$500 million for the Great Barrier Reef is welcome, but we need a sea change in tactics too

- Written by Jon Brodie, Professorial Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University

The federal government’s announcement of more than A$500 million in funding for the Great Barrier Reef is good news. It appears to show a significant commitment to the reef’s preservation – something that has been lacking in recent years.

The new A$444 million package, which comes in the wake of the A$60 million previously announced in January, includes:

A$201 million to improve water quality by cutting fertiliser use and adopting new technologies and practices

A$100 million for research on coral resilience and adaptation

A$58 million to continue fighting crown-of-thorns starfish

A$45 million for community engagement, particularly among Traditional Owners

A$40 million to enhance monitoring and management on the GBR.

A spokesperson for federal environment minister Josh Frydenberg said the funding would be available immediately to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and that there was no predetermined time frame for the spending.

But one concern with the package is that it seems to give greatest weight to the strategies that are already being tried – and which have so far fallen a long way short of success.

Water quality

The government has not yet announced the timelines for rollout of the program. But if we assume that the A$201 million is funding for the next two years, this matches the current rate of water quality management funding - A$100 million a year, which has been in place since 2008.

Yet it is already clear that this existing funding is not reducing pollution loads on the GBR by the required extent. The federal and Queensland governments’ own annual report cards for 2015 and 2016 reveal limited success in improving water quality. It is also known from joint Australian and Queensland government analyses that the required funding to meet water quality targets is of the order of A$1 billion per year over the next 10 years.

In the region’s main industries, such as sugarcane cultivation and beef grazing, most land is still managed using methods that are well below best practice for water quality, such as fertiliser rates of application in sugarcane cultivation. According to the 2017 Scientific Consensus Statement on the GBR’s water quality, very limited progress has been made so far.

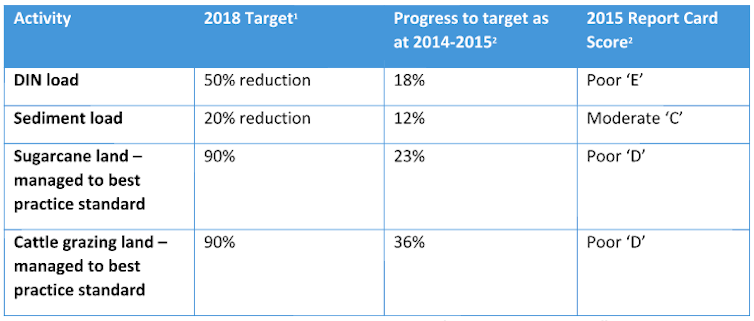

Progress towards targets and assigned scores in the 2015 Great Barrier Reef Report Card.

2017 Scientific Consensus Statement, Author provided

Progress towards targets and assigned scores in the 2015 Great Barrier Reef Report Card.

2017 Scientific Consensus Statement, Author provided

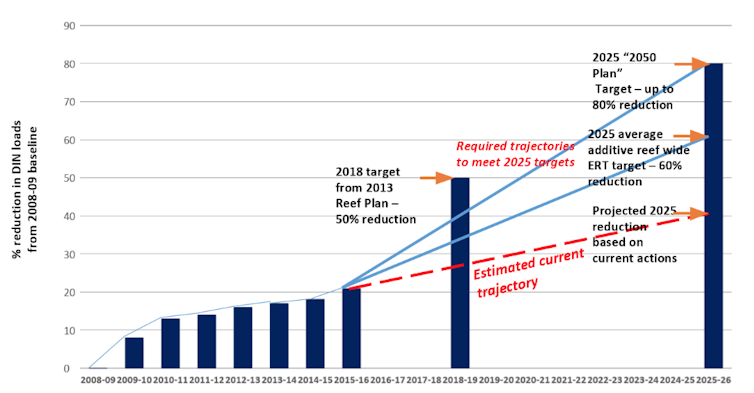

The respective load reduction targets set for 2018 and 2025 are highly unlikely to be met at current funding levels. For example, shown below are the current projections for levels of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN).

Progress on reducing total GBR wide dissolved inorganic nitrogen loads and trajectories towards targets.

CREDIT, Author provided

Progress on reducing total GBR wide dissolved inorganic nitrogen loads and trajectories towards targets.

CREDIT, Author provided

This likely failure to meet any of the targets was noted by UNESCO in 2015 and again in 2017 as a major concern, amid deliberations on whether to put the GBR on the World Heritage in Danger list. The UNESCO report criticised Australia’s lack of progress towards achieving its 2050 water quality targets and failure to pass land clearing legislation.

As the 2017 Scientific Consensus Statement also pointed out, improvements to land management oversight are “urgently needed”. Continued government spending on the same programs, at the same levels, and with no federal legislation to mandate improvements, is unlikely to bring water pollution to acceptable levels or offer significant protection to the GBR.

In contrast to the federal government, the Queensland government is taking what are likely to be more effective measures to manage water quality. These include regulations such as the revised Vegetation Management Act, which is likely to be passed by the parliament in the next few weeks; and the updated Reef Protection Act, currently out for review. Queensland is also directing funds towards pollution hotspots under the Major Integrated Projects framework.

Read more: Cloudy issue: we need to fix the Barrier Reef's murky waters

Crown-of-thorns starfish

The government’s new package has pledged A$58 million for further culling of this coral-eating animal. Yet the current culling program has faced serious criticism over its effectiveness.

Udo Engelhardt, director of consultancy Reefcare International, and a pioneer in the control of crown-of-thorns starfish, has claimed that his analysis of the culling carried out in 2013-15 in reef areas off Cairns and to the south of Cairns, reveals a “widespread and consistent failure” to protect coral cover.

Nor does there seem to have been a major independent review of the program since these findings came to light. Without one, it seems a shaky bet to assume that we will expect any more success simply by continuing to fund it.

Overcoming crown-of-thorns starfish might take some more creative thinking.

Paul Asman/Jill Lenoble/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Overcoming crown-of-thorns starfish might take some more creative thinking.

Paul Asman/Jill Lenoble/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Reef restoration

Similar question marks hover over the A$100 million being provided to harness the best science to help restore and protect the reef, and to study the most resilient corals. Like other aspects of the package, the government has not yet promised a timeline on which to roll out the funds.

While reef restoration may be significant for the long-term (decades to centuries) status of the GBR, it is hard to believe that these studies will help within the coming few decades. And even long-term success will hinge either on our ability to stabilise the climate, or on science’s ability to keep pace with the rate of future change.

In the meantime, reef restoration seems at best to be a band-aid that could preserve select tourism sites, but is inconceivable on the scale of the entire GBR.

Read more: Not out of hot water yet: what the world thinks about the Great Barrier Reef

Herein lies the most significant criticism of the new funding package. It avoids any mention of reducing Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, or of working closely with the international community to help deliver significant global reductions. Yet climate change is routinely described as the biggest threat to the reef.

The new announcement dodges that issue, while providing a moderate amount of funding for the continuation of largely unsuccessful programs. Given that the new funding is to be managed by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation – which is a charity rather than a statutory management body – we can only hope that the foundation finds new and innovative ways to improve greatly on the current efforts.

Authors: Jon Brodie, Professorial Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University