New research reveals the origin of Australia’s extinct flightless giants, the mihirung birds

- Written by Trevor H. Worthy, Associate professor, Flinders University

Australia’s living flightless birds - the emu and close relative the cassowary - once roamed alongside much larger birds that resembled dinosaurs.

These huge creatures are known as mihirungs, based on the Aboriginal term for “giant bird”.

The mihirungs not only reached much larger sizes than emus, cassowaries, ostriches, kiwis and kin (known collectively as ratites), but were much more intimidating in appearance. Unlike the small-headed ratites, they had massive skulls, with sail-like bills.

Read more: Tall turkeys and nuggety chickens: large ‘megapode’ birds once lived across Australia

Even the smallest of these mihirungs was as large as an emu, while others grew to the size of a horse, with males weighing up to 650kg. Despite their size, all were gentle giants, browsing on fruit and leaves of shrubs.

In a study published today in Royal Society Open Science, we looked at the origin of these mihirungs, which had been a mystery.

There have been repeated suggestions that they were related to waterfowl such as ducks and geese, but hard data was scarce.

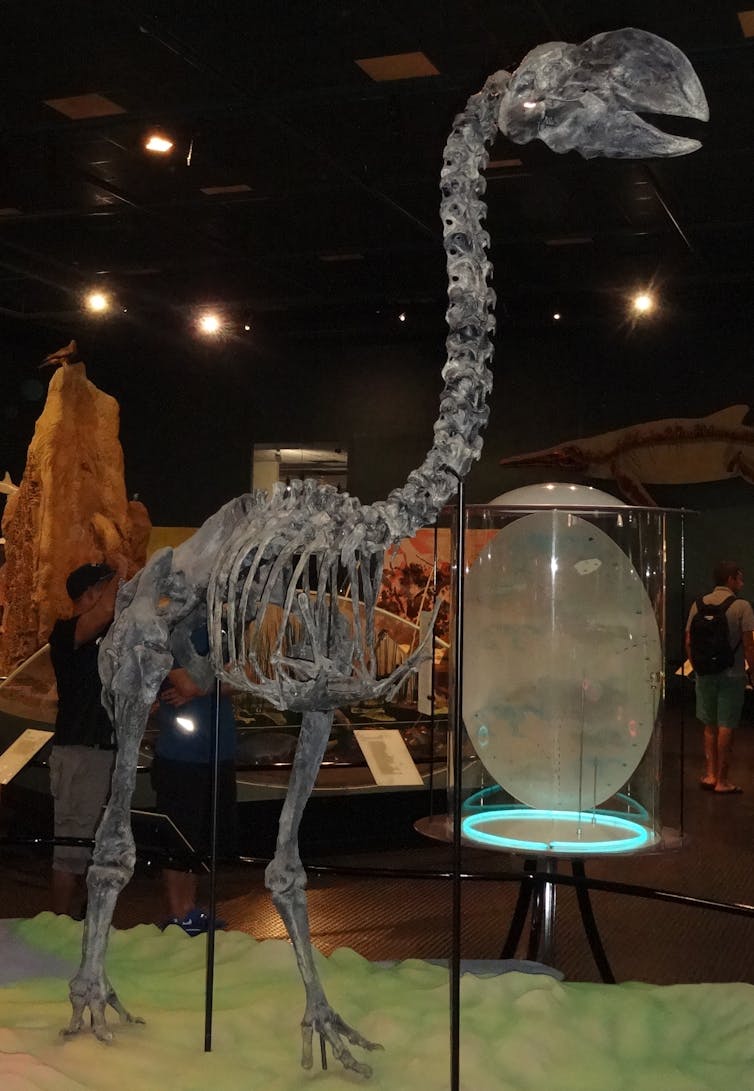

A skeleton of Dromornis planei, an extinct giant mihirung bird from Australia, on display in Darwin. The enormous head and bill are only slightly exaggerated by camera angle.

Michael Lee, Flinders University and South Australian Museum

A skeleton of Dromornis planei, an extinct giant mihirung bird from Australia, on display in Darwin. The enormous head and bill are only slightly exaggerated by camera angle.

Michael Lee, Flinders University and South Australian Museum

Evolutionary trees and ancient ducks

We compared mihirungs (scientific name Dromornithidae) to a range of potential relatives, to work out a new evolutionary family tree of major bird lineages.

These included the gastornithids, such as Gastornis giganteus of North America and G. parisiensis of Europe, giant herbivores that went extinct about 50 million years ago.

We also included a selection of modern birds (including ratites, waterfowl and landfowl, and cranes) and key fossil taxa such as Vegavis (a diving bird that lived during dinosaur age) and flamingo-like ducks or presbyornithids.

We also included the largest bird from South America, the extinct Brontornis burmeisteri, and terror birds (Phorusrhacidae) such as Patagornis marshi in the analysis.

The branching pattern in the evolutionary tree we obtained revealed some intriguing relationships.

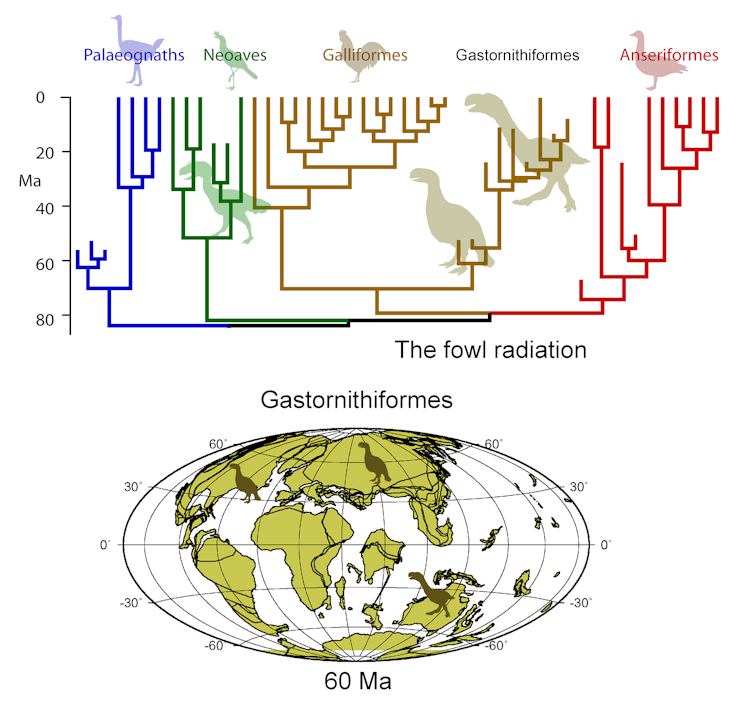

A simplified family tree of giant fowl showing how the ratite palaeognaths are the sister group of other modern birds. Among those, the Neoaves are the sister group to all fowl. The fowl include chicken and kin (Galliformes), waterfowl (Anseriformes), and the giant fowl (Gastornithiformes) including the mihirungs. The map shows the earth 60 million years ago and where the gastornithiforms lived.

Worthy et al, Author provided

A simplified family tree of giant fowl showing how the ratite palaeognaths are the sister group of other modern birds. Among those, the Neoaves are the sister group to all fowl. The fowl include chicken and kin (Galliformes), waterfowl (Anseriformes), and the giant fowl (Gastornithiformes) including the mihirungs. The map shows the earth 60 million years ago and where the gastornithiforms lived.

Worthy et al, Author provided

For a start, Vegavis was more primitive than currently thought. It was previously interpreted as a genuine duck (anseriform), with its great age (66 million years old) implying that modern birds diversified very early, deep inside the dinosaur age.

But our analysis shows that Vegavis is not a duck. Rather, it is a distant cousin of all fowl (ducks, geese, chickens, and so on).

This much more primitive position on the avian tree fits more with its geological antiquity - and has important implications for molecular dating, which has previously used Vegavis to calibrate an ancient age of ducks and therefore of all living birds.

Where do Australia’s giant birds come from?

A surprising result of the research is that the mihirungs of Australia were not particularly closely related to living waterfowl.

Rather, they grouped with giant flightless birds from the Northern Hemisphere, the gastornithids. We termed this previously unrecognised grouping the new order Gastornithiformes. This group is a distant relative of all fowl.

How did these large, non-flying birds move between Australia and Eurasia? They could hardly have walked across the ocean.

The most plausible scenario is that the early members of both groups were smaller flying birds, perhaps partridge-sized, which could traverse oceans and continents.

Flightless and gigantism then evolved separately in lineages which settled down in Australia and in Eurasia - perhaps around 60 million years ago, when there was a paucity of large herbivores due to the extinction of the dinosaurs.

The evolutionary story of giant fowl thus parallels the ratites. Our collaborators have recently shown the closest relative of the New Zealand kiwi is the extinct Madagascan elephant bird, and the only plausible scenario there is that their immediate common ancestor was a widely dispersing flyer.

These giant mihirungs and gastornithids evolved along their own path and came to look nothing like typical land fowl or waterfowl. They all had an oversized head with a deep narrow bill.

An odd feature of this bill was that the horny covering (that typically covers the entire bill) was restricted to the biting parts. The upper half was covered in soft tissue and richly supplied by blood vessels.

It may have been used in courtship displays, and one sex might have been particularly brightly coloured.

Though the Australian mihirungs and Eurasian gastornithids are close cousins, they not related to giants from South America. That continent’s largest bird, Brontornis burmeisteri, was shown to be most closely related to the carnivorous terror birds (Phorusrhacidae).

Unlike its more slender relatives, Brontornis was likely a specialist scavenger and used its size to escape predators.

The last giants

In the immediate aftermath of the extinctions of the (non-avian) dinosaurs, the dawn of the age of mammals was actually the brief age of giant birds.

The niches vacated by dinosaurs were filled by the huge flightless birds: mihirungs in Australia, gastornithids in Eurasia and terror birds in South America.

Not long after, the familiar ratites also evolved separately on different continents, and even major oceanic islands such as New Zealand (moas and kiwis) and Madagascar (elephant birds).

Read more: A case of mistaken identity for Australia’s extinct big bird

Of this large flightless menagerie, only the ratites survive today. The gastornithids in the Northern Hemisphere became extinct 50-40 million years ago, and the terror birds of South America in the early Pleistocene about 1.8 million years ago.

But the dromornithids, after surviving as a group for more 60 million years in Australia until the Pleistocene, went extinct shortly after humans arrived within the last 65,000 years - when the last species Genyornis newtoni disappeared.

It is likely that these reminders of the dinosaur age could not withstand the new combination of habitat changes and predation, of both the birds and their eggs, wrought by humans.

Authors: Trevor H. Worthy, Associate professor, Flinders University