Child tooth decay is on the rise, but few are brushing their teeth enough or seeing the dentist

- Written by Anthea Rhodes, Paediatrician and Lecturer in Child and Adolescent Health, Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne

One-third of preschoolers have never seen a dentist and most parents believe children don’t need to see one before they’re three years old. Yet one-quarter of Australian children have tooth decay that requires filling by early primary school. One in ten require an extraction.

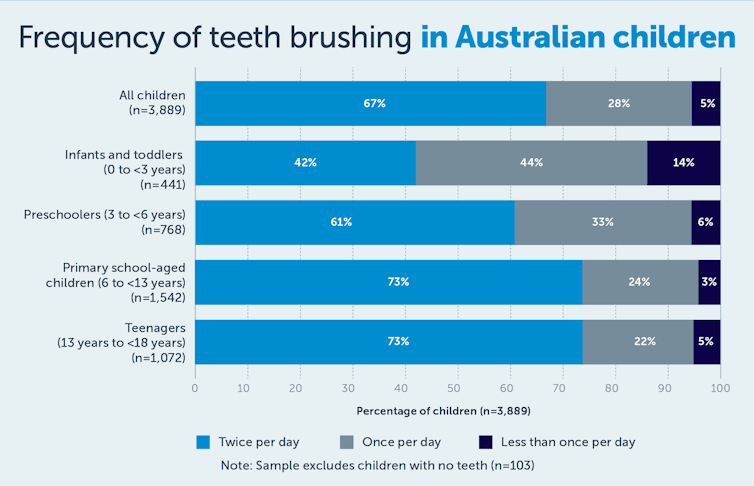

Results released today from the latest Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll also reveal one in three children (33%) aren’t brushing their teeth twice a day and almost half of parents (46%) don’t know that tap water is better for teeth than bottled water.

Read more: Four myths about water fluoridation and why they're wrong

Rates of tooth decay are on the rise in Australia, particularly among young children. More than 26,000 Australians under the age of 15 are admitted to hospital to treat tooth decay every year. This makes it the highest cause of acute, preventable hospital stays.

Untreated dental disease can cause chronic infection and pain. This can affect a child’s ability to eat, play and learn, and so impact their growth, development and quality of life. It’s also linked to long-term health outcomes like heart disease and diabetes.

Our poll shows that many parents, despite meaning well, lack the basic knowledge to prevent tooth decay in their children. Others are confused when it comes to recommendations about brushing teeth, diet and when to see the dentist for a check-up.

When a child should see the dentist

Children should visit the dentist when their first tooth comes through, or at 12 months of age. Our poll found only 17% of children had seen a dentist by the age of two.

Early visits are essential to provide parents with support and education to help keep their children’s teeth and gums healthy, before teeth break down and start to cause trouble. Children as young as two can require treatment in hospital for severely broken down, infected and painful teeth.

Tooth decay develops over time and early decay can be hard to spot. Starting dental check-ups from 12 months will help identify any red flags and allow parents to make changes to diet and lifestyle. Regular check-ups allow decay to be detected and treated early and more complex and costly treatments avoided. Some children require check-ups more often than others and parents should consult with their dentist on how often their child should go.

Tooth decay can develop quickly and be hard to stop.

from shutterstock.com

Tooth decay can develop quickly and be hard to stop.

from shutterstock.com

Seeing a dentist can be costly though. In our poll, one in five parents cited cost as a reason for delaying a visit to the dentist. But many were unaware of the free dental services that may be available to their children. All Australian states and territories offer public dental care to children at no or minimal cost, up to a certain age.

In addition to this, the federal Child Dental Benefits Schedule provides eligible families with up to A$1,000 worth of treatment over two years. This can be used for private as well as public dental services for children aged 2-17. All children in families receiving Parenting Payment or Family Tax Benefit Part A are eligible for the program. One-quarter of eligible families we surveyed weren’t aware of the program.

Read more: Kids' vitamin gummies: unhealthy, poorly regulated and exploitative

Ultimately, only dental professionals are registered to provide dental examinations to children. But young children often see a range of healthcare providers for different reasons. Every visit to the GP, pharmacist or child health nurse is an opportunity for dental education and decay prevention. GPs and child health nurses can also help direct families to appropriate and affordable dental services.

When should children brush their teeth?

While brushing once a day is better than not at all, brushing teeth twice a day further reduces the chance of tooth decay. Our poll found one-third of children aren’t brushing their teeth often enough, with one in four parents believing once a day is adequate.

RCH Child Health Poll, Author provided (No reuse)

Dentists recommend using a cloth to clean a baby’s gums from birth, moving onto a toothbrush with water when the first tooth erupts. A pea-sized amount of children’s strength toothpaste is recommended from 18 months of age. Children can use adult-strength toothpaste from the age of six. Parents should help children with brushing their teeth up to the age of eight to ensure it’s done properly.

Most children will begin losing their primary teeth, also known as “baby” or “milk” teeth, from around the age of six. The last falls out about age 12. One in five parents indicated they thought it didn’t matter if young children got tooth decay since their baby teeth fall out anyway.

RCH Child Health Poll, Author provided (No reuse)

Dentists recommend using a cloth to clean a baby’s gums from birth, moving onto a toothbrush with water when the first tooth erupts. A pea-sized amount of children’s strength toothpaste is recommended from 18 months of age. Children can use adult-strength toothpaste from the age of six. Parents should help children with brushing their teeth up to the age of eight to ensure it’s done properly.

Most children will begin losing their primary teeth, also known as “baby” or “milk” teeth, from around the age of six. The last falls out about age 12. One in five parents indicated they thought it didn’t matter if young children got tooth decay since their baby teeth fall out anyway.

Parents should help children brush their teeth until they are about eight years old.

from shutterstock.com

Primary teeth may be temporary, but they need to be strong and healthy so children can chew, speak and smile with confidence. They also act as “space savers” for adult teeth. If a child prematurely loses a milk tooth, the tooth beside it may drift into the empty space, preventing the adult tooth from erupting into its proper place.

What about diet?

Our poll found one in four children under five years are put to bed most days of the week with a bottle containing milk-based or sweetened drinks. This practice is strongly linked to tooth decay due to the prolonged exposure of teeth to sugar during sleep. Babies should finish their bottles before being put into bed. From around one year of age, they should be encouraged to drink from a cup instead.

But sugar-sweetened drinks are not the only worry when it comes to teeth. In recent years, bottled water intake in kids has increased considerably, and half of parents think bottled water may be better for teeth than tap water. More than 90% of Australians have access to fluoridated tap water, which helps strengthen teeth and prevent decay. Unlike tap water, most bottled water in Australia contains very little fluoride, making it a less healthy choice for teeth.

Most parents know consuming sugary food and drinks can contribute to tooth decay. But more than 70% of Australian children and adolescents exceed World Health Organisation recommendations for sugar intake and many parents report finding it hard to know how much added sugar is in food.

Read more:

Health Check: how much sugar is it OK to eat?

The recommended maximum daily intake of added sugar for children is around five teaspoons. According to parents polled, one-third of Aussie kids have sugar-sweetened drinks most days of the week, including one in five preschoolers. A 375ml can of soft drink contains around nine teaspoons of sugar.

It’s not just up to parents and dentists to tackle the growing problem of child tooth decay. Other healthcare providers and policymakers have a critical role to play. We need to make sure all parents have access to the right information and support to make healthy choices for their children’s teeth every day from birth.

Parents should help children brush their teeth until they are about eight years old.

from shutterstock.com

Primary teeth may be temporary, but they need to be strong and healthy so children can chew, speak and smile with confidence. They also act as “space savers” for adult teeth. If a child prematurely loses a milk tooth, the tooth beside it may drift into the empty space, preventing the adult tooth from erupting into its proper place.

What about diet?

Our poll found one in four children under five years are put to bed most days of the week with a bottle containing milk-based or sweetened drinks. This practice is strongly linked to tooth decay due to the prolonged exposure of teeth to sugar during sleep. Babies should finish their bottles before being put into bed. From around one year of age, they should be encouraged to drink from a cup instead.

But sugar-sweetened drinks are not the only worry when it comes to teeth. In recent years, bottled water intake in kids has increased considerably, and half of parents think bottled water may be better for teeth than tap water. More than 90% of Australians have access to fluoridated tap water, which helps strengthen teeth and prevent decay. Unlike tap water, most bottled water in Australia contains very little fluoride, making it a less healthy choice for teeth.

Most parents know consuming sugary food and drinks can contribute to tooth decay. But more than 70% of Australian children and adolescents exceed World Health Organisation recommendations for sugar intake and many parents report finding it hard to know how much added sugar is in food.

Read more:

Health Check: how much sugar is it OK to eat?

The recommended maximum daily intake of added sugar for children is around five teaspoons. According to parents polled, one-third of Aussie kids have sugar-sweetened drinks most days of the week, including one in five preschoolers. A 375ml can of soft drink contains around nine teaspoons of sugar.

It’s not just up to parents and dentists to tackle the growing problem of child tooth decay. Other healthcare providers and policymakers have a critical role to play. We need to make sure all parents have access to the right information and support to make healthy choices for their children’s teeth every day from birth.

Authors: Anthea Rhodes, Paediatrician and Lecturer in Child and Adolescent Health, Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne