MRKH syndrome, when a woman's uterus never develops

- Written by Emanuele Pelosi, Senior Research Officer, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland

Reaching reproductive age is an important milestone, and for women this is usually marked by their first period.

But for some young women, it never comes. In medical terms this is called primary amenorrhea, and one of the major causes is a congenital condition called Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser (MRKH) syndrome.

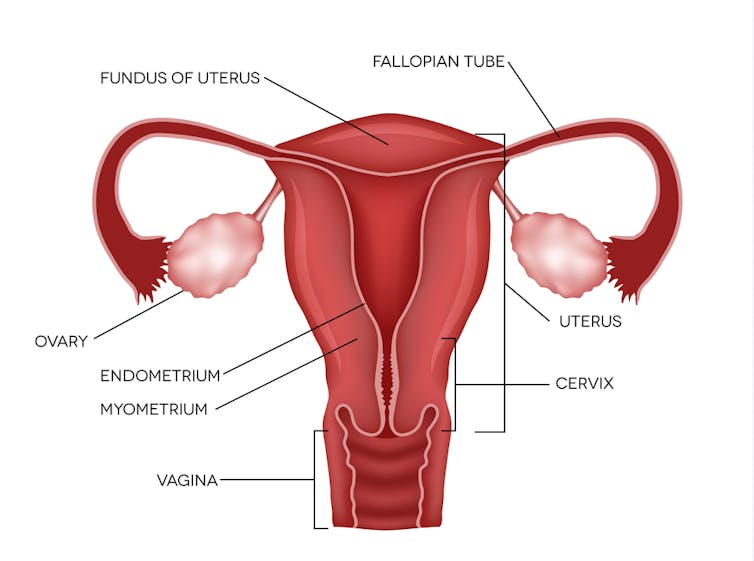

In MRKH syndrome, named after the four specialists who collectively over 100 years contributed to the description and understanding of the syndrome, the female reproductive tract never fully develops. The uterus, cervix, and upper vaginal canal are underdeveloped or not present.

MRKH Syndrome occurs in one in every 4,500-5,000 women, and can present in two forms:

type I, which involves underdevelopment or absence of the uterus and vagina

type II, which is also associated with other malformations, typically of the kidney and spine.

Usually, affected women won’t be aware of the condition until puberty, when their first period never comes. A first physical examination would reveal an absent or underdeveloped vagina. If hormone levels are normal, then MRKH syndrome is suspected, and medical imaging can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

In MRKH syndrome the upper vagina, cervix and entire uterus never develop.

from www.shutterstock.com

In MRKH syndrome the upper vagina, cervix and entire uterus never develop.

from www.shutterstock.com

Management

Surgery, or therapy with vaginal dilators (an implement that causes elongation in the vaginal canal when inserted and pressure is applied) can be used to expand or create a vagina. But the absence of a uterus means that a biological pregnancy is not possible.

It’s possible for most women with MRKH syndrome to have biological children where assisted reproductive technology and surrogacy are an option.

Being diagnosed with MRKH syndrome can be very distressing, and usually leaves the affected woman with more questions than answers.

Causes

The causes of MRKH syndrome are still unknown. Although some cases could be the result of environmental exposures, researchers have not found a clear association.

Recent studies have shown that there may be a genetic cause, but so far no single gene or mutation has been identified as being responsible for MRKH. It may be that multiple factors and genes are involved.

Read more: Unusual conditions: what are gigantism and acromegaly?

Several genes are currently being investigated, but research on MRKH syndrome is still deemed challenging due to its rarity and emotional impact. These make it difficult to recruit patients for genetic analysis.

Nonetheless, it is crucially important to study the genetics of MRKH and to identify the genetic variants associated with it, so as to provide explanations of the causes and implement therapeutic strategies. This is important for several reasons:

We need to better understand the genes and pathways that enable genitalia to grow and function, and how these genes and pathways interfere with uterine and vaginal development when interrupted

If we understand the causes, we can find ways to manage the clinical and psychological well-being of affected women and describe clearly the diagnosis and management. A recent survey showed that most participants felt MRKH was not explained in a way they understood

With more awareness, better psychological and emotional support can be made available in the form of peer support networks and guidance from health-care professionals to both the patients and their families. With better support, women would be less likely to feel isolated and traumatised by an MRKH diagnosis.

Where to from here?

The Sisters for Love MRKH Foundation, founded by two women with MRKH syndorme, Alison Hensley and Jaqi Quinlan, is a support group that aims to connect, inform, and help MRKH women and their families.

Read more: Unusual conditions: what is Rapunzel syndrome and why do some people eat hair?

In association with Sisters for Love MRKH Foundation, I’m currently undertaking research alongside Professor Peter Koopman at the University of Queensland, and collaborators at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. We’re aiming to identify the genetic causes of MRKH syndrome and to provide women with MRKH with the answers they seek.

The results of this project may help doctors provide a more detailed diagnosis, thus improving the diagnostic experience for the patient, and also providing women with MRKH and their families an enhanced support system.

For more information and enquiries regarding research and recruitment, please contact me here. For information and support regarding MRKH, visit the Sisters for Love MRKH Foundation.

Authors: Emanuele Pelosi, Senior Research Officer, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland