Desal plants might do less damage to marine environments than we thought

- Written by Graeme Clark, Senior Research Associate in Ecology, UNSW

Millions of people all over the world rely on desalinated water. Closer to home, Australia has desalination plants in Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, the Gold Coast, and many remote and regional locations.

But despite the growing size and number of desalination plants, the environmental impacts are little understood. Our six-year study, published recently in the journal Water Research, looked at the health the marine environment before, during and after the Sydney Desalination Plant was operating.

Read more: Fixing cities' water crises could send our climate targets down the gurgler

Our research tested the effect of pumping and “diffusing” highly concentrated salt water (a byproduct of desalination) back into the ocean.

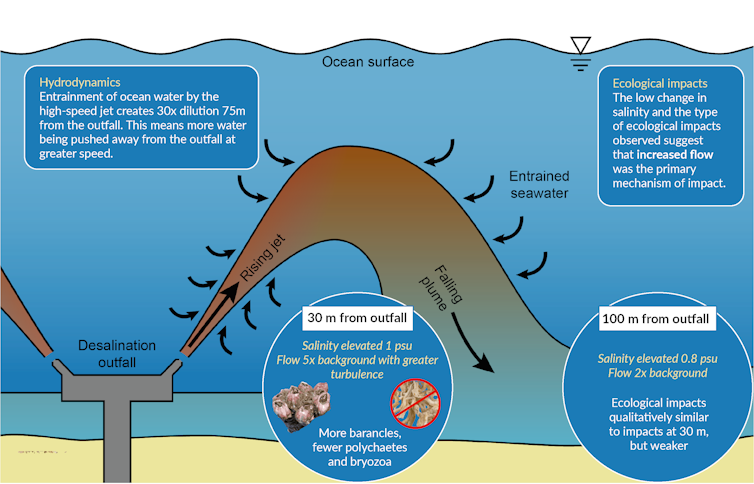

Contrary to our expectation that high salt levels would impact sea creatures, we found that ecological changes were largely confined to an area within 100m of the discharge point, and reduced shortly after the plant was turned off. We also found the changes were likely a result of strong currents created by the outfall jets, rather than high salinity.

Desalination is growing

We examined six underwater locations at about 25m depth over a six-year period during which the plant was under construction, then operating, and then idle. This let us rigorously monitor impacts to and recovery of marine life from the effects of pumping large volumes of hypersaline water back into the ocean. We tested for impacts and recovery at two distances (30m and 100m) from the outfall.

This study provides the first before-and-after test of ecological impacts of desalination brine on marine communities, and a rare insight into mechanisms behind the potential impacts of a growing form of human disturbance.

About 1% of the world’s population now depends on desalinated water for daily use, supplied by almost 20,000 desalination plants that produce more than 90 million cubic meters of water per day.

Increasingly frequent and severe water shortages are projected to accelerate the growth in desalination around the world. By 2025, more than 2.8 billion people in 48 countries are likely to experience water scarcity, with desalination expected to become an increasingly crucial water source for many coastal populations.

Effect of the diffusers

The diffusers that pump concentrated salt water into the ocean at a high velocity (to increase dilution) are so effective that salinity was almost at background levels within 100m of the outfall. However, the diffusion process increased the speed of currents close to the outfall.

This strong current affects species differently, depending on how they settle and feed. Marine species with strong swimming larvae, such as barnacles, can easily settle in high flow and then benefit from faster delivery of food particles. These animals increased in number and size near the outfall. In contrast, species with slow swimming larvae, such as tubeworms, lace corals and sponges, prefer settling and feeding in low current and became less abundant near the outfall.

Therefore, the high-pressure diffusers designed to reduce hypersalinity may have inadvertently caused impacts due to flow. However, these ecological changes may be less concerning than those caused by hypersalinity, as the currents were still within the range that marine communities experience naturally.

Our findings are important, because as drought conditions around the nation worsen and domestic water supplies are coming under strain, desalination is starting to ramp up in eastern and southern Australia.

For instance, water levels at Sydney’s primary dam at Warragamba have dropped to around 65% and the desalination plant is contracted to start supplying drinking water back into the system when dam levels fall below 60%. This plant can potentially double in capacity if needed.

Read more:

Melbourne's desalination plant is just one part of drought-proofing water supply

There is a rapid expansion of the use of desalination, with global capacity increasing by 57% between 2008 and 2013. Our results will help designers and researchers in this area ensure desalination plants minimise their effect on local coastal systems.

Desalination is growing

We examined six underwater locations at about 25m depth over a six-year period during which the plant was under construction, then operating, and then idle. This let us rigorously monitor impacts to and recovery of marine life from the effects of pumping large volumes of hypersaline water back into the ocean. We tested for impacts and recovery at two distances (30m and 100m) from the outfall.

This study provides the first before-and-after test of ecological impacts of desalination brine on marine communities, and a rare insight into mechanisms behind the potential impacts of a growing form of human disturbance.

About 1% of the world’s population now depends on desalinated water for daily use, supplied by almost 20,000 desalination plants that produce more than 90 million cubic meters of water per day.

Increasingly frequent and severe water shortages are projected to accelerate the growth in desalination around the world. By 2025, more than 2.8 billion people in 48 countries are likely to experience water scarcity, with desalination expected to become an increasingly crucial water source for many coastal populations.

Effect of the diffusers

The diffusers that pump concentrated salt water into the ocean at a high velocity (to increase dilution) are so effective that salinity was almost at background levels within 100m of the outfall. However, the diffusion process increased the speed of currents close to the outfall.

This strong current affects species differently, depending on how they settle and feed. Marine species with strong swimming larvae, such as barnacles, can easily settle in high flow and then benefit from faster delivery of food particles. These animals increased in number and size near the outfall. In contrast, species with slow swimming larvae, such as tubeworms, lace corals and sponges, prefer settling and feeding in low current and became less abundant near the outfall.

Therefore, the high-pressure diffusers designed to reduce hypersalinity may have inadvertently caused impacts due to flow. However, these ecological changes may be less concerning than those caused by hypersalinity, as the currents were still within the range that marine communities experience naturally.

Our findings are important, because as drought conditions around the nation worsen and domestic water supplies are coming under strain, desalination is starting to ramp up in eastern and southern Australia.

For instance, water levels at Sydney’s primary dam at Warragamba have dropped to around 65% and the desalination plant is contracted to start supplying drinking water back into the system when dam levels fall below 60%. This plant can potentially double in capacity if needed.

Read more:

Melbourne's desalination plant is just one part of drought-proofing water supply

There is a rapid expansion of the use of desalination, with global capacity increasing by 57% between 2008 and 2013. Our results will help designers and researchers in this area ensure desalination plants minimise their effect on local coastal systems.

Authors: Graeme Clark, Senior Research Associate in Ecology, UNSW