Barrie Kosky's The Magic Flute is a contemporary spectacle, despite the opera's outdated attitudes

- Written by Vivienne Glance, Hon Research Fellow in Poetry and Theatre studies, University of Western Australia

Review: The Magic Flute, Perth Festival 2019

As the overture ends, the red curtains at His Majesty’s Theatre rise to reveal a flat, white floor-to-ceiling wall. This suddenly transforms to show a young man being chased through a forest by a red dragon-like serpent. But the performer on stage is not really running; he is standing still, with a pair of comic, animated legs projected onto a white board from his waist down.

This opening sequence sets the tone for the Komische Oper Berlin’s cinematic production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

Barrie Kosky and Suzanne Andrade’s interpretation of this popular and oft-performed opera (first performed in 1791) is unlike any previous production staged in Australia. Teaming up with animator Paul Barrit and co-director Andrade, both from UK theatre company 1927, Kosky’s version captures the vaudeville anarchy of the original opera.

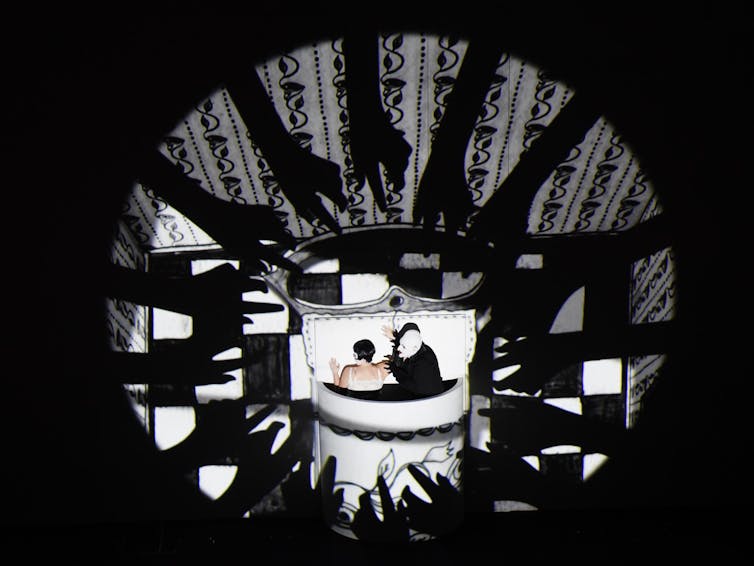

The singers inhabit a world filled with monsters, magic, revenge, death, love and lust: a perfect fairy tale scenario. The colour-filled era of 1930s German expressionism and the black and white of the popular silent movies of the 1920s provide consistent design motifs for Barritt’s exquisite, hand-drawn animation.

Paul Barritt’s animation draws upon the aesthetics of German expressionism and silent films of the 1920s.

Toni Wilkinson

Paul Barritt’s animation draws upon the aesthetics of German expressionism and silent films of the 1920s.

Toni Wilkinson

German expressionism emphasised the artist’s feelings over reality, and the more fantastical elements of this opera are well-suited to this style, full of bright colours and simple shapes. Blending this with live action and live music (Western Australian Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Hendrik Vestmann) makes the production quite unique. The performers add to this with stylistic movements straight out of silent film, including wide-eyes and exaggerated tip-toeing steps.

The opera’s protaganist, the young prince Tamino, was sympathetically portrayed by Aaron Blake on opening night (most roles are rotated between two performers). He has a compelling presence on stage, and there is a wonderful sequence where his soaring tenor voice is accompanied by animated creatures from the constellations, charmed by his magic flute.

Tamino’s unlikely companion, the bird-catcher, Papageno, was performed in a canary-yellow suit by Joan Martín-Royo. He is wonderfully entertaining, and shows a versatile emotional range moving from alcoholic euphoria through suicidal despair, to undying, stuttering love. The duet when Papageno is finally together with his love Papagena, played as a stockinged chorus girl by Talya Lieberman, is delightful and made even funnier by the exaggerated animation.

No Magic Flute review would be complete without comment on the Queen of the Night and her rendition of the famous aria, “Der Hölle Rache” (Hell’s Revenge). Kosky and Andrade depict the queen as a spider with coloratura soprano, Christina Poulitsi, placed high up on a platform.

The Queen of the Night is depicted as a spider in Barrie Kosky’s production.While the screen is filled with her prodding, spindly legs, the singer is confined in a body sleeve. Nonetheless, she displays her range and virtuosity with a note-perfect performance.

The woman Tamino falls desperately in love with is Pamina, sung beautifully by Soprano Iwona Sobotka on opening night. She played the heroine-in-need-of-rescue to perfection, but despite the sexism spouted by some characters, Pamina showed courage, determination and integrity.

That said, she does fall into despair when she believes she is no longer loved by Tamino, and Sobotka sings Pamina’s aria with great feeling as she contemplates suicide.

Pamina and Papageno in The Magic Flute.

Toni Wilkinson

Pamina and Papageno in The Magic Flute.

Toni Wilkinson

Indeed, The Magic Flute is a problematic work when to comes to the portrayal of women. For example, the Three Ladies who serve the Queen of the Night start complaining about each other in the first scene.

Male characters make generalised statements about women’s failings: when Pamino’s captor, Sarastro states that “women do little but talk a lot” there was an audible groan from the audience; and Papageno dreams of catching a thousand women by bewitching them with his pipes.

However, these attitudes are countered by the suggestion that if a woman has no fear of death or night, then she is worthy to enter Sarastro’s Temple. Pamina earns this respect from the Temple knights by accompanying Tamino on his trail of Fire and Water, wonderfully realised through animation with images of skeletons in the bowels of the earth and deep-ocean creatures.

The original opera also has racist elements, with the black slave, Monstatos, depicted as a self-loathing, sexual predator. This production side-steps this by making this character look like Nosferatu from the 1922 silent horror movie. He is played so villainously by Ivan Tursic that he provoked pantomime “boos” during his curtain call.

Monstatos is portrayed villainously by Ivan Tursic.

Toni Wilkinson

Monstatos is portrayed villainously by Ivan Tursic.

Toni Wilkinson

Despite the historical problems with this 200-year-old opera, Kosky and Andrade have created a visual spectacle that, along with the fine performances, provides an enjoyable and accessible night of opera.

However, there are limitations to the staging. The flat wall across the stage onto which the amazing animation is projected includes five access doors placed high up, each with one-person-sized platforms in front. Another door is in the centre at the stage level. This means that characters can only be positioned across the front of the stage or on these platforms.

Efforts are made to break up the staging by having the characters bring on hand-held projector screens, but at times it felt a little repetitive. Yet that is a minor quibble. With a packed house on opening night, it seems audiences will never tire of this fantastical tale.

The Magic Flute is playing at Perth Festival until February 23.

Authors: Vivienne Glance, Hon Research Fellow in Poetry and Theatre studies, University of Western Australia