As Socceroos face moment of truth, let's remember our football triumph of 1967

- Written by Roy Hay, Honorary Fellow, Deakin University

November 14 marks 50 years since the Australian men’s national football team – which was not yet known as the Socceroos – won its first international trophy in Saigon in the middle of the Vietnam War.

This remarkable triumph, and the young men who made it happen, have never been properly and collectively recognised. Eight of those who took part went on to help Australia qualify for the World Cup in 1974; the collective spirit forged in Vietnam was one of the keys to that success.

As the national team of today prepares for its last-chance World Cup qualifier against Honduras, it would do well to draw inspiration from this episode – despite its exclusion from the national narrative.

Football played amid fighting

Captain Johnny Warren leads the team out at the opening ceremony.

Johnny Warren Collection, National Museum of Australia

Captain Johnny Warren leads the team out at the opening ceremony.

Johnny Warren Collection, National Museum of Australia

In 1967, at the height of the Vietnam War, the Holt government agreed it would be a good idea if the national football team took part in a tournament in Vietnam to boost morale in some of the nations involved in the war.

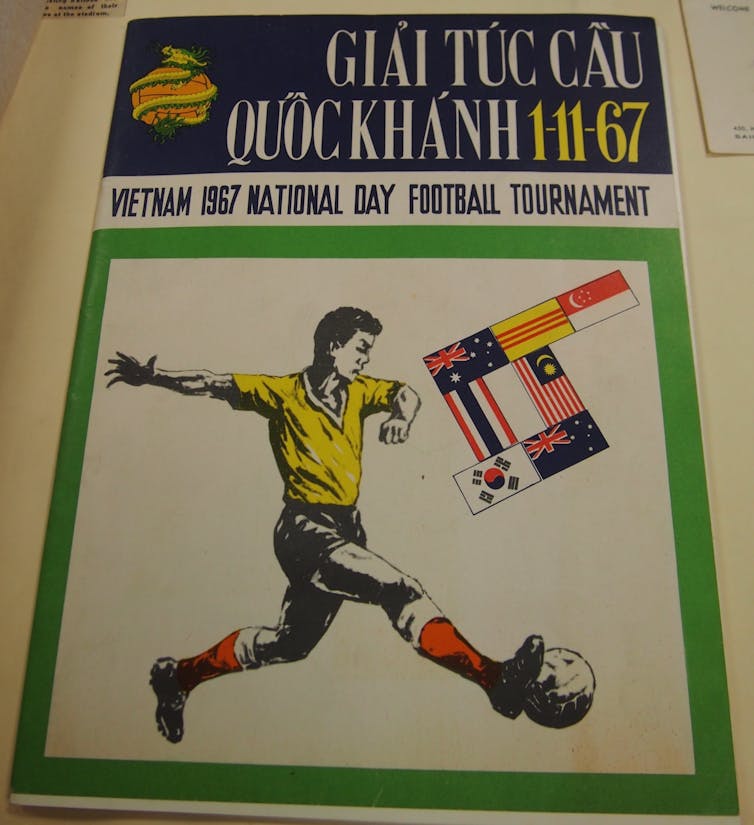

Football diplomacy in Asia preceded ping-pong diplomacy by a few years. So, Australia set off for the Vietnam National Day Football Tournament in Saigon at the start of November 1967.

In many ways, it was a strange and frightening experience for the Australians. They were pitched into the middle of a war that was beginning to become unpopular at home.

Australian captain Johnny Warren recalled the team would be eating with soldiers in their mess and then going to play football, while their compatriots went off to fight. Players were warned by security on arrival not to spend time with Americans, because the latter were prime targets for the Viet Cong.

Eight teams from nations involved in the war took part. Australia, South Vietnam, New Zealand and Singapore made up Group A; South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand and Hong Kong were in Group B.

After a tough tournament, Australia came up against South Korea in the final. The match nearly did not take place after the team was informed there was no space in the stadium for the Australian military personnel who had been a huge support to the players on and off the field. The Australians threatened not to take part.

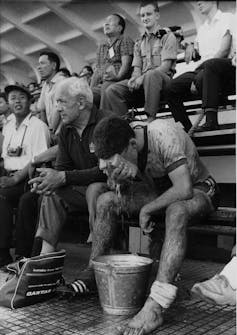

Ray Richards exhausted on the bench alongside Lou Lazzari.

Laurie Schwab Collection, Deakin University Library

Ray Richards exhausted on the bench alongside Lou Lazzari.

Laurie Schwab Collection, Deakin University Library

As it turned out, the service personnel were allowed in and the rest of the crowd supported Australia rather than the Koreans, much to the Australians’ surprise. South Korea scored in the first minute, but the Australians responded brilliantly. Billy Vojtek scored a wonderful solo goal after 36 minutes, and Attila Abonyi and Warren added the others in a 3-2 win.

Though mortar batteries could be heard in Saigon on most days, it was said at the time that there were so many Viet Cong at the matches there was no trouble inside the stadium.

The day after the victory, the Australians went off to visit the troops in Vung Tau and played a game against them. On the way home, there were matches with Indonesia and New Zealand in Malaysia.

Australia played ten games on the tour and won them all. The camaraderie in the face of adversity was an important element in the mindset that eventually helped them to qualify for the 1974 World Cup.

Why Australia’s victory didn’t resonate

However, it would have taken a miracle for Australia’s triumph in Vietnam to become part of the national sporting narrative – far less the national story.

The anti-Vietnam War movement, the failure to qualify for the World Cup in 1970, the involvement with the Oceania Confederation of FIFA and the opposition of the Asian Football Confederation to Australia’s membership, the triumph of Gough Whitlam and Labor: all of these played a part in reducing its prominence.

In addition, football did not promote itself or its triumphs effectively following the victory in Vietnam in 1967.

Even the success of Rale Rasic’s team in qualifying for the 1974 World Cup – though Rasic himself paid homage to Joe Vlasits, the coach in 1967, and his work – resulted in the concentration on the experience of another close-knit group and its difficulties. The Vietnam tournament was relegated to a precursor rather than an achievement in its own right.

The Tet offensive began only a couple of months after the team returned home. It marked an escalation in the war that impinged on anti-war sentiment in Australia. It is true that the large-scale anti-war movements developed later, but there was little political traction in a sporting victory in support of Australia’s involvement in the war.

Parliament was not sitting when the 1967 tournament victory was achieved, nor when the team returned home. So, there was little opportunity at the time for any public recognition by either the government or Labor, whose opposition to continued participation in the Vietnam War was hardening.

Furthermore, Prime Minister Harold Holt’s disappearance on December 17 and its aftermath occupied public attention.

The official tournament program.

Johnny Warren Collection, National Museum of Australia

The official tournament program.

Johnny Warren Collection, National Museum of Australia

What happened next?

Australia’s failure to qualify for the World Cup in 1970 removed what would have been a huge boost for the game. The tortuous qualifying campaign and the narrow dimensions of the capitulation at the final hurdle in 1969 resonated with the football community, but hardly outside it.

Football remained the game of “sheilas, wogs and poofters” – as Warren’s autobiography famously put it.

Throughout the 1970s, the Asian Football Confederation was ambivalent about – if not hostile to – full membership for Australia. For its part, Australia was divided on the value of an Asian link, though it had become aware that Oceania was not the answer. So, promoting a victory over Southeast Asia’s best in Vietnam was not something the Asian Football Confederation or football’s governing body in Australia was likely to do.

The rise in Labor’s fortunes under Whitlam and Rasic’s appointment as national coach in 1970 meant that victories under the Holt government would not be trumpeted. Forgetting came quickly.

Real though they were, it was not just the bias against the game in Australia and the existence of other football codes that account for the absence of this triumph against the odds in the national story.

The game itself and its organisation was only nominally national, even though it was ahead of the other codes in this respect. It was to be another decade before a national league was established – that too was ahead of its time, and somehow almost “un-Australian” in 1977.

But that is no reason why the Australians of 1967 (or those who went back to Vietnam in 1970 and 1972) should be forgotten and unrecognised today. They deserve public acclaim for what they did, when they did it, and the circumstances in which they did it.

These men were not servicemen; they did not face the kinds of battle that young Australian infantry went through. They have never claimed that their experience matched that of the servicemen and women they met in Vietnam. But they should be a part of the national story.

Authors: Roy Hay, Honorary Fellow, Deakin University