Fewer Australian university students than ever before believe in creationism

- Written by Mike Archer, Professor, Pangea Research Centre, UNSW

Australian university students appear to give far more credit to the science of human evolution and far less to creationism or divine guidance than the previous generation. This is according to our 32-year-long annual survey of first-year biology students at UNSW in Sydney.

Belief among students that God is the ultimate or contributing cause of human origins has steeply declined. It was a majority view in 1986, and now a minority view in 2017. Conversely, the belief that humans evolved without divine involvement of any kind rose steeply over the same period to become the dominant view.

Reasons for these significant changes over time may include increasing access to the web, increasing scientific evidence for evolution, and/or growing scepticism about claims for supernatural miracles of any kind.

What is creationism?

In most Western countries creationism involves belief the Bible, and in particular the Book of Genesis, is a correct and factual account of how the universe and life came into being. Accordingly, their common view is that God created the universe and all kinds of animals and plants within a single seven day week less than 10,000 years ago.

Adam and Eve were constructed on day six of this creation week. God made Adam from dust and Eve from one of Adam’s ribs. Both were placed in the Garden of Eden where they lived alongside, among other things, herbivorous lions (there was no death until Adam sinned, dinosaurs and all other kinds of animals known and unknown, including talking snakes.

Commonly, more than 40% of Americans hold fast to these convictions and refuse to accept that evolution has occurred, let alone that humans evolved over millions of years from other kinds of animals.

In contrast, most people who believe in God but not literal creationism accept that it should be the business of science to research the nature and origin of the natural world, and it should be the business of religion to focus on life’s meaning and purpose.

Most mainstream theists – those who believe in the existence of one or more gods – don’t see a major conflict between their religious beliefs and understanding about the reality of evolution. Accepting that the Genesis account may be an allegory, they see no major problem in accepting the possibility that evolution was God’s method of creation.

The survey

We began a survey of student attitudes in 1986 in order to assess the level of a commitment among incoming students to supernatural explanations for our origins. From 1986 to 2017, every student attending our first-year biology course was invited to complete a one item poll on a strictly anonymous basis.

An average of 530 students a year participated in the survey. The results of the each year’s survey – and those of all previous years – were openly presented to and discussed with that year’s class in the following lecture.

Each student was handed a slip of paper as they walked into the classroom and was asked to circle one of the following four options, the one they agreed with most:

God created people (Homo sapiens) pretty much in their present form at some time within the last 10,000 years (literal creationism)

people developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God guided the whole process, including our development (creationism through evolution)

people developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life. God had no part in this process (evolution)

I honestly have no opinion about this matter.

This wording closely adheres to that commonly used for many years in Gallop polls conducted in the US.

The results

We found the percentage of our students who chose the literal creationism option has been consistently small (about four times smaller than the percentage commonly endorsing this option in the US). In 1986, only 10% of the class believed in creationism. This slowly declined by more than 50% to less than 5% in 2017.

More surprising, there was a significant inversion over time in the percentage of students embracing and those rejecting a role for God in the origin of humans. In 1986, the majority (60%) of our students believed God had something to do with the origin of humans. In 2017, this view was embraced by only a small minority (29%) of the class, a decrease of about 50% over the 32 year interval. The percentage of students convinced that God had nothing to do with the origin of humans increased from a small minority (25%) in 1986 to the clear majority view (62%) in 2017.

A broader shift

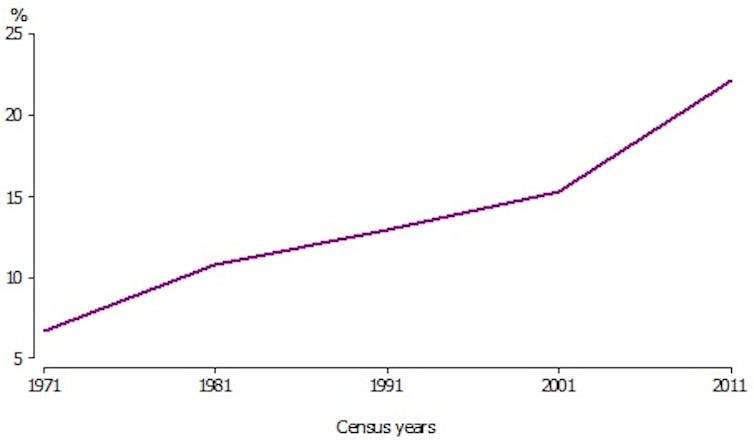

The Australian public census appears to reflect similar directions of change in the Australian public in general. The percentage of Australians who indicated they had “no religion” on the Census rose from 22.3% in 2011 to 30.1% in 2016.

Percentage of people reporting no religion, 1971 to 2011

From Australian Social Trends, November 2013.

ABS

From Australian Social Trends, November 2013.

ABS

In the same time period, the percentage of students selecting “God had no part in the evolution of humans” on our survey rose from 52.1% in 2011 to 62.4% in 2016. This suggests the results from our 32 year survey may reflect at least similar directions of change in the Australian public as a whole.

Australia has a less religious past than some

Reports of long-term trends in views about the origins of humans are rare and, in most cases, limited to surveys of adult populations in the US. More rare are surveys of these beliefs in other countries.

The extent and pace of decline in the Australian students’ commitment to religious views about divine creation contrast with the views held by the American public.

Significant differences between the balance of views in the US and Australia may in part reflect different cultural backgrounds. Most of the early Europeans who travelled to North America were deeply religious Protestants. In contrast, most Europeans who moved to Australia, some as “guests” of Her Majesty’s prison system, were far less concerned with religious matters and far more inclined to spend Sundays at the pub.

The first Christian cleric in Australia, Reverend Richard Johnson who sailed with the First Fleet, had an incredibly hard time trying to raise funds to build any form of church. He ended up paying for the building out of his own wages.

His church was finally built in 1794 but, shortly after completion, was deliberately burned down. After losing the church and much of his own income, Reverend Johnson filed for a leave of absence to visit England. He never returned.

Understanding the broader shift

A key factor cited by many which may be contributing to the long-term shift away from theistic views of human origins include increasing access to a massive amount of web-based and media-presented scientific understanding about the origin of the natural world. Before this was available, cultural, community and parental values may well have been the most influential factors in forming student opinions about supernatural versus natural origins.

But it may also be that people are finding it difficult to maintain faith in miraculous explanations for what are otherwise increasingly found to be natural phenomena. Exposure of claims for contemporary miracles, such as statues of Mary that appear to weep tears of blood, don’t help to stem growth in scepticism about miracles in general.

Read more: Australia needs more state fossil emblems, but let the public decide

We will continue to run this survey in UNSW Sydney for as long as practical. But it would be interesting to begin the same type of long-term survey program in the range of secondary schools that contribute most of the students to UNSW Sydney.

Similarly, it would be interesting to see long-term annual surveys of this kind conducted in other tertiary education institutions in Australia, and overseas. It’s always possible (although unlikely) that our students’ opinions are not broadly representative of Australian first-year university students as a whole. Having similar data from other institutions would give us a more nuanced view.

Finally, it would be interesting, if possible, to ask the same question of the same cohort of students in third-year to see if a university education results in a change in opinion among those who arrived with creationist views.

Professor Mike Archer was the lead author of a team of scientists who conducted and interpreted the results reported here. The others are (in order of authorship): Associate Professor Alistair G.B. Poore (UNSW Sydney); Ms Alexis M. Horn (Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation); Dr Hayley Bates (UNSW Sydney); Assoc. Prof. Stephen Bonser (UNSW Sydney); Matthew Hunt (Charles Sturt University); Jonathan Russell (UNSW Sydney); Nikkita P. Archer (37a Hannam St, Bardwell Valley); Dylan J. Bye (37a Hannam St, Bardwell Valley); Prof. E. James Kehoe (UNSW Sydney).

Authors: Mike Archer, Professor, Pangea Research Centre, UNSW