Seven beautiful images that share new stories of science

- Written by Jason Bainbridge, Professor of Media and Communication, Head of the School of Creative Industries, University of South Australia

No one would doubt the importance of images in our contemporary culture. We live every day surrounded by them, saturated by them, trading in them.

As a way to tap into the power of the image, the University of South Australia runs an annual research photography competition that is open for submissions from all students and staff.

Of 18 photos that made the finalist round, the winner of the 2018 Images of Research competition is “Clotted” by Eli Moore. It reveals the microscopic details of a blood clot caused by a medical device designed to treat cardiovascular disease (shown at top).

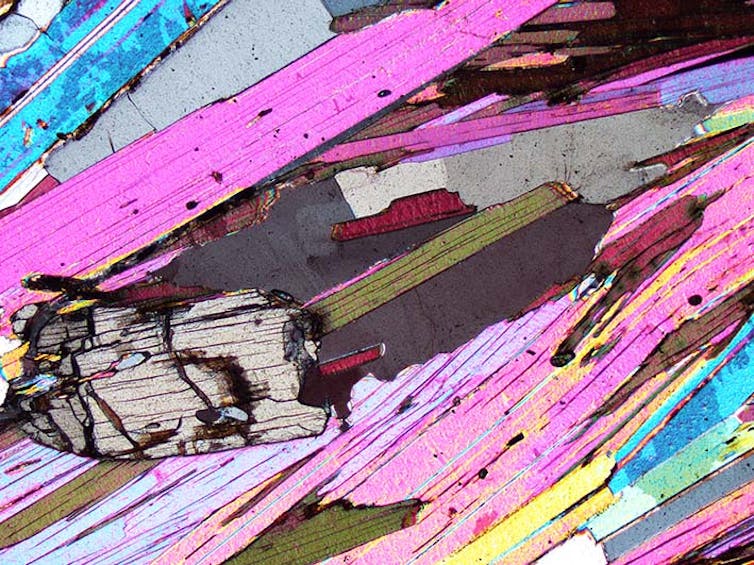

‘A journey into Australia’s tumultuous geological past, and into a groovy future’ – an image by Jan Varga that was awarded second prize in UniSA’s 2018 Images of Research competition.

UniSA, Author provided

‘A journey into Australia’s tumultuous geological past, and into a groovy future’ – an image by Jan Varga that was awarded second prize in UniSA’s 2018 Images of Research competition.

UniSA, Author provided

The runner up, shown above, was submitted by Jan Varga. Jan said:

See that cracked, brown, slightly oblique and high-relief grain near the bottom left? That is the mineral kyanite, and it tells an important story related to the conditions at which this rock formed through time.

In fact, this rock has been dated to 1.78 billion years old, and experienced high temperatures and pressures around 380 million years ago forming the Alice Springs mountain belt.

Each image of the 18 finalists provides a window on applied research related to social issues, health concerns, wicked problems and ordinary people. Importantly, they are removed from the stereotype of the isolated researcher working alone in an ivory tower.

Corinna Di Niro’s ‘The Virtual Actor’ image poses the question whether there is more to being an audience member than just sitting in the dark.

UniSA, Author provided

Corinna Di Niro’s ‘The Virtual Actor’ image poses the question whether there is more to being an audience member than just sitting in the dark.

UniSA, Author provided

Read more: Neuroscience in pictures: the best images of the year

A blissful clarity

We understand the importance of images in communication through a field known as semiotics, which began around 60 years ago.

In the late 1950s, French theorist Roland Barthes wrote of images’ ability to distil complex ideas and details into “a blissful clarity” creating “a world wide open and wallowing in the evident” where “things appear to mean something by themselves”.

Barthes followed Ferdinand de Saussure and Claude Lévi-Strauss in the field of semiotics, studying the social condition through the interrelated concepts of the sign, the signifier and the signified. These terms provide a toolkit for understanding how images function.

UniSA researcher Ashleigh Smith’s photograph ‘Intergenerational instruction’ comes from her work exploring the benefits of children and people with dementia spending time together.

UniSA, Author provided

UniSA researcher Ashleigh Smith’s photograph ‘Intergenerational instruction’ comes from her work exploring the benefits of children and people with dementia spending time together.

UniSA, Author provided

For semiologists, signs are units of meaning composed of two elements: a physical element (the image that you can see, called the signifier) and a mental element represented by that image (what the image makes you think about or feel, called the signified).

These two elements are a part of every sign, every image. You can never have a signifier without a signified, or a signified without a signifier. The process where they work together to produce meaning is called signification.

Nadeem Nazaar’s image ‘Umbilical cord’ is a representation of feticide.

UniSA, Author provided

Nadeem Nazaar’s image ‘Umbilical cord’ is a representation of feticide.

UniSA, Author provided

Read more: Museum or not? The changing face of curated science, tech, art and culture

Ideologies in disguise

Barthes’ primary interest in images was around exploring the political subtexts of consumerism and nationalism in the 1950s, particularly where they intersected in magazine covers and photography.

Barthes argued that they produced ideologies that were so widely accepted, so familiar, that they were no longer recognised as ideologies. He referred to such ideologies as myths – what we might call the “isms” like consumerism and nationalism or imperialism and capitalism. Those systems that simultaneously provide us with ways of understanding the world while also being imposed upon us.

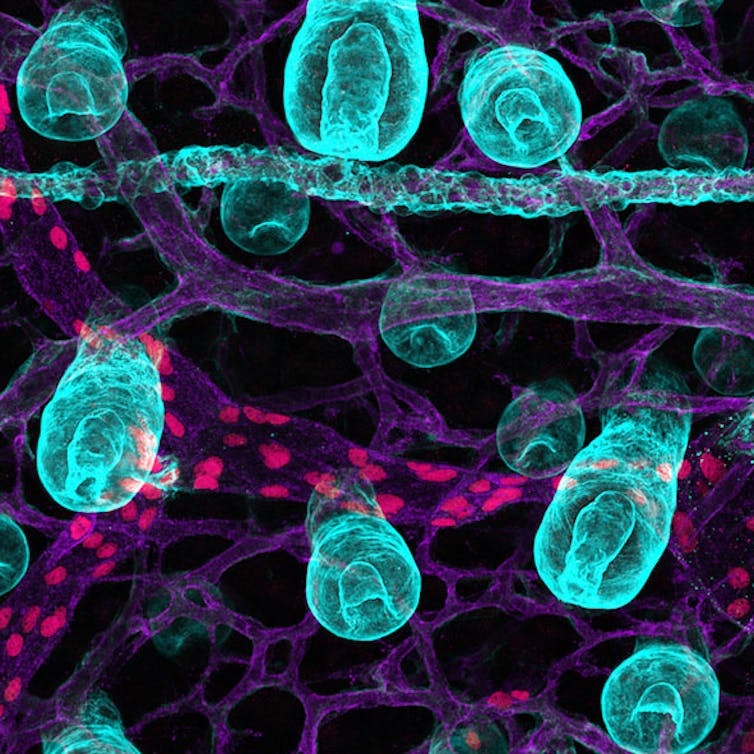

‘Hairy worms’ by Genevieve Secker highlights features in the skin of a developing mouse embryo.

UniSA, Author provided

‘Hairy worms’ by Genevieve Secker highlights features in the skin of a developing mouse embryo.

UniSA, Author provided

Since Barthes, each advance in technology has added to the visual vocabulary of images available to us.

For example, a digital language based around images rather than words has evolved into texting conventions such as :-) and emojis. These are very basic signifiers and signifieds we all employ as mobile phone users today.

Read more: Why I use emoji in research and teaching

Images as a currency

Signification is the space where advertisers and public relations professionals work, encouraging you to think “McDonalds” rather than “hamburger” or “Google” rather than “search”.

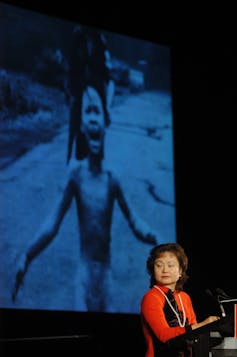

Kim Phuc in 2004 standing before an image of herself fleeing her village during the Vietnam War.

AAP Image/POOL

Kim Phuc in 2004 standing before an image of herself fleeing her village during the Vietnam War.

AAP Image/POOL

It is also the currency of social media: from the ephemeral images of Snapchat capturing a moment (or body part), to carefully constructed selfies and memes designed to go viral, to the strategic use of filters and framing to develop the fun and/or sexy images that populate Instagram, Tinder and Grindr.

Moving from entertainment to news media, signification is just as vital a part of journalism. Nick Ut’s 1972 photo of Kim Phuc – naked, burned by Agent Orange, running down a road – is one of the most common images we think of when we think about the Vietnam War.

Indeed, public sentiment around armed engagement in Vietnam changed because of the nature and power of the images the news media provided, leading to that conflict being described as the war that was lost in the living rooms of America.

What links all of these uses of images is Barthes’ underlying idea of the image being able to convey complex ideas, details and emotions quickly and succinctly.

Aeroplane safety guides are designed to be simple and clear.

from www.shutterstock.com

Aeroplane safety guides are designed to be simple and clear.

from www.shutterstock.com

Barthes’ blissful clarity has great utility for government, technology, legal and health organisations – where complicated and unfamiliar jargon can often lead to misunderstandings.

Think for example of the attempt at clarity provided by the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Security’s use of comics to dissuade asylum seekers from paying people smugglers to travel to Australia or, more successfully, the clarity provided by the safety guide in the seat pocket of an aeroplane.

Read more: Refugee crisis: the immediate and lasting impacts of powerful images

Better use of images is incredibly important for academic researchers, where fields of knowledge each have their own distinct and complex vocabularies that can inhibit or delay the translation of research findings to broader audiences.

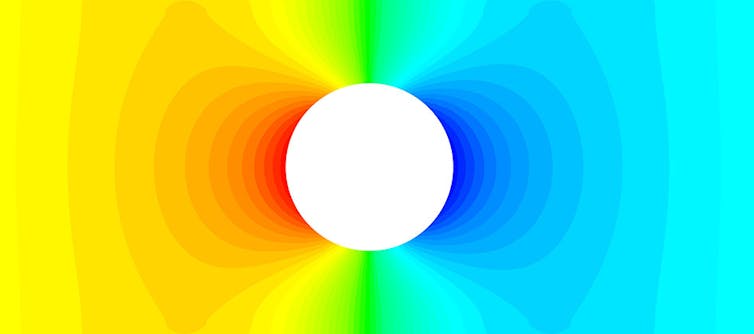

Moein Kashani’s image ‘A Butterfly in Microchannel’ reveals how liquids flow in tiny channels.

UniSA, Author provided

Moein Kashani’s image ‘A Butterfly in Microchannel’ reveals how liquids flow in tiny channels.

UniSA, Author provided

Here, images can provide a common language that engages the general public with something they know, something that is already familiar to them, while providing a new perspective on, or contribution to, knowledge in that area.

In this way, the image becomes an important way to close the gap between academy and community, putting researchers in direct contact with the general public.

Authors: Jason Bainbridge, Professor of Media and Communication, Head of the School of Creative Industries, University of South Australia

Read more http://theconversation.com/seven-beautiful-images-that-share-new-stories-of-science-99677