Why visual illusions appear in everyday objects – from nature to architecture

- Written by Kim Ransley, Postdoctoral researcher, University of Sydney

Optical illusions are cleverly designed to distort reality, but did you know that the same distortions occur frequently in everyday life?

Our ability to see involves the brain moulding raw sensory data into a refined form. Some of the refinements are deliberate – they’re designed to help us survive.

But the process also requires a surprising amount of guess work. And while our brains have evolved to guess right most of the time, certain patterns regularly trip it up. That’s when we might see an optical illusion.

These patterns can have the same illusive effect whether encountered in a book of optical illusions, or on your way to the train station.

Read more: Which square is bigger? Honeybees see visual illusions like humans do

Hidden objects

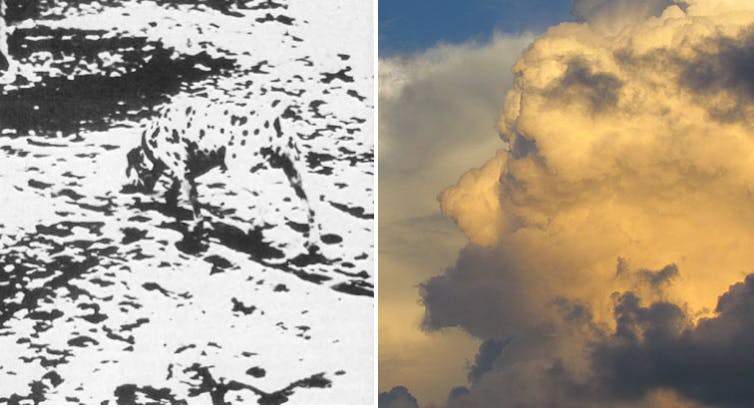

Left: Richard L Gregory. Right: Jim Mullhaupt.

Jim Mullhaupt/flickr

Left: Richard L Gregory. Right: Jim Mullhaupt.

Jim Mullhaupt/flickr

A bunch of random blotches can sometimes be interpreted as complicated visual objects, as shown in the classic illusion on the left. (Don’t see it? Keep looking! You might see a Dalmatian sniffing the ground).

In day to day life, the ability to distinguish objects helps us work out what is around us when parts of the scene are covered or lighting is poor.

But, visual patterns that occur by chance can also trigger the system, causing us to see familiar objects in very strange places – such as the appearance of a face in a cloud (right image).

Distorted dimensions

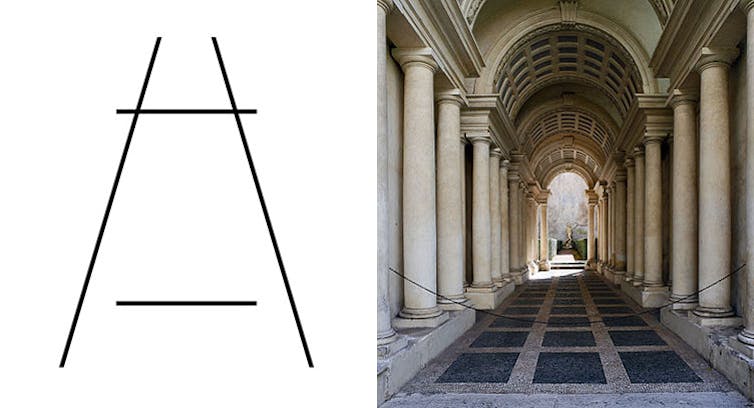

Left: Ponzo Illusion. Right LivioAndronico (2013)

wikimedia commons

Left: Ponzo Illusion. Right LivioAndronico (2013)

wikimedia commons

The two horizontal lines in the Ponzo Illusion (left image) are actually the same length, but to most people, the lower line seems shorter. The illusion works by using converging lines to mimic the appearance of parallel lines extending into the distance (train tracks often give this appearance).

Because the brain interprets the top line as being further away, it judges that the line must be bigger than it actually is, and inflates the appearance of the line accordingly.

Read more: Live in a small place? An interior designer's tips to create the illusion of space

Size and distance are difficult for the brain to work out at the same time – a large ball that is seen from a long way away casts exactly the same raw image as a small ball seen up close. The brain relies on many different cues to work this out, and usually does a pretty good job. But it can make errors when the context is misleading.

This principle has been exploited by designers for centuries now, as seen in this classic example of roman architecture (right image). Here, the ancient designers put a pint-sized statue (60cm tall) at the end of the corridor (9m long) in the Palazzo Spada.

Because we are used to seeing life-size human forms, viewers assume that the statue must be human-sized and a long way away, giving the impression that the hallway is much longer than it actually is.

Slimming stripes

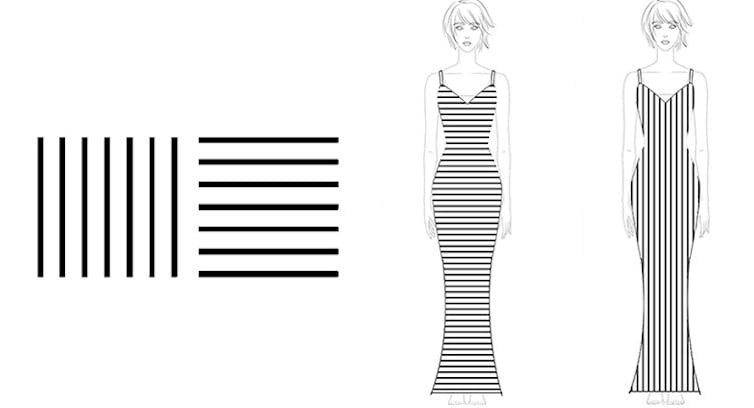

Kim Ransley (2019)

Kim Ransley (2019)

Scientists have long known that objects bearing stripes may appear wider or taller than they really are, though scientists are yet to fully explain why the brain produces this particular distortion.

The Helmholtz illusion (left image) shows this with two squares. Many people report that a square with vertical stripes appears too wide, and a square with horizontal stripes appears too tall.

The effect may work for clothing, too, with a few studies now showing that tops or dresses with horizontal stripes can make the wearer appear slimmer than the same item with vertical stripes (right image).

Unfortunately, a recent study suggests that this effect may rely on the wearer being slim to begin with. The bigger the wearer, the less likely the illusion is to work.

Read more: Three visual illusions that reveal the hidden workings of the brain

As we can see, our experience can differ from reality in many ways. What’s more, it’s likely that the visual distortions we don’t notice far outnumber those that we do.

Understanding the processes used by our brains can allow us to better predict sensory experiences, and use this to build objects with functional advantages and intriguing forms.

Dr Kim Ransley will present these and other illusions as part of the Sydney Design Festival on 8 March 2019

Authors: Kim Ransley, Postdoctoral researcher, University of Sydney