A Tasmanian Requiem is a musical reckoning, and a pathway to reconciliation

- Written by Kristyn Harman, Senior Lecturer in History; Graduate Research Coordinator, School of Humanities; Course Coordinator, Diploma of History, University of Tasmania

On December 26, 1847, a small group of Aboriginal people sat in the Lieutenant-Governor’s box at Hobart’s Theatre Royal watching a new pantomime. A local newspaper reported how “the natives … seemed gratified at their first public introduction to society in a place of amusement”. The Aboriginal spectators commanded as much, if not more, public attention than the performance itself.

More than 170 years later, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people came together at the same theatre on 13 April 2018 to witness the world premiere of A Tasmanian Requiem, an oratorio for voice and brass described as “a long-overdue mourning” for Tasmania’s “war of extermination”.

Made up of nine movements, the Requiem was created by Tasmanian-based composer and performer Helen Thomson and performed by seven singers and five brass players. Four singers represented voices from Western history, both the colonial and contemporary experience. The other three included two contemporary Aboriginal singers, representing Palawa (Tasmanian Aboriginal) Voices, and a mezzo-soprano as the Earth Voice.

This deeply moving performance could be viewed as an act of symbolic and practical reconciliation, given the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal artists and audience members. It examined the pre-colonial and colonial past while offering a road map towards a reconciled future.

Read more: Explainer: the evidence for the Tasmanian genocide

The Aboriginal audience at the Theatre Royal in 1847 had been repatriated to the Tasmanian mainland after living in exile on offshore islands following the genocidal Vandemonian War. Following the British invasion in the early years of the 19th century, war broke out between Aboriginal people and the colonists. Within two generations, the island’s Aboriginal population was dramatically reduced. By the 1830s, just a few dozen survivors remained.

A Tasmanian Requiem seeks to address this difficult history. While the program stated that “The Black War between settlers and Aborigines is unacknowledged in official Australian military history”, the war has been written about extensively. Perhaps the silence the program alludes to refers to a lack of public acknowledgement within Tasmania.

Madelena Andersen-Ward and Zoy Frangos in A Tasmanian Requiem.

Alastair Bett

Madelena Andersen-Ward and Zoy Frangos in A Tasmanian Requiem.

Alastair Bett

Traditions converging

Requiems traditionally set religious texts to music. Thomson’s musical score was inspired by existing requiems by Heinrich Schütz, Hans Werner Henze and especially Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, which combines traditional Catholic text with war poems from Wilfred Owen. These influences, as well as the music of the 16th Century Italian composer Giovanni Gabrieli, pointed purposefully to the Church’s exercise of power, as well as Tasmania’s colonial history.

The music provided a sensitive and evocative setting for the libretto, written by Greg Lehman, Frances Butler and Jim Everett-puralia meenamatta. This text featured English, Latin and Tasmanian Aboriginal language, melding Western and Aboriginal traditions, yet highlighting some dissonances between them.

This was particularly striking in the pivotal fifth movement, titled The Black War, in which insistent yet anguished Palawa voices cried repeatedly “Parrawa! Parrawa!” (“Go away! Go away!”).

Other parts of the libretto portrayed a realistic, deeply disquieting, colonial voice. Phrases such as “the government must remove the natives – if not they will be hunted down like wild beasts and destroyed!” are well known to those familiar with Tasmania’s colonial history.

The juxtaposition of Western and Aboriginal voices was complemented by music inspired by Allegri’s ever-popular Miserere and songs from wax cylinder recordings featuring Aboriginal Tasmanian Fanny Cochrane Smith, created in 1899 and held at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart. The setting of Cochrane Smith’s rendition of Spring Song in the third movement was particularly effective.

Sound and image

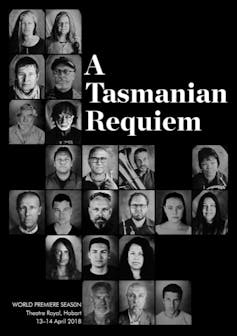

The performance’s commitment to bringing past and present together continued through the program, where 22 tin-type portraits, drawing on the early photographic technique, illustrated those involved in the production.

The program for A Tasmanian Requiem showing the tin-type portraits of the performers. Design by Heike Schmidt/Raum Studio; tintype portraits by Phillip England/Tasmanian Tintype.

A Tasmanian Requiem

The program for A Tasmanian Requiem showing the tin-type portraits of the performers. Design by Heike Schmidt/Raum Studio; tintype portraits by Phillip England/Tasmanian Tintype.

A Tasmanian Requiem

During the performance, video footage projected behind the performers provided an ever changing backdrop and visual cues for the audience. Swirling constellations alluding to genesis, kangaroos grazing in an earthly pre-invasion paradise, and a stark, brutalised Tasmanian landscape complemented the musical elements. Images of colonial sandstone buildings were interspersed with often striking images drawn from nature.

There are scarcely any images of the Vandemonian War itself. To illustrate this conflict, filmmakers Julie Gough and Michael Gissing used colonial texts symbolically, and, less successfully, visual imagery borrowed from mainland Australian conflicts. Footage of Anzac parades and monuments highlighted another absence - Australia’s lack of public holidays, parades and statues to commemorate the colonial wars fought on its own soil. Some of these diverse materials were awkwardly collaged, which detracted from the overall experience, and there were some technical visual challenges.

Despite this, the world premiere of A Tasmanian Requiem could hardly have been better timed. Public consultations are currently underway over the future of prime land at Hobart’s waterfront, with MONA (Museum of Old and New Art) advocating for an art park acknowledging the Vandemonian War to promote healing and reconciliation. A Tasmanian Requiem has much to offer to this conversation. It shows what a historical reckoning, and reconciliation, could look - and sound - like.

Authors: Kristyn Harman, Senior Lecturer in History; Graduate Research Coordinator, School of Humanities; Course Coordinator, Diploma of History, University of Tasmania