A recipe for mummy preservation existed 1,500 years before the Pharaohs

- Written by Jana Jones, Research Fellow in Ancient History, Macquarie University

Ancient Egypt continues to throw up one fabulous surprise after another.

Today my colleagues and I published our analysis of an intact Egyptian prehistoric body (from around 3700-3500 BC) that had been housed in a museum in Turin, Italy, since 1901. The results provide strong evidence that embalming was taking place 1,500 years earlier than previously accepted.

The dead man was previously assumed to have been naturally mummified by the desiccating action of the hot, dry desert sand. But now we know it was deliberately preserved.

Together with our previous research, this new information tells us that the prehistoric Egyptians – those living 1,500 or more years before the Pharaohs – already had knowledge of the processes required to preserve the body, and practised a developed religious belief system about the afterlife.

Read more: How Lincoln's embrace of embalming birthed the American funeral industry

The mummy was stored in a museum in Turin, Italy.

Journal of Egyptian Archeology

The mummy was stored in a museum in Turin, Italy.

Journal of Egyptian Archeology

We had hints

Prior to this new study, our analysis of funerary wrappings from prehistoric bodies from sites in central Egypt proved that the ancient Egyptians who lived before the time of the pharaohs used some body preservation techniques.

Reports of pellets of resin in pouches with the bodies in early burials excavated at prehistoric sites at Badari and Mostagedda in Middle Egypt (c. 4500-3350 BC) had made me wonder whether they were already using resin in a rudimentary form of mummification.

Resin is an substance harvested from certain trees, particularly pine, and is a preservative component of embalming mixtures.

Read more: Gummy mummies: Egyptians used a millennia-old embalming recipe

In our previous work we did not have whole bodies – only small fragments of linen in British museums. The pieces of fabric were the only surviving evidence the bodies had been wrapped, and had been donated by the excavators in the early 20th century in return for funding for excavation.

Working with an archeological chemist, my colleague Ron Oldfield and I identified resin in the wrappings.

But we didn’t have any further samples to expand this work – until now.

We don’t know what killed the man referred to as ‘the Turin mummy’.

R. Bianucci, Author provided

We don’t know what killed the man referred to as ‘the Turin mummy’.

R. Bianucci, Author provided

Preparing for the afterlife

The central tenet of ancient Egyptian mummification was preservation of a perfect body so that it could enter into the afterlife as a complete entity. If a crocodile had bitten off a leg, a wooden prosthesis would be substituted.

The wrapped bodies at prehistoric sites generally had not come under intense scrutiny when excavated, because in the 19th and early 20th centuries interest was overwhelmingly in the artefacts. Furthermore, there had been no reason to believe that the prehistoric Egyptians were using any preservative balms on their dead.

Like the British, the Italians were conducting their own excavations to fill the Museo Egizio in Turin. Perhaps the best-known archaeologist is Ernesto Schiaparelli, director of the museum between 1895 and 1928.

Schiaparelli went on a number of missions to Egypt to excavate and purchase mummies and artefacts from antiquities dealers, including the prehistoric body in this current study (identified as “Turin S. 293, RCGE 16550”), bought between 1900 and 1901.

It is only one of 20 bodies of this period (c. 3600 BC) in international museums. Although there are few written records on the body’s provenance, Gebelein in Middle Egypt is the most probable source.

A recipe for preservation

In 2014, a research grant from Macquarie University afforded a unique opportunity to forensically examine this Turin mummy.

Working with an international team, we took minute samples of textile and skin for biochemical analysis, radiocarbon dating, textile analysis and DNA analysis of pathogenic bacteria.

The mummy had not undergone conservation in the museum which meant that contamination was minimal, making him an ideal subject for scientific investigation. The downside of not having been conserved and consolidated is that he is extremely fragile and damaged.

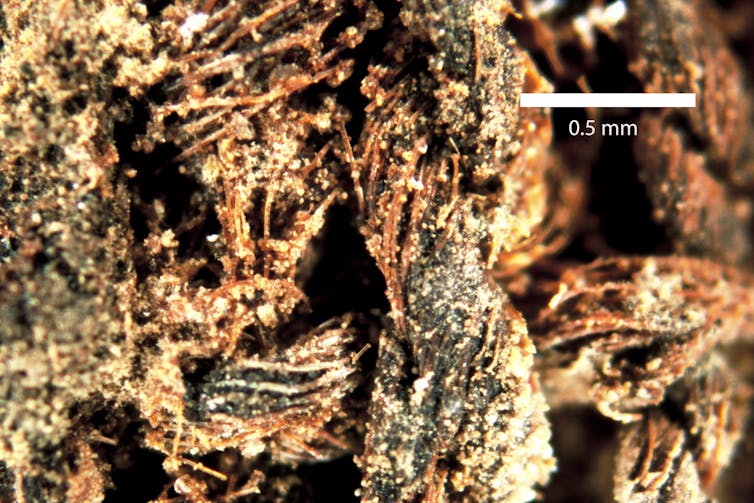

A close-up of linen fibres the Turin mummy was wrapped in for burial.

Ron Oldfield, Author provided

A close-up of linen fibres the Turin mummy was wrapped in for burial.

Ron Oldfield, Author provided

Chemical analysis of the residues on the textile wrappings from the torso and wrist using a technique known as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry revealed the presence of a plant oil or animal fat, a sugar/gum, a conifer resin and an aromatic plant extract.

The resin and aromatic plant extracts are the two main antibacterial components that would have repelled insects and preserved the soft tissue underneath. Chemical signatures indicate gentle heating, so it was indeed a “recipe” that was probably applied by dipping the linen into the melted mixture and then wrapping.

Egyptian ingenuity

Radiocarbon dating of linen – one sample each from the body and the basket of fragments accompanying the body – gave a date range of around 3700-3500 BC. Both samples shared the same early spinning technology observed in Egyptian linen between about 5000 BC and 3600 BC, when a momentous change in the direction of the spin took place.

Close up of basket fibres found with the Turin mummy, indicating a ‘prehistoric’ spin direction.

Ron Oldfield, Author provided

Close up of basket fibres found with the Turin mummy, indicating a ‘prehistoric’ spin direction.

Ron Oldfield, Author provided

No pathogenic DNA was detected by metagenomics, either because it had not survived the environmental conditions in Egypt or the museum (which until recently was not climate-controlled).

As a result, we do not know whether he died from an infectious disease. Furthermore, his extremely fragile state prevented him from being moved for X-ray analysis.

Together with our previous research, the information gleaned from this complete mummy tells us that the prehistoric Egyptians already had knowledge of the processes required to preserve the body, as well as an already developed religious belief system about the afterlife.

They had access to resins from the Eastern Mediterranean, suggesting long-distance trade. That similar components were used in the balms in burials 200 km apart, and indeed continued to be used in similar proportions by the pharaonic period embalmers when their skills were at their peak some 2,500 years later, shows the enduring nature of ancient Egyptian ingenuity.

Authors: Jana Jones, Research Fellow in Ancient History, Macquarie University