that poll, the Keating Labor government had appeared doomed. But it snatched “the sweetest victory of them all”, thanks to a scare offensive against the Coalition’s radical reform program and a faltering performance by opposition leader John Hewson.

A key point about this next election is that, whichever side wins in May, the incoming government will inherit a bitter, sceptical, exhausted electorate.

Australians are over their politicians. All the stridency, the bad behaviour, the lying, the relentless campaigning, the judgment by opinion poll, and the media shrillness have taken their toll on the tolerance of the average voter.

The election will be fought in this climate of unprecedented public distrust of politics and cynicism about its practitioners.

This disillusionment has been turbo-charged by the bipartisan cannibalism that’s toppled multiple prime ministers in a remarkably short period.

If Labor wins, polling analyst John Stirton says:

… it will be the second change of government in a row that will be a negative change rather than a positive change. Negative in the sense that voters may once again elect an unpopular opposition leader, with their desire to get rid of a poorly performing incumbent government outweighing any concerns they may have about the opposition that will replace it.

The public sullenness will make the task of the next government harder, whether Labor or Coalition.

Contrast the mood in 1983, when Labor’s Bob Hawke was given power by voters who had not only wanted to embrace him personally, but felt more trust towards leaders generally than today. Though it wasn’t smooth sailing, this helped the Hawke government undertake major, difficult reforms. He was even afforded a degree of tolerance when he broke some promises.

In 2007, Australians were also in a relatively positive frame of mind when they turned to Kevin Rudd. Since then, the national mood has gone downhill.

Labor went through self-imposed hell between 2010 and 2013, set off by the ill-judged 2010 dumping of Rudd. But out of office it recovered remarkably quickly.

Labor’s bold ‘big target’ approach

As the opposition shaped up over the past two terms, it has made relatively few major mistakes (Shorten’s boast that his MPs had no problems under Section 44 of the Constitution was one).

Of course, that assumes being bold and taking big risks with policy doesn’t turn out to be the ultimate mistake.

Labor has eschewed the “small target” approach favoured by John Howard in 1996 and indeed Rudd in 2007.

Its proposed crackdowns on negative gearing and cash refunds for franking credits are designed to maximise its pot of spending money as well as fix flaws in the tax system.

Monash University’s Paul Strangio, an expert on prime ministers, suggests this “policy adventurism” may also have been motivated by Labor’s determination to obtain a positive mandate for government. After all, the rot began for the Abbott government when measures in its 2014 budget were not just harsh but unflagged in opposition.

But Labor’s controversial policies leave it exposed to scare campaigns. Each measure has a significant number of losers, and retirees, especially, are highly sensitive to anything that hits their cash flow.

Border security is one area where Labor has tried to stay as close as possible to the government. But it had little choice but to back the crossbench-initiated legislation facilitating medical transfers from Manus Island and Nauru. Despite Shorten securing “middle ground” amendments, this opened another front for Coalition scare tactics.

Shorten has kept an impressive degree of unity and discipline in his party, despite the obvious ambitions of his rival Anthony Albanese, whose gloved hand was ready to strike if the opposition leader did badly in the July 2018 Super Saturday byelections.

But many questions remain about Shorten. Strangio raises an important one:

While he has been an effective manager of a team in opposition, how will this translate into government – for example, what degree of licence will he give to senior ministers like Chris Bowen?

Coalition its own worst enemy

In contrast to Labor, the Coalition has squandered this parliamentary term – and, for that matter, the one before. Its follies have given the opposition repeated advantages.

After a bad campaign, Malcolm Turnbull had the closest of calls in 2016, being returned with a one-seat majority and a bitterly fractured Liberal Party. A vengeful Abbott led the dissent, determined to inflict revenge for the 2015 coup that had ousted him.

Read more: Grattan on Friday: 2018, the year of governing badly

The Liberals have presented to the public as warring tribes who can’t agree on policy or personnel. Infighting over ideology – especially on energy policy – and leadership climaxed last August with Turnbull’s overthrow and the installation of Scott Morrison, beneficiary of a putsch instigated by Peter Dutton.

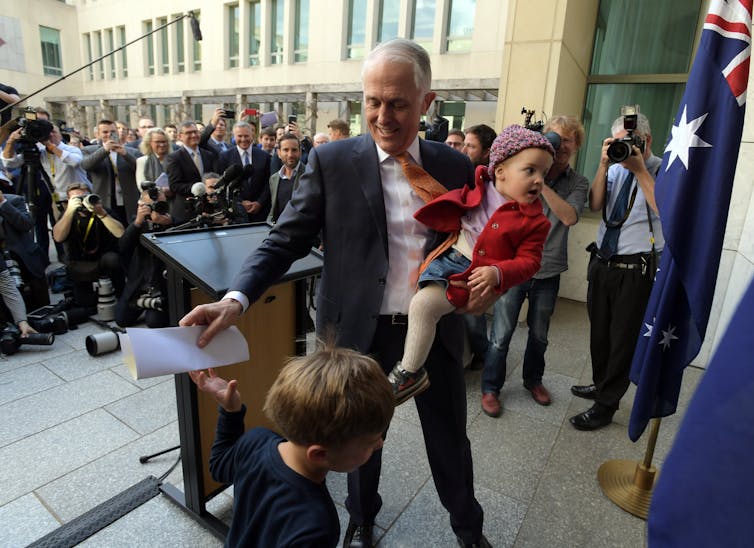

The Coalition’s leadership chaos resulted in Malcolm Turnbull being overthrown in favour of Scott Morrison.

AAP/Sam Mooy

The Coalition’s leadership chaos resulted in Malcolm Turnbull being overthrown in favour of Scott Morrison.

AAP/Sam Mooy

The rise of an aggressive right within the Liberals, and voters’ growing antipathy towards the main parties, have encouraged the popularity of “community” independents.

Those of particular interest in this election are pitching to progressive, right-of-centre voters in heartland conservative seats. Several are backed by strong local citizen movements and are attracting significant funding.

Eyes will focus on whether Zali Steggall can dislodge Abbott in Warringah, and Kerryn Phelps can retain Wentworth, which she won at the byelection following Turnbull’s departure. Julia Banks, the member for the Victorian seat of Chisholm who defected from the Liberals to the crossbench, is making a bid in Flinders against Health Minister Greg Hunt.

In a separate category is former independent MP Rob Oakeshott, part of the balance of power in the Gillard years, who is a threat to the Nationals in the New South Wales seat of Cowper.

While the highly visible push from independent candidates is a feature of this election, and voter angst puts wind in their sails, the House of Representatives’ electoral system will limit their success.

A clear choice of ideologies

This can be seen as a very ideological election. Labor, focusing on “fairness” and “inequality”, is proposing higher taxes. And while careful to keep its program fiscally responsible, it is fanning workers’ discontents and talking up the need to reverse cuts in penalty rates and stimulate wages growth.

The Liberals have struggled, largely because of their internal rifts, to craft a narrative about what they stand for. Nowhere has this been more evident than in energy policy. Rejecting a carbon tax was a successful political battering ram in 2013, but carbon mitigation has turned into a nightmare issue for the Coalition ever since.

An approach that plans to subsidise new power projects and threatens errant energy companies with draconian actions, even divestiture, is an extraordinary landing place for a Liberal government.

The government has doubled down on its “direct action” policy by announcing $2 billion for emission reduction projects over the coming decade from January 2020.

Instead of being accepted as a practical challenge that needs substantial bipartisanship to underpin investment, the Coalition has made energy policy and climate change perhaps the most divisive ideological battleground of contemporary Australian politics.

Business watches with despair: in the past three years, it has been willing to get behind various policies (most recently the National Energy Guarantee) only to see them fall victim to infighting. It is an open question whether the next term will bring any long-term resolution in this most crucial policy area.

We can group the dominant issues in this election under the rubric “economic”.

These range from the government’s boast about economic management and its claim the economy would weaken under Labor, through to stagnant wages growth and Bowen’s assertion that “under the Liberals, the economy is not working for working people”.

The economic umbrella also covers competing income tax cuts and the broader battle over taxation, with the government homing in on Labor’s proposed imposts.

A contest of voter interests

Ian McAllister, director of Australian National University’s long-running Australian Election Study, observes that “the new battleground on tax is people’s assets not their income” – that’s housing (owner plus investment), shares, superannuation. And this is in the context that “Australia has more money in personal assets than any other country of a similar or larger size”.

McAllister also sees this as “almost a generational election”. The millennials in particular “have a lot of pressures on them – they are having difficulties breaking into the housing market, they feel they are not economically prosperous. It affects their level of trust in the political system, in politicians and in democracy.”

Notable, and complicating the campaigning challenges for government and opposition, is the geographical divide, epitomised by Victoria versus Queensland, and requiring varied messages. One insider quips it is “doctors’ wives [progressive Liberal voters who are deserting] versus rednecks”.

After Super Saturday, all the talk in the Coalition was about Queensland, which is loaded with marginal seats. The government’s failure to wrest Longman from Labor fed into the subsequent Dutton assault on Turnbull.

But then came the November 2018 Victorian state election rout of the Liberals. Suddenly the government was looking south, fearing big losses in that state.

In Queensland, the Coalition grapples with fragmentation on the right, with the Hansonites, the Katterites and Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party chipping away at its vote. The Liberals and Nationals are joined in one party in that state; if the Nationals were still separate they might be better placed to contain the problem.

The election matrix is complex. Government and opposition have their national messages, but they must also tailor their appeals to different parts of the country, as well as to each electorate. It’s not quite true that “all politics is local”, but it’s half true and may be becoming more so.

Beyond that, whether in the old-fashioned way (door-knocking) or by using modern data collection and individually tailored, targeted online communications tools, the parties pursue the individual voter.

Normally, a government behind in the polls will have some fat to absorb the first brunt of a swing. Not so this time. “The government has to win seats to survive,” says ABC election analyst Antony Green. Taking into account the redistribution, the government will go into the election with a notional 73 seats, with Labor on 72.

This election is special for the upper house, because the voting changes made by the Turnbull government will operate for the first time in a half-Senate poll. With the seats of 13 crossbenchers (including Greens) in play, Green says they’ll be lucky if half get back.

He predicts a Labor government should have a significantly easier time with the Senate than the current government has had. Indeed, so should a returned Coalition government, “because the crossbench must shrink”.

In search of stability

One of the most important imponderables about the election is this: will it produce more stability?

Remember that apart from the coups, since 2010 we’ve had two hung parliaments, the second resulting from the loss of Wentworth.

On the leadership front, things should be better. Both major parties have responded to the prime ministerial turnover with rule changes that essentially provide that the next PM, whether Shorten or Morrison, will not face an internal challenge during the term (albeit no rule is immutable).

If there is a Coalition victory, it surely could not be anything but a very close result, even a hung parliament. After the first flush of surprised exultation, the fight for the soul of the Liberal Party would likely resume.

If Labor wins with a solid majority, that probably would restore some more general stability – although the tyranny of the opinion polls suggests caution about such a prediction.

Strangio asks:

Will the mantle of office finally secure for Shorten some belated goodwill from the electorate? If not, and voters remain grudging to him and polls precipitously head south for his administration, we may be condemned to yet another period of instability and poor, reactive government.

Some electoral goodwill is necessary for effective, and certainly for reformist, government over the longer term.

But if voter disillusionment and distrust have become so heavily ingrained in the electorate’s psyche, it is hard to either prescribe or expect a cure.

Authors: Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra