Something is missing from the public interest journalism debate

- Written by Misha Ketchell, Editor, The Conversation

Let’s start with a few things on which we can all agree, chief among them that public interest journalism is a Good Thing. The fourth estate has a crucial role in holding power to account. The big stories that journalists uncover can spark meaningful change: Watergate, or the Moonlight State corruption revelations in Queensland, or the Spotlight team at the Boston Globe that uncovered sexual abuse by the clergy.

As the senate inquiry on the future of public interest journalism in Australia heard the year, there is also broad agreement that this type of activity is now in peril. Putting public broadcasters to one side, all the big commercial institutions that used to produce public interest journalism are increasingly starved of cash as Google and Facebook relentlessly hoover up advertising dollars (all while paying depressingly little tax).

According to the MEAA, more than three thousand Australian journalists have lost their jobs since 2011 and this mirrors a global trend. Meanwhile, pretty much every media organisation is struggling with precarious funding. Many new players, as well as many once great and powerful media companies, now devote much of their time to discussing paywall strategy and begging readers for donations. Time they once spent scaring the wits out of politicians and business leaders is now spent fighting for survival.

I think most people broadly understand this, and share in an increasing sense of the urgency to do something to disrupt the dominance of spin, misinformation and fake news.

But for all of this, I don’t think our understanding of public interest journalism captures anything close to the full spectrum of what has already been lost and needs to be recreated. As 2017 draws to a close I’d like to propose a fuller and more nuanced account of the ways in which public interest journalism serves the public.

It’s hard to talk about what isn’t happening, so I’ll start with my local newspaper, The Age. These days it’s light as a feather compared the brick of a decade ago. But, interestingly, what’s missing is not the investigative reporting. That vital work is still being done, and to a very high standard: think of the Richard Baker, James Massola and Nick McKenzie story about Chinese political donor, Huang Xiangmo that led to the demise of Senator Sam Dastyari, or the work led by Adele Ferguson and the ABC’s Four Corners on the Commonwealth Bank, or pretty much anything by the Sydney Morning Herald’s Kate McClymont.

What’s missing is pretty much everything else that has been dropped to balance the books. Essays and reviews of significant new art and music and theatre used to demand a separate fat weekend supplement. Coverage of the city, of local councils, of state politics is so much thinner than it used to be. Reporters are clearly no longer spending as much time with ethnic and community groups and getting to understand their issues and concerns. Reports from rural areas and the outer suburbs are rare. The thoughtfully presented science stories, the analysis of new research in health, the balanced and informed cultural commentary, the stories that hold up a mirror to our society and help people form more nuanced, kinder views: that’s what is missing.

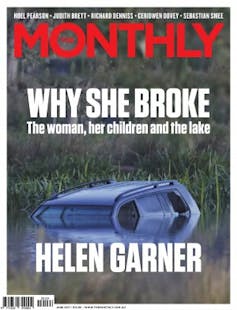

This year Helen Garner wrote a Walkley-award winning piece of journalism about a 35-year-old South Sudanese woman who drove into a dam and killed three of her children. If you just read news reports of tragedy it might elicit little more than a gasp, a wave of anger of sympathy, then a flick of the page. But Garner wanted to know more. Her story on Akon Goude was a vital piece of public interest journalism, but it won’t change a single government policy. It doesn’t right a wrong and it doesn’t expose corruption.

I’m mentioning this story because others of this type, let’s call them curiosity journalism, were once much more common in the media. Now media companies rarely have the money to pay for this sort of work. It’s often seen as an indulgence, and a risk.

Why does it matter? Because so much of the shrill and often partisan political debate we see in the media can be linked to an increasing lack of nuance in the way evidence, and stories, are presented to us. Stories stripped of context, without a clear explanation of the background, without a clear understanding of the key characters.

Clean information is as important to democracy as clean water is to health. But clean information is not just facts. Facts are apt to mislead and clean information requires journalists who are committed to providing a full picture. This is where The Conversation makes a significant, and not terribly well understood, contribution.

We don’t try to duplicate the big investigations or the work of literary journalists. But we do try to add to the media ecosystem and deepen understanding. We do this by working with academics to provide reliable information that reports on new research and explains and informs beyond the headlines.

We do this across the sciences, the humanities, the arts. Everything we do is free to other media outlets to republish, to better inform their readers and deepen their coverage. We aim to provide useful information when readers want it, whether it be an explanation of how section 44 of the Constitution works or an essay on why older gay men don’t support same-sex marriage or an explanation for a child on how X-rays work.

This type of reliable and well-researched information is vital to the public interest. It helps Australians understand politics and cast a more informed vote. It also helps us decide what to eat to stay healthy, or how to keep our children safe online, or how to avoid the risks of problem gambling. It provides insights that help us understand our environment, our culture, our history.

This unique brand of academic journalism is pitched to add to the work of other media outlets, not usurp it. We want to make a contribution, not build a media empire. That’s why we follow the news closely and commission stories to help readers make sense of what is going on. And it’s why we work closely with the ABC to provide analysis which adds to its news reporting – as well as with hundreds of other media outlets across Australia and the world.

I hope, that as we move into 2018, we can build a better understanding of the ecosystem that supports public interest journalism. If we want to preserve it, we first need to really understand exactly what it is.

This year Helen Garner wrote a Walkley-award winning piece of journalism about a 35-year-old South Sudanese woman who drove into a dam and killed three of her children. If you just read news reports of tragedy it might elicit little more than a gasp, a wave of anger of sympathy, then a flick of the page. But Garner wanted to know more. Her story on Akon Goude was a vital piece of public interest journalism, but it won’t change a single government policy. It doesn’t right a wrong and it doesn’t expose corruption.

I’m mentioning this story because others of this type, let’s call them curiosity journalism, were once much more common in the media. Now media companies rarely have the money to pay for this sort of work. It’s often seen as an indulgence, and a risk.

Why does it matter? Because so much of the shrill and often partisan political debate we see in the media can be linked to an increasing lack of nuance in the way evidence, and stories, are presented to us. Stories stripped of context, without a clear explanation of the background, without a clear understanding of the key characters.

Clean information is as important to democracy as clean water is to health. But clean information is not just facts. Facts are apt to mislead and clean information requires journalists who are committed to providing a full picture. This is where The Conversation makes a significant, and not terribly well understood, contribution.

We don’t try to duplicate the big investigations or the work of literary journalists. But we do try to add to the media ecosystem and deepen understanding. We do this by working with academics to provide reliable information that reports on new research and explains and informs beyond the headlines.

We do this across the sciences, the humanities, the arts. Everything we do is free to other media outlets to republish, to better inform their readers and deepen their coverage. We aim to provide useful information when readers want it, whether it be an explanation of how section 44 of the Constitution works or an essay on why older gay men don’t support same-sex marriage or an explanation for a child on how X-rays work.

This type of reliable and well-researched information is vital to the public interest. It helps Australians understand politics and cast a more informed vote. It also helps us decide what to eat to stay healthy, or how to keep our children safe online, or how to avoid the risks of problem gambling. It provides insights that help us understand our environment, our culture, our history.

This unique brand of academic journalism is pitched to add to the work of other media outlets, not usurp it. We want to make a contribution, not build a media empire. That’s why we follow the news closely and commission stories to help readers make sense of what is going on. And it’s why we work closely with the ABC to provide analysis which adds to its news reporting – as well as with hundreds of other media outlets across Australia and the world.

I hope, that as we move into 2018, we can build a better understanding of the ecosystem that supports public interest journalism. If we want to preserve it, we first need to really understand exactly what it is.

Authors: Misha Ketchell, Editor, The Conversation

Read more http://theconversation.com/something-is-missing-from-the-public-interest-journalism-debate-89369