Beware of Pity is beautiful to watch, but clashes with modern sensibilities

- Written by Caroline Wake, Senior Lecturer in Theatre and Performance, UNSW

Review: Beware of Pity, Sydney Festival 2019

Performances in the Roslyn Packer Theatre typically begin when the house lights go down, the stage lights come up, and the audience falls silent. In Beware of Pity, the house lights stay up and the audience is still talking when the seven members of the Schaubühne Berlin ensemble skip lightly onto the stage, assume their positions and stare out at the audience.

It is more akin to the entrance of an orchestra than a theatre ensemble. The audience responds with tentative applause; one actor nods in acknowledgement but the rest continue staring. This soliciting of attention, only to disdain it once it arrives, is central to Beware of Pity.

The play is based on Austrian author Stefan Zweig’s novel of the same name. The book was published on the eve of one war in 1939, and is set on the eve of another in 1914. Don’t let the dates fool you: this is no modernist affair.

Beware of Pity is performed by the Schaubühne ensemble at the Sydney Festival.

Jamie Williams

Beware of Pity is performed by the Schaubühne ensemble at the Sydney Festival.

Jamie Williams

Instead it is closer to a bildungsroman, or coming-of-age novel, that tells the story of the young soldier Anton Hofmiller and his entanglement with, and brief engagement to, Edith Kekesfavla, the daughter of a wealthy baron. Approximately 80 years after the book’s publication, the London-based Complicité and Berlin-based Schaubühne have adapted it for the stage, premiering it in 2015 and touring it since.

Both the novel and the play are told as stories-within-stories that start approximately in the present day – 1937 in the novel and 2013 in the play – before rapidly rewinding to 1914. Rather than disposing of the descriptive passages and focusing on dialogue, as most theatrical adaptations do, this one retains both, with the ensemble alternating between reading the narrative and enacting the events within it.

The events themselves are minor but take on major proportions in the minds of the characters. The catalysing event occurs when Hofmiller (Laurenz Laufenberg, the only actor to play a single role) invites Edith to dance, unaware that she is paralysed from the waist down.

Marie Burchard as Edith and Laurenz Laufenberg as Hofmiller in Beware of Pity.

Jamie Williams

Marie Burchard as Edith and Laurenz Laufenberg as Hofmiller in Beware of Pity.

Jamie Williams

The mortified Hofmiller – Toni to his friends – makes amends by spending a month’s pay on a preposterously large bunch of roses. Edith responds by inviting him to tea and soon he is visiting every day, apparently oblivious to her growing affection for him. It is not until she demands a goodnight kiss with what he perceives to be an unbecoming appetite that he comes to realise what has happened.

Midway through the performance, Beware of Pity goes back in time again, through a story that Edith’s doctor (Johannes Flaschberger) tells Hofmiller. It turns out that Edith’s father is not a baron by birth and obtained his castle by deceiving the woman who inherited it. He pays her vastly less than it is worth, but takes pity when he realises that she has nowhere to go, inviting her to stay on at the castle as his wife.

The doctor’s own marriage is also one of suggested imbalance: he married a former patient of his who is described as “blind and plain”. Is Hofmiller merely the latest in a long line of men who have been tricked into marriage by women manipulating their capacity for pity? Or is it more complicated than that?

The set, costumes and performances in Beware of Pity are all superb.

Jamie Williams

The set, costumes and performances in Beware of Pity are all superb.

Jamie Williams

There is no doubt that the play is out of step with contemporary sensibilities. It would fail the Bechdel Test for its representation of women, the Fries Test for the representation of people with disabilities, and any other test you might care to administer.

Nevertheless, it is beautiful to watch: the set (Anna Fleischle), costumes (Holly Waddington) and performances are all superb. On the night I attended, however, the English surtitles were not well positioned. One screen was too distant while the other was obscured, but hopefully this has since been remedied.

Soft spots and stark slices of light (Paul Anderson) bring the actors in and out of focus, in concert with the sound design (Pete Malkin). The sounds are mostly naturalistic: birds to evoke the garden and amplified footsteps to convey the spaciousness of the castle.

Others are more suggestive, such as when a heartbeat throbs through the space to convey a character’s anxiety, or when the strings and harp of Mahler’s Symphony No 5, Adagietto float through the air.

The actors perform with vigour and precision. Marie Burchard lip-syncs Edith’s lines in a scene with Hofmiller, while Eva Meckbach speaks her dialogue into a microphone. Laufenberg leans forward to hand a photograph to Burchard while another actor downstage places the photographs in front of the camera, sending the live feed to a large screen upstage.

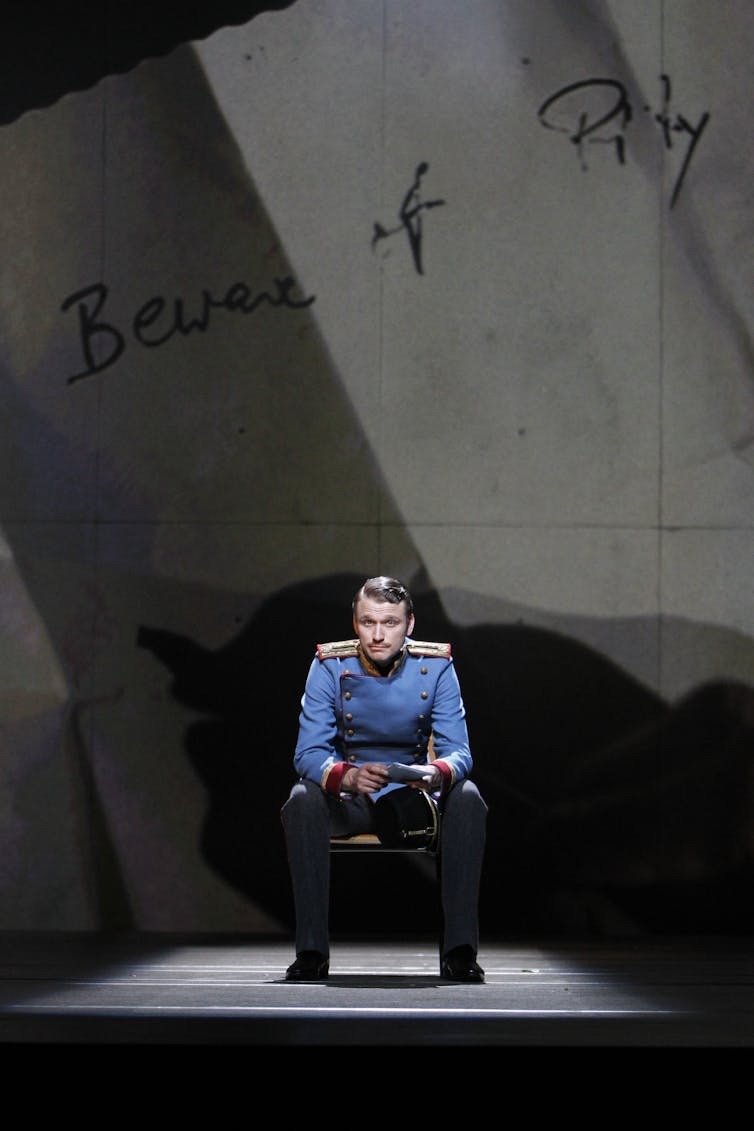

Laurenz Laufenberg as Hofmiller is the only actor in Beware of Pity to play a single role.

Jamie Williams

Laurenz Laufenberg as Hofmiller is the only actor in Beware of Pity to play a single role.

Jamie Williams

The most satisfying moments come when all seven performers and the screens coincide, as when the actors frantically flap their hands as if to clap while the screen displays scores of hands clapping.

Sometimes all this activity makes the performance feel over-engineered, for example when one character mentions black gas and a projection of black gas appears upstage. These moments of over-illustration are not only unsubtle but also untrusting of the audience.

Light and sound work together to bring Beware of Pity to life.

Jamie Williams

Light and sound work together to bring Beware of Pity to life.

Jamie Williams

When not participating in a scene the actors sit, smoke, drink, and watch the action. As this mode of meta-spectatorship – we watch them watching – combines with the story-within-a-story and the marriages-before-the-marriage, Beware of Pity becomes almost too self-reflexive.

Indeed, much of the play seems concerned with “the pleasure of creativity” generally – as Hofmiller puts it – and with theatricality specifically. Edith is described as walking “like a marionette”, while Hofmiller laments his inability to act, or rather to lie, saying “I was not convincing”.

The final scene takes place at a performance of Gluck’s Orpheus, where the elderly Hofmiller glimpses the even more elderly doctor. Why would a military man go to the theatre? To be re-sensitised to suffering and reawaken his sense of pity, or to dull it further and persuade himself that every death is fictional or at least accompanied by an aria?

Both Hofmiller and Beware of Pity seem to want it both ways. Hofmiller wants to confess to a crime but also be forgiven for it. Likewise, Beware of Pity comes to warn us against pity via the medium most closely associated with it. Pity is described as a force of nature throughout the performance: a “poison”, a “surge”, a “double-edged weapon”.

So, yes, beware of pity but even more so beware of those who issue such a warning. Chances are they want that pity for themselves.

Authors: Caroline Wake, Senior Lecturer in Theatre and Performance, UNSW