Australia's species need an independent champion

- Written by Euan Ritchie, Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

Furore erupted last week among many Australians who care for our native species.

First we heard that land clearing in Queensland soared to a staggering 400,000 or so hectares in 2015-16, a near 30% increase from the previous year. Second, the federal government’s outgoing Threatened Species Commissioner, Gregory Andrews, implied on national radio that land clearing was not a pressing issue for Australia’s threatened species.

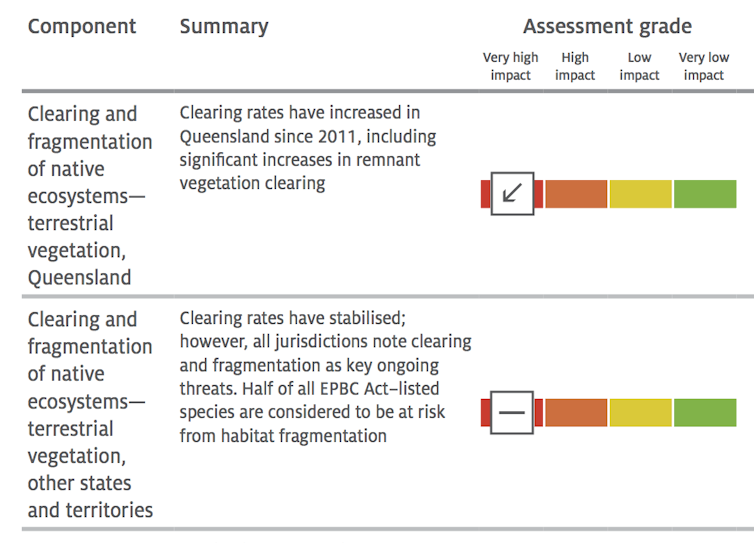

This is a troubling public message, particularly as the government’s own State of the Environment Report 2016 lists “clearing, fragmentation and declining quality of habitat” as a primary driver of biodiversity decline across the continent.

What’s more, loss of vegetation cover can exacerbate threats to wildlife, by making it easier for cats and other invasive predators to kill native animals.

Habitat loss and fragmentation are major threats to Australian biodiversity. The down arrow represents a deteriorating trend and the straight line represents a stable trend.

State of the Environment Report 2016 - Biodiversity section

Habitat loss and fragmentation are major threats to Australian biodiversity. The down arrow represents a deteriorating trend and the straight line represents a stable trend.

State of the Environment Report 2016 - Biodiversity section

These comments highlight key issues with the Threatened Species Commissioner’s current remit, made more pressing due to timing: the federal government will soon appoint a new commissioner, a “TSC 2.0”, if you will.

Threatened Species Commissioner 1.0

The commissioner’s role was established in 2014 to address the dire state of threatened species; a key initiative of the then environment minister, Greg Hunt. The remit was sixfold, including bringing a new national focus to conservation efforts; raising awareness and support for threatened species in the community; and taking an evidence-based approach to ensure conservation efforts are better targeted and co-ordinated and more effective.

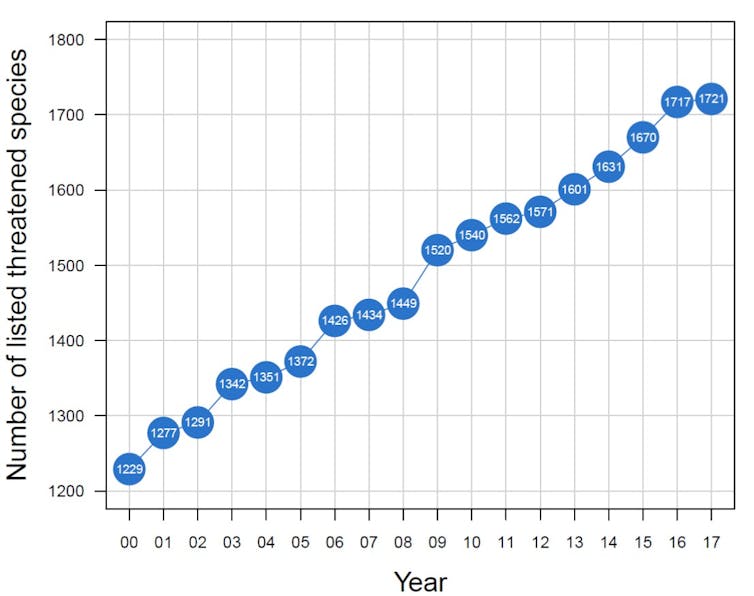

The increasing number of species listed as threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Some 492 species have been added since 2000.

Source: Federal Department of Environment and Energy

The increasing number of species listed as threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Some 492 species have been added since 2000.

Source: Federal Department of Environment and Energy

Did TSC 1.0 meet the objectives?

We can confidently say “yes” in relation to the objectives of collaboration, public awareness and promotion of threatened species conservation. Andrews travelled widely and engaged directly with stakeholders, maintained active social media feeds, developed a YouTube channel, and had numerous media engagements.

Also laudable was the 2015 Threatened Species Summit, attended by some 250 delegates from a diverse set of stakeholders, which garnered significant media coverage.

But elsewhere progress has been mixed. The development of the Threatened Species Strategy is welcome, but the plan does not go nearly far enough. Key targets by 2020 are improvements in the population trajectories of 20 mammals, 20 birds and 30 plants. But this represents a mere 4% of Australia’s threatened species, excluding all threatened reptiles, amphibians, fishes and invertebrates, and most of our threatened flora.

The focus on threatening processes is equally narrow. The science tells us that habitat loss is a top threat to Australia’s biodiversity. Land clearing has been listed as a key threatening process under federal legislation since 2001.

Yet the Threatened Species Strategy mentions land clearing zero times and habitat loss just twice. Feral cats, on the other hand, are mentioned 78 times, with the plan overwhelmingly focused on culling this one invasive species. Other major introduced pests - foxes, rabbits, feral pigs and goats - are mentioned 10 times between them.

Feral cats are a key threat to mammals, reptiles and birds, but not to Australia’s 1,272 threatened plants.

Feral cats are a key threat to mammals, reptiles and birds, but not to Australia’s 1,272 threatened plants.

An on-ground focus and mobilising of financial and logistical resources to support threatened species recovery was a welcome development during Andrews’s tenure. His second progress report cites AU$131 million in funding for projects in support of threatened species since 2014.

This is a significant sum. But it is just 0.017% of the government’s AU$416.9 billion annual revenue – well short of what’s needed to reverse species declines.

Likewise, funding for threatened species must be better targeted. Of the 499 projects cited in the TSC second progress report, 361 were those of the Green Army and 20 Million Trees programs (costing AU$78 million, 60% of total funding). Neither program is specifically devoted to threatened species, and their benefit in this regard is doubtful.

The next commissioner’s checklist

Australians and democratic societies should have access to reliable, independent and objective information about the current state of our natural heritage, and how government decisions influence its trajectory. That’s a critical role that TSC 2.0 should play.

Expertise will be crucial for the new appointee. Given the complex science of species conservation, a background in environmental science is a clear requirement, just as a background in economics would be expected for the chair of the Productivity Commission, or a grounding in law for a human rights commissioner.

For a commissioner to work effectively, they must also be willing to comment on politically sensitive issues and put themselves at odds with the government when necessary. Commissioners typically work as the head of an independent statutory body, such as the Productivity Commission, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, and the Australian Electoral Commission.

However, the TSC position sits within the Department of Environment and Energy and so, like any public servant, the commissioner is restricted in what they can say in public forums. A more accurate name for the current position would be Threatened Species Ambassador.

But if the TSC 2.0 is to be a truly informed and independent voice for Australia’s threatened species, the role must sit within a statutory authority, at arm’s length from government. This is the case in New Zealand, where an independent environment commission has operated since 1986. It’s time for Australia to follow suit.

Authors: Euan Ritchie, Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

Read more http://theconversation.com/australias-species-need-an-independent-champion-83580