Indigenous communities are reworking urban planning, but planners need to accept their history

- Written by Libby Porter, Vice-Chancellor's Principal Research Fellow, RMIT University

This is the sixth article in our series, Cities for Everyone, which explores how members of different communities experience and shape our cities, and how we can create better public spaces for everyone.

Nearly 80% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia live in urban areas but cities often exclude and marginalise them.

Urban planning and policy have been central to this, and the harms can be seen in key moments and processes that have shaped Australia’s urban environments.

Today, Indigenous people continue to be seen as “out of place” in the city. Their rights and interests remain largely invisible in urban history, policy and planning practice.

Read more: How can we meaningfully recognise cities as Indigenous places?

To rectify the unequal place of Indigenous peoples in our cities and work towards urban land justice, we need to consider the planning processes that have contributed to the marginalisation of Indigenous people over the course of Australian history.

The draining of the West Melbourne Swamp, a significant wetland for Aboriginal people, began in the 1870s under the supervision of the Public Works Department.

Henry L Cox (Henry Laird)/SLV

The draining of the West Melbourne Swamp, a significant wetland for Aboriginal people, began in the 1870s under the supervision of the Public Works Department.

Henry L Cox (Henry Laird)/SLV

Planning segregation and assimilation

Planning has long imagined that social problems can be resolved through spatial organisation and design. It is an activity that occurred even before the profession of “planning” emerged in the 20th century.

The earliest activities of Australian settlement dismissed Indigenous systems of law and governance. Colonial agents such as surveyors, cartographers, Aboriginal protectors and governors sought to remove people from growing towns. They used maps, zones and boundaries to control Indigenous peoples’ movement and to symbolically erase their connections with landscapes.

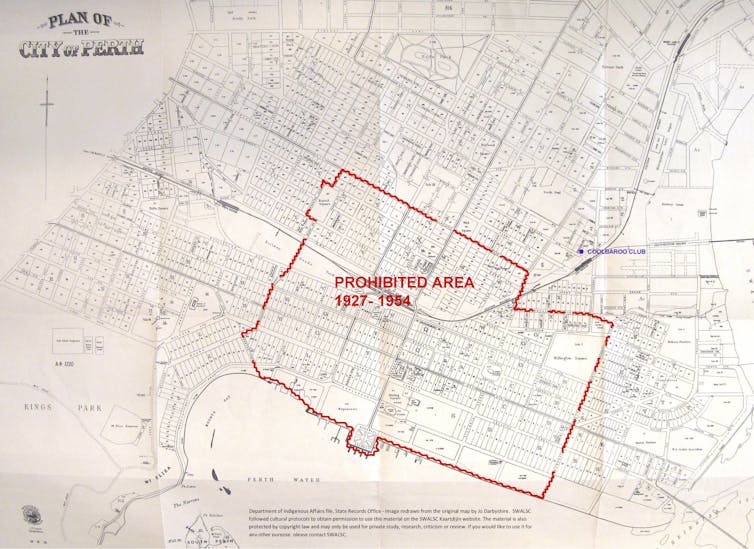

Between 1927 and 1954, Aboriginal people were prohibited from entering the centre of Perth.

South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, Author provided (No reuse)

Between 1927 and 1954, Aboriginal people were prohibited from entering the centre of Perth.

South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, Author provided (No reuse)

Populations were segregated on the basis of race as small Aboriginal reserves were established, supposedly to “protect and civilise” Indigenous people. As expanding cities consumed more land and became denser, white anxiety about the threat of disease grew.

But these concerns did not consider the living conditions of the Indigenous nations. Aboriginal people were considered a “threat” to public health. In the minds of officials, this called for their containment and surveillance in reserves, which were pushed further away from urban areas, becoming smaller and more neglected.

Town boundaries were drawn and curfews set to regulate when and where Indigenous people used urban space. These were widely adopted practices. In places like Brisbane, Darwin, Perth and Broome, boundaries were used to control the movement, as well as economic and social opportunities, of Aboriginal people for decades. These practices extended well into the 20th century.

Coranderrk was one of six reserves in Victoria made to contain, regulate, civilise, convert to Christianity and oversee Aboriginal people.

State Library of Victoria

Coranderrk was one of six reserves in Victoria made to contain, regulate, civilise, convert to Christianity and oversee Aboriginal people.

State Library of Victoria

As Australian Indigenous policy shifted away from segregation towards assimilation, planning reflected and enacted this change. Reserves close to towns were closed and sold off. Coranderrk Reserve near Melbourne was closed in 1924. In the 1950s, the Kahlin Compound in Darwin was closed and its population moved to the more distant Bagot Reserve.

Aboriginal people were compelled to move out of these now-isolated reserves and back into urban areas. Inner-city suburbs, such as Redfern in Sydney and Fitzroy in Melbourne, became important places for sustaining social and political communities.

These inner-urban sites and communities were swept up in the wider urban renewal agenda that redeveloped cities through rezoning and the provision of new public housing. This was seen as way to resolve poverty.

Yet as the 1997 Bringing Them Home report noted:

The provision of public housing for Indigenous families brought them into conflict with government authorities and thereby at increased risk of having their children taken. For example, strict limits on visitors staying in public housing and restrictions on the number of family members that could live together took no account of Indigenous family and community relationships.

Aboriginal communities maintained a strong presence in Fitzroy and Collingwood until the 1950s, when the Housing Commission demolished large ‘slum’ areas and relocated their occupants.

Nick Carson/Wikipedia, CC BY

Aboriginal communities maintained a strong presence in Fitzroy and Collingwood until the 1950s, when the Housing Commission demolished large ‘slum’ areas and relocated their occupants.

Nick Carson/Wikipedia, CC BY

Urban policy and planning continue to perpetuate the perception that Indigenous people have no authentic place in urban areas.

However, none of these discriminatory policies and practices has ever gone unchallenged by Indigenous people. While it remains very difficult for Aboriginal peoples whose traditional country is now urbanised to achieve land justice, innovative solutions are being found in the face of these challenges.

Towards urban land justice

Indigenous-led initiatives under way today show how communities are reworking planning to achieve their aspirations. The land use agreements negotiated by the Yawuru native title holders of the Broome area provide a framework for reclaiming and using planning to realise local visions for commercial and residential development. Indigenous Architecture Design Victoria is leading new ways of planning and designing built environments.

A young boy walks past a sign at the Redfern Aboriginal tent embassy in Sydney in 2015.

AAP Image/Paul Miller

A young boy walks past a sign at the Redfern Aboriginal tent embassy in Sydney in 2015.

AAP Image/Paul Miller

Within the planning profession, this critical issue is starting to gain more attention. The Queensland government has passed legislation that acknowledges that planning should value, protect and promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges, values and traditions.

The Planning Institute of Australia adopted an education policy in 2016 that calls for all accredited tertiary planning degrees to address the relationship between Indigenous peoples and planning. This requires teachers and students to engage more deeply with the histories, theories and ethics of the profession. These are welcome early steps.

In the long term, advancing a genuine and just relationship between planning and Indigenous peoples means sharing the right to shape the course of urban development and to define what the problems are and what values matter. Planning thinking, methods, approaches and practice must continue to shift to support that aspiration.

Libby Porter, Sue Jackson and Louise Johnson are authors of a recent book, Planning in Indigenous Australia: From imperial foundations to postcolonial futures.

You can find the other articles in the series here.

Authors: Libby Porter, Vice-Chancellor's Principal Research Fellow, RMIT University