Darwin's On the Origin of Species

- Written by Julia Kindt, Associate Professor, Department of Classics and Ancient History, University of Sydney

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (originally published in 1859) shares a deplorable fate with many other classics: it is known to everyone, yet rarely read.

This is a shame, not only because there is much more to Darwin’s theory than the familiar principles of mutation, variation, natural selection, and evolution that have entered popular knowledge as Darwinian buzzwords. The book also gives unique insight into the intellectual milieu in which he developed his theory and his struggles to convince his peers of its veracity.

Indeed in this age of the counter-factual and pseudo-factual, acquaintance with the foundations of our scientific tradition — and insights into the struggles of their creation — seems a matter of some urgency.

Charles Darwin aged 51.

Wikimedia Commons

Charles Darwin aged 51.

Wikimedia Commons

In the introduction alone, we learn that Darwin first conceived of his theory when travelling the world as a naturalist on board HMS Beagle (1831-6), that he had kept collecting data in support of it ever since, that he even wrote a rough draft (he calls it “a sketch of the conclusions”) many years earlier, and that he was prompted to publish it (20 years later) only because his contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace had recently sent him a “memoir” reaching a similar conclusion.

The core of the theory, as laid out in the first few chapters of the book, is quickly explained. Plants and animals produce more individuals than nature can sustain in each generation. These individuals vary in looks and in physical and behavioural characteristics, and they are able to pass on this variation to the next generation. Those individuals better suited to their environment have an advantage and are in turn more likely to survive to give their features to future generations.

Yet the bare bones of his theory of evolution are only part of what shapes this book. Darwin also communicates the obstacles he had to overcome to ensure its success and to turn it into what it became: a foundational text of the biological sciences that influenced all sorts of other disciplines, including anthropology, religious studies, and the Classics.

Creationism and evolution

At the time Darwin wrote, the prevailing form of explanation of the origins of life was creationism, which held that a divine Creator had generated life in all its variety. To creationists, the theory of evolution offered a rival way of explaining the origin of species – through descent from common ancestors, not a divine agent.

Charles Darwin’s 1837 sketch, his first diagram of an evolutionary tree from his First Notebook on Transmutation of Species.

Wikimedia Commons

Charles Darwin’s 1837 sketch, his first diagram of an evolutionary tree from his First Notebook on Transmutation of Species.

Wikimedia Commons

Darwin was well aware that his theory might prove difficult to accept for those believing in a Creator. His obsession with the factual was one way of addressing this problem, direct rebuttals of creationism were another. Throughout the book, he repeatedly addresses creationist views and shows that they are incompatible with the evidence.

Darwin himself was not against the idea of a divine creator. Rather, he sought to situate the scientific reading of the world within a religious worldview. In the book’s conclusion he states: “I should infer from analogy that probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed by the Creator.”

This is to say that, while life was first created by a God, it later became subject to the laws of mutation, variation, and natural selection – the evolutionary forces described by Darwin.

This really was a congenial move, offering a compromise between religious and scientific explanations of life. As long as divine creation occurred prior to and outside of nature and its laws of cause and effect, both explanations could, at least in principle, stand side by side. And to some extent it worked. Some of Darwin’s contemporaries found that life’s subsequent capacity to evolve brought out the real spark of the original act of creation. Others, however, did not buy it. To them, Darwin’s theory constituted a frontal attack on religion, the idea of a divine creator, and the tenet that God had created man in his own image.

An ominous absence

In this context, it is noticeable that in On the Origin of Species Darwin stays well clear of the problematic issue of human descent. If there is a striking omission in the book, it is man. Darwin originally intended to include a chapter on human evolution but later decided against it. As a result, the descent of Homo sapiens does not really feature in this elaborate discussion of the forces that drive the evolution of species.

Editorial cartoon depicting Charles Darwin as an ape, 1871.

Wikimedia Commons

Editorial cartoon depicting Charles Darwin as an ape, 1871.

Wikimedia Commons

Darwin obviously considered the book controversial enough without agitating his readers unnecessarily by touching on human evolution. And his instincts did not betray him: Right from the day of its publication, the book became something of a bestseller. Also right from the start, it elicited mixed responses. Some saw it for the foundational work of the biological sciences it eventually became. Others decried it as a serious threat to the core of humanity.

Darwin eventually came to address human evolution in a separate volume, entitled The Descent of Man. Published in 1871, 12 years after On the Origin of Species, this book offered a detailed discussion of man’s descent from ape-like ancestors as well as the link between sexual selection and human race. Invariably, perhaps, its publication caused a fresh wave of outrage, criticism, and debate. By then, however, Darwin’s theory had already become accepted in certain parts of academe and beyond.

The power of the factual

Mistletoe on a tree in England.

Scrappy Annie/flickr, CC BY

Mistletoe on a tree in England.

Scrappy Annie/flickr, CC BY

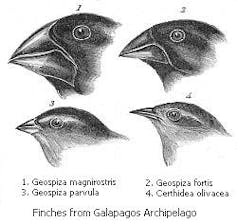

Throughout his writing, Darwin sought to counter potential adverse responses to his theory with an onslaught of fact. On the Origin of Species is peppered with examples from the natural world illustrating the principles of evolutionary theory in practice.

The struggle for existence, for example, becomes tangible in several seedlings of the mistletoe competing for resources on the same branch of a tree; variation and natural selection has resulted in insects with the astonishing ability to mimic features in their natural environment such as leaves or branches. Correlations between physical characteristics of animals emerge in a whole plethora of minute observations such as these:

Hairless dogs have imperfect teeth; long-haired and coarse haired animals are apt to have … long or many horns; pigeons with feathered feet have skin between their outer toes; pigeons with short beaks have small feet, and those with long beak large feet.

Darwin was well-versed in the zoological and botanical literature of the day. He cites other scholars’ works in support of his theory whenever possible (and yet curiously, repeatedly apologises for not citing enough evidence). The result is a rich exposition of life in all its manifestations, which sometimes veers into the finicky – a problem made worse by Darwin’s notoriously long sentences – but never loses sight of its central argument.

Darwin s finches.

Wikimedia Commons

Darwin s finches.

Wikimedia Commons

Darwin’s sustained concerns with presenting a convincing case reveal the kind of reception he anticipated his book would have. He was well aware that it had the potential to redefine the foundations of biology. He explicitly says so in the conclusion: “When the views advanced by me in this volume … are generally admitted, we can dimly foresee that there will be a considerable revolution in natural history.”

And Darwin’s views certainly did revolutionize. Yet before they could do so, they had to be accepted as fact. To ensure this he evoked the power of the factual itself.

Ultimately Darwin was successful. Even though these days creationism is witnessing a revival in some circles, no serious student of biology would doubt that the origin of species (including the human species) is grounded in exactly those evolutionary forces Darwin described.

Evolutionism within and beyond Darwin

As is frequently the case with the most powerful ideas, Darwin’s theory of evolution caught on in other areas of thought, too. In particular, during the latter part of the 19th century, all sorts of theories emerged seeking to apply the concept of evolution elsewhere. It became fashionable to speak of the “evolution” of human societies, for example, or of human cultures, religions – even of the cosmos.

Charles Darwin’s working room in Down House, where he wrote On the Origin of Species, Kent, United Kingdom.

shutterstock

Charles Darwin’s working room in Down House, where he wrote On the Origin of Species, Kent, United Kingdom.

shutterstock

A common explanatory pattern used in this context was the idea that phenomena such as culture or religion evolved from simple (“primitive”) forms to more complex ones. And, as one might guess, “more complex’ often equated simply with the present, Western culture and society, and the religion that shaped it: Christianity. The ideological point of this mode of explanation is easily discerned: Evolutionism here fed into ideas of European superiority, domination, and colonialism.

A particular nasty interpretation of Darwin’s theory came to be known as "social Darwinism”. It transferred the ideas of a “struggle for existence” and the “survival of the fittest” to human society, where they were used as an argument against social benefits for the poor and disadvantaged. In the most serious consequence, this lead to racism, eugenics, forced sterilisations, and the euthanasia of “unfit” people.

Yet this was a blatant misuse of Darwin’s theory, which was never meant as a prescription about how to manage a society. Moreover, ideas about racial superiority lacked any scientific basis and were not shared by Darwin. Quite the contrary: his insights into the common biological foundations of all humanity made Darwin a strong supporter of abolitionism (the doctrine advocating for the abolition of slavery). People simply twisted Darwin’s ideas to promote their own notions of superiority and the ideological agendas based on them.

Darwin today

Social Darwinism ultimately came to an end because it was unsupported by science. At the same time, ideas about cultural evolution fell out of fashion, as did ideas about allegedly “primitive” societies. These days, cultures of the past and present are no longer set against each other but appreciated in their own right, without seeking to establish a hierarchy between them.

Yet evolutionary theory is still going strong in disciplines such as computer science, medicine, and agriculture. In computer science, “genetic algorithms” solve optimisation problems by mimicking the process of natural selection. In medicine, the looming catastrophe of widespread antibiotic resistance is fundamentally an evolutionary problem: by overusing antibiotics, we have inadvertently favoured those rare bacteria that can withstand our drugs.

goodreads

To prevent a decidedly bleak future where antibiotics are useless, researchers are increasingly using evolutionary theory to develop new ways of preventing resistance. Cancer, obesity and autoimmune conditions such as allergies and asthma can be understood (and possibly treated) through the lens of evolutionary science.

About 170 years after its first publication, On the Origin of Species and the theory it has come to represent still define the way in which the biological sciences conceive the dazzling diversity of life. Its continuing legacy consists in laying out a view of life as “one grand system” and in having described the biological mechanisms shaping it.

Yet the book also shows that the ultimate prevalence of the theory of evolution over rival forms of explanation did not come easily. Darwin had to think carefully how to convince his contemporaries of its validity. He had to defend himself against accusations of blasphemy; some of the resulting ridicule targeted him personally.

The traces of this struggle are clearly visible in his work. This alone makes it a must-read for all budding scientists, both real and armchair.

goodreads

To prevent a decidedly bleak future where antibiotics are useless, researchers are increasingly using evolutionary theory to develop new ways of preventing resistance. Cancer, obesity and autoimmune conditions such as allergies and asthma can be understood (and possibly treated) through the lens of evolutionary science.

About 170 years after its first publication, On the Origin of Species and the theory it has come to represent still define the way in which the biological sciences conceive the dazzling diversity of life. Its continuing legacy consists in laying out a view of life as “one grand system” and in having described the biological mechanisms shaping it.

Yet the book also shows that the ultimate prevalence of the theory of evolution over rival forms of explanation did not come easily. Darwin had to think carefully how to convince his contemporaries of its validity. He had to defend himself against accusations of blasphemy; some of the resulting ridicule targeted him personally.

The traces of this struggle are clearly visible in his work. This alone makes it a must-read for all budding scientists, both real and armchair.

Authors: Julia Kindt, Associate Professor, Department of Classics and Ancient History, University of Sydney

Read more http://theconversation.com/guide-to-the-classics-darwins-on-the-origin-of-species-96533