Australia is missing the Closing the Gap employment target by decades

- Written by Zoe Staines, Research Consultant; Research Assistant, Queensland University of Technology

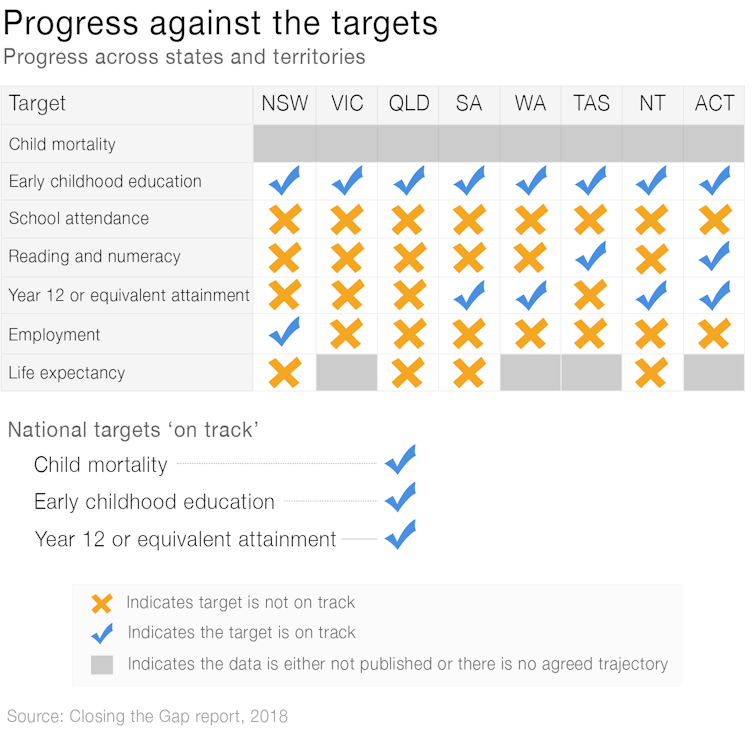

Australia is missing its target to halve the unemployment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia by several decades, according to the latest Closing the Gap report.

The report also highlights many other problems with current Closing the Gap targets. For instance, the unemployment target misses other aspects of economic life, such as income. The targets need to be rethought so that they address economic well-being and more closely guide strategy and policies on the ground.

Read more: Closing the Gap results still lag, as Shorten pledges compensation fund for Stolen Generations

The unemployment rate for Indigenous Australians is going down. But 2016 Census data show that it will take until 2031 to halve the gap, and until about 2051 to close the gap entirely. Even New South Wales, which leads Australia on this measure, won’t meet the target until about 2026.

One reason why some states are doing better in tackling the unemployment gap is that different opportunities are available for urban and rural Australians. In 2014/15, only 5% of the NSW Indigenous population lived in remote areas. This compares to 21% nationally, 79% in the Northern Territory and 19% in Queensland.

CC BY-ND

Under the Indigenous Procurement Policy, 3% of all federal procurement contracts go to Indigenous businesses. This is a big part of the federal government’s plan to achieve the employment target.

However, while there may be some success stories, a recent report also warned that “the policy’s target measurement system greatly exaggerates its success”.

For instance, in 2015-16 Indigenous suppliers won 2.9% of government contracts but these contracts accounted for only 0.94% of total procurement spending.

Read more:

Radical rethink of Closing the Gap required, despite some progress

The latest Closing the Gap report highlights the continued importance of Indigenous leadership in this space and the need for government to actually listen and truly partner, rather than just talk about it.

Only through empowerment and ownership by Indigenous Australians will we see serious improvements against a revised Closing the Gap framework, or any other standard for that matter. Mere rhetoric is not, and never will be, enough.

While Closing the Gap focuses on hitting a target employment rate, there are other aspects to economic well-being that are not considered.

The framework fails to address the widening gap in weekly personal income between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia, for example. This shows that even if employment rates are improving, Indigenous Australians are still earning comparatively less.

Economic well-being also collides with other facets of well-being in a number of ways. For instance, an adequate income means earning enough money to access quality health care and education. But it’s also important to derive satisfaction and meaning from employment.

Read more:

Three reasons why the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians aren't closing

There is also no clear strategy for how the targets filter down into ground-level approaches that are evidence-based and actually work. The federal government’s Indigenous Advancement Strategy tried to link activities to outcomes that aligned with the Closing the Gap targets, but was found to have performed poorly across a number of areas.

Without a stronger evidence base and a clearer strategy for how the targets are meant to inform on-the-ground policies and programs, we simply don’t know which approaches to amplify and which to abandon.

Read more:

Closing the gap on Indigenous education must start with commitment and respect

The current process to refresh the Closing the Gap targets and framework is under way and might consider some of these issues. However, it already faces problems with poor consultation and partnership.

This is ironic, given the repeated sentiments of the last ten years of Closing the Gap reports that relationships are being strengthened.

Although the latest report has shown that some areas are improving, there are many more metrics that show little or no change.

CC BY-ND

Under the Indigenous Procurement Policy, 3% of all federal procurement contracts go to Indigenous businesses. This is a big part of the federal government’s plan to achieve the employment target.

However, while there may be some success stories, a recent report also warned that “the policy’s target measurement system greatly exaggerates its success”.

For instance, in 2015-16 Indigenous suppliers won 2.9% of government contracts but these contracts accounted for only 0.94% of total procurement spending.

Read more:

Radical rethink of Closing the Gap required, despite some progress

The latest Closing the Gap report highlights the continued importance of Indigenous leadership in this space and the need for government to actually listen and truly partner, rather than just talk about it.

Only through empowerment and ownership by Indigenous Australians will we see serious improvements against a revised Closing the Gap framework, or any other standard for that matter. Mere rhetoric is not, and never will be, enough.

While Closing the Gap focuses on hitting a target employment rate, there are other aspects to economic well-being that are not considered.

The framework fails to address the widening gap in weekly personal income between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia, for example. This shows that even if employment rates are improving, Indigenous Australians are still earning comparatively less.

Economic well-being also collides with other facets of well-being in a number of ways. For instance, an adequate income means earning enough money to access quality health care and education. But it’s also important to derive satisfaction and meaning from employment.

Read more:

Three reasons why the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians aren't closing

There is also no clear strategy for how the targets filter down into ground-level approaches that are evidence-based and actually work. The federal government’s Indigenous Advancement Strategy tried to link activities to outcomes that aligned with the Closing the Gap targets, but was found to have performed poorly across a number of areas.

Without a stronger evidence base and a clearer strategy for how the targets are meant to inform on-the-ground policies and programs, we simply don’t know which approaches to amplify and which to abandon.

Read more:

Closing the gap on Indigenous education must start with commitment and respect

The current process to refresh the Closing the Gap targets and framework is under way and might consider some of these issues. However, it already faces problems with poor consultation and partnership.

This is ironic, given the repeated sentiments of the last ten years of Closing the Gap reports that relationships are being strengthened.

Although the latest report has shown that some areas are improving, there are many more metrics that show little or no change.

Authors: Zoe Staines, Research Consultant; Research Assistant, Queensland University of Technology