five medicinal plants used by Aboriginal Australians

- Written by Beth Gott, Honorary Research Fellow, Monash University

People have lived in Australia for at least 65,000 years. In all those generations the land provided original Australians with everything they needed for a healthy life.

At least half the food eaten by the first Australians came from plants, and it was the task of women to collect them. Fruits, seeds and greens were seasonal, but roots could usually be dug up all year round, because the earth acted as a natural storage cupboard.

The particular plants eaten or used as medicine varied in different parts of Australia. In Arnhem Land, North Queensland and the Kimberley, many tropical trees bear fruits and seeds, such as native figs (Ficus spp.), lilly-pillies (Acmena, Eugenia and Syzygium spp.) and macadamia nuts.

In Central Australia, where water is scarce, plants are spread thinly over the land. Here the people relied more on the seeds of native grasses and wattles such as mulga (Acacia aneura), wiry wattle (Acacia coriacea) and even the coolabah tree (Eucalyptus microtheca).

In the southern parts of Australia, roots (applying that word to all the underground parts of a plant) were the most important foods.

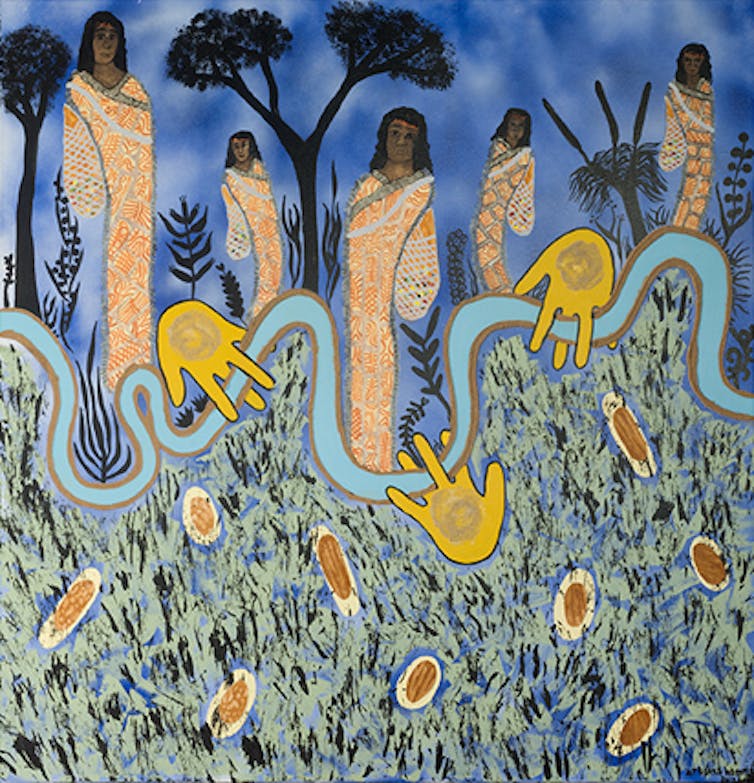

Treahna Hamm (b. 1965), Dhungala cool burn, 2017 (detail, one panel), acrylic paint, river sand, bark ink, paper 100.9×114cm (each of three panels). MHM2017.2, © Treahna Hamm.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

Treahna Hamm (b. 1965), Dhungala cool burn, 2017 (detail, one panel), acrylic paint, river sand, bark ink, paper 100.9×114cm (each of three panels). MHM2017.2, © Treahna Hamm.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

In terms of medicines, many different parts of plants were used. Native mints (Mentha spp.) were remedies for coughs and colds, while the gum from gum trees, which is rich in tannin, was used for burns. The green plum (Buchanania obovata) is enormously rich in vitamin C.

Here are five other plants that have medicinal uses:

1. Kangaroo apple (Solanum aviculare or Solanum laciniatum)

This is a great example of a food source and medicinal plant for many Victorian Aboriginal clan groups. This shrub varies in height. Its leaves resemble a kangaroo’s paw and it produces purple flowers.

The early fruits that form are at first yellow or green and highly poisonous, but can be eaten when they are at their ripest, turning a blood-orange colour. The fruit contains high levels of the alkaloid solanine, which can be infused from the leaves with hot water to create steroids.

Also known as bush apple, it has been farmed in several parts of the world to produce and manufacture oral contraceptives, using extracts from the young leaves and green fruits.

Kathrine ‘Kat’ Clarke (b.1988) , Dyirr-i-laiurrk, kangaroo apple (Solanum aviculare), 2018, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 20.3×14.5cm. MHM2018.23 © Kathrine Clarke.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

Kathrine ‘Kat’ Clarke (b.1988) , Dyirr-i-laiurrk, kangaroo apple (Solanum aviculare), 2018, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 20.3×14.5cm. MHM2018.23 © Kathrine Clarke.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

2. Wattles (Acacia spp.)

Australia has more than 1,000 wattle species. The gum of some species (golden, silver and black wattles) was an important food as well as a useful cement. The seeds of other species are high in protein and carbohydrate and in arid areas were eaten both green and dry.

Wattle blossom was hung in people’s huts to promote sleep. In Victoria, the bark of blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon) was infused and used to bathe rheumatic joints, or ingested as a mild sedative for rheumatism or indigestion.

Treahna Hamm (b. 1965), Yorta Yorta bush medicine first aid kit, 2017 Paperbark, kurrajong pods, Lomandra, she-oak pods, bark ink, riverbed clay, charcoal, billabong sediment, raffia, bottlebrush wood and bloom, ash, possum bone, mussel shell, black wattle bark, stringybark, river sand, Eucalyptus leaves, tree bark, sap, 4×12×27cm, MHM2017.1, © Treahna Hamm.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

Treahna Hamm (b. 1965), Yorta Yorta bush medicine first aid kit, 2017 Paperbark, kurrajong pods, Lomandra, she-oak pods, bark ink, riverbed clay, charcoal, billabong sediment, raffia, bottlebrush wood and bloom, ash, possum bone, mussel shell, black wattle bark, stringybark, river sand, Eucalyptus leaves, tree bark, sap, 4×12×27cm, MHM2017.1, © Treahna Hamm.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

3. Old man’s weed (Centipeda cunninghamii)

Commonly found along the Murray River, as well as in other low-lying, swampy habitats, this plant is useful for treating many complaints, including eye infections, tuberculosis and skin complaints. It is administered as an extract in water, or sometimes rubbed onto the skin.

It’s usually used for colds and coughs and chest infections, but, being a natural restorative plant, it can help strengthen the immune system and mobility.

Kathrine ‘Kat’ Clarke (b.1988), Gukwonderuk (Wotjobaluk) or old man’s weed (Centipeda cunninghamii), 2018, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 20.4×14.7cm, MHM2018.22, © Kathrine Clarke.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

Kathrine ‘Kat’ Clarke (b.1988), Gukwonderuk (Wotjobaluk) or old man’s weed (Centipeda cunninghamii), 2018, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 20.4×14.7cm, MHM2018.22, © Kathrine Clarke.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

4. Drooping she-oak (Allocasuarina verticillata)

In Victoria, mature cones from this tree were ground up and applied to sores to treat rheumatism. Extracts from the bark and wood can also be used as a general medicine.

Read more: Traditional Aboriginal healers should work alongside doctors to help close the gap

5. Hop bush (Dodonaea viscosa)

This plant grows across Australia. In Queensland the juice of the root was applied for toothache and cuts.

The chewed leaf and juice were put on stonefish and stingray stings and bound up for four or five days.

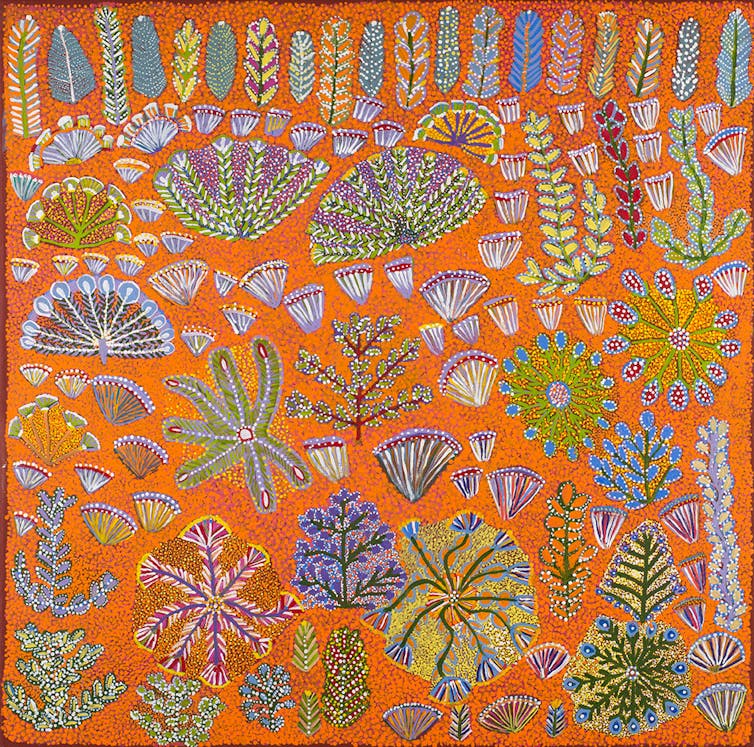

Rosie Ngwarraye Ross (b. 1951), Bush flowers and bush medicine plants, 2015 acrylic on linen, 91×91cm, MHM2017.3, © Artists of Ampilatwatja.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

Rosie Ngwarraye Ross (b. 1951), Bush flowers and bush medicine plants, 2015 acrylic on linen, 91×91cm, MHM2017.3, © Artists of Ampilatwatja.

Medical History Museum, Author provided

Kathrine “Kat” Clarke, artist and proud woman from the Wimmera, contributed to this article.

The artworks used in this article are on display at the University of Melbourne’s Medical History Museum, as part of The art of healing: Australian Indigenous bush medicine exhibition, which runs until September 28. This article is made up of essay extracts published in the exhibition’s catalogue.

Authors: Beth Gott, Honorary Research Fellow, Monash University