What are we teaching in business schools? The royal commission's challenge to amoral theory

- Written by Walter Jarvis, Director, UTS Master of Management; Lecturer in Managing, Leading & Stewardship, University of Technology Sydney

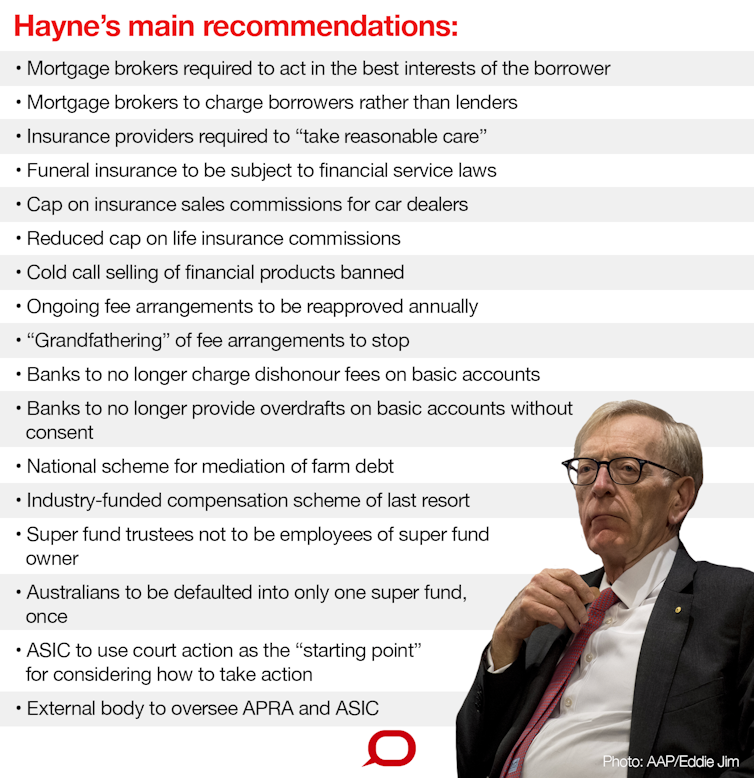

The banking royal commission has seen spectacular resignations, calls for changes in the law, and calls for cultural change within banks.

But what about changes in education, which is where much of what’s wrong begins?

Business schools teach the people who will one day be the managers and leaders who run banks and other financial institutions.

They have had a hand in driving much of what came before the commission – the prioritisation of profit (ends) over how people are treated (means).

They’ve taught the theories that have led to obscene executive compensation and unprecedented earnings inequality.

They are arguably a “force for evil”, purveyors of “immoral profit strategies”.

One professor has suggested the only way to fix them is to bulldoze them.

Amorality as a ticket to respect

They’ve become like this – probably amoral rather than immoral – in order to seem values-free, like the physical sciences such as chemistry and physics that are accorded so much respect.

But what they have taught hasn’t been values-free. Business schools have taught that there’s an imperative to maximise profits, almost no matter what. It may have even become self-fulfilling, freeing students from a sense of moral responsibility.

The idea comes from the “homo economicus” strand of economic theory, much challenged in economics itself. Managers, shareholders, customers and everyone else are said to be selfish maximisers of personal wealth and power with little regard for honesty and decency.

Because managers’ incentives are linked to the value of their company’s shares (shareholder value primacy), they are said to put shareholder value above everything else.

There’s an alternative

There’s another way, and it’s gaining ground. More and more universities are teaching stakeholder theory, in which corporations exist to create value for multiple stakeholders such as customers, employees, suppliers, communities and ecologies, rather than only shareholders.

At the University of Technology Sydney we are also teaching a course entitled Managing, Leading and Stewardship in which students learn what it’s like to be in “morally unequal” situations. We invite them to explore organisational and management practices more aligned to moral equality; including cooperatives, commons, and employee ownership.

They are introduced to the well recognised German-based “enterprise” or mitbestimmung model, in which workers are elected as directors, taking between one-third and one-half of all supervisory board positions.

It is a governance model in which labour (workers) and capital (management) are not just deemed equally important but are held jointly responsible for the long-term well-being of the enterprise. It has operated in Germany and other parts of Europe for more than 70 years.

Sometimes it is known as the “two boards” model (a supervisory board and a management board). The recently-declared US 2020 Democrat presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has incorporated it into in her Accountable Capitalism policy.

It’s a dignity threshold

UTS and business schools in the United States are also developing courses that ask students to role play decisions with ethical dilemmas.

At the base of these courses is the idea of a “dignity threshold”, the minimum level of respect that should be accorded to people affected by and engaged in a business – not only those directly involved (customers and employees), but also those indirectly affected, such as local schools, hospitals, and government agencies.

“Dignity” means being treated as the moral equal of anyone else, a definition outlined in the book Humanity without Dignity by Andrea Sangiovanni.

At the royal commission, it became clear that many of those affected by the misbehaviour of banks and related institutions could sense that they weren’t being treated as morally equal. They were dehumanised and treated as means to do what many witnesses from within the sector said was their sole purpose: making money.

If we want our future managers and leaders to stop engaging in such conduct, we will need to start teaching them about how to be morally as well as financially accountable.

It is what publicly funded universities are for – to project and enhance society’s values.

The legitimacy of business (and business schools) hinges on ensuring they do it.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Authors: Walter Jarvis, Director, UTS Master of Management; Lecturer in Managing, Leading & Stewardship, University of Technology Sydney