Isolation, collapsing lungs and spitting bans: three ways we used to treat TB, and still might

- Written by Rebecca Le Get, PhD Candidate, La Trobe University

Tuberculosis (TB) has been responsible for more deaths than any other infectious disease in human history. It is one of the world’s top ten causes of death today.

It is estimated that a third of the world’s population have been infected with TB. But for most of those infected, their immune systems are keeping it in check so they are not actively contagious.

There is a 10% risk that once infected with TB it will progress to active disease, which often attacks and damages the lungs, creating lesions. This can cause symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, chest pains, weakness, and coughing up blood. TB is spread when someone with an active lung infection coughs, sneezes, sings, or laughs, and the exhaled bacteria are inhaled by those nearby.

Read more: What is TB and am I at risk of getting it in Australia?

Although it is not a disease we think about often in Australia, TB has had a significant impact on the world, from influencing fashion trends to helping understand how the human body works.

Don’t spit!

It was confirmed in the 1880s that TB is a contagious disease, spread through coughing and sputum. Sputum is the liquid that comes from your respiratory tract when you cough and contains contains mucus, bacteria, and other cellular fragments.

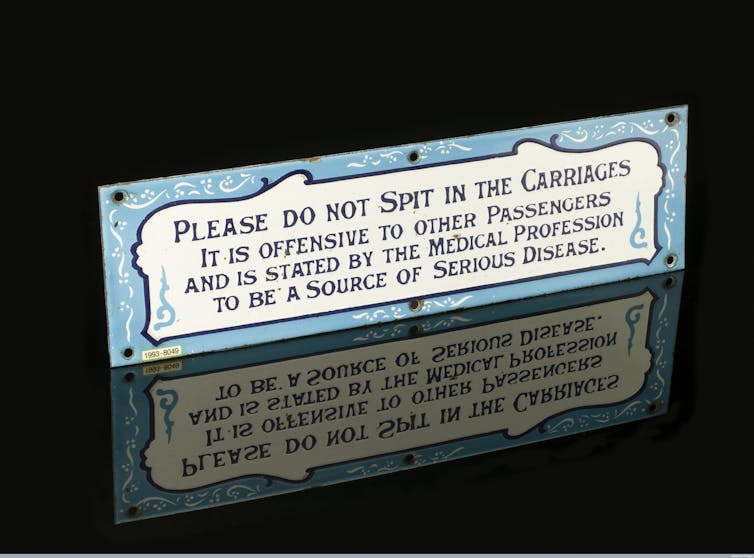

Public health campaigns sprouted up around Australia and other Western countries to contain TB’s spread by discouraging people from spitting on walls, trains and in the streets. These included signs and posters telling people not to spit.

If you did need to cough, people were encouraged to do so into disposable items such as cloths or paper napkins that could be burned.

This sign was used on Great Southern & Western Railways in Ireland to prevent the spread of disease.

wellcome images, CC BY

This sign was used on Great Southern & Western Railways in Ireland to prevent the spread of disease.

wellcome images, CC BY

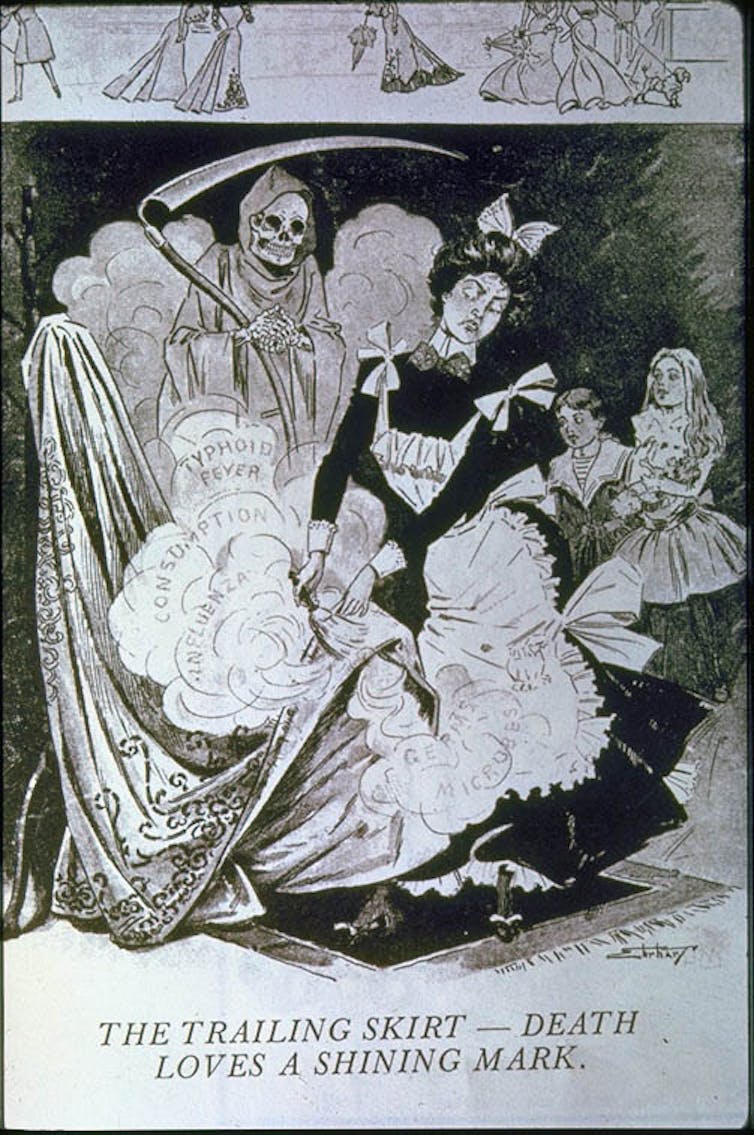

By the turn of the 20th century, fear of TB germs was so strong that it extended to women’s floor-length dresses. The concern was that trailing hems could drag through pools of sputum and thence introduce TB into homes. So we can thank TB for the rising hemlines on dresses and skirts.

Men were not immune to these fashion shifts either. Their full beards and moustaches were considered unhygienic and liable to hide germs. So a clean-shaven look was encouraged.

We can thank TB for the rising hemlines on skirts.

The Trailing Skirt - Death Loves a Shining Mary 1900/Marchand Archive

We can thank TB for the rising hemlines on skirts.

The Trailing Skirt - Death Loves a Shining Mary 1900/Marchand Archive

Collapsing lungs and surgery

It was believed lungs may need to have a rest, which would give lesions caused by tuberculosis a chance to heal. So the lung was deliberately collapsed though a technique used from 1882 onwards.

This was done by injecting oxygen or nitrogen into the chest cavity and increasing the pressure until the lung collapsed. The collapse wasn’t permanent, so patients had to receive a further top-up of gas every few weeks to continue the treatment. It has been estimated that more than 100,000 patients were treated in this manner in the 25 years after this technique was developed. But there were no rigorous studies conducted at the time to confirm its effectiveness.

A pneumothorax device, used to collapse the lung.

Wikimedia Commons

A pneumothorax device, used to collapse the lung.

Wikimedia Commons

Another reversible treatment that became popular in the 1930s and 1940s was called phrenic paralysis. Here, a patient’s lungs were examined for lesions, and the phrenic nerve, which runs beside the lung and needed to be treated, was crushed. This would cause the diaphragm on that side to be paralysed and no longer contract. That lung would no longer inflate and deflate until the nerve healed.

But the most invasive and permanent method to collapse the lungs was the removal of ribs from 1885 onwards, called thoracoplasty. By removing portions of the skeleton, which supports the chest wall, the lung collapses and is permanently at rest. It’s now believed this technique was effective because the TB bacteria require oxygen to survive, but the complications of such surgery could be disfiguring or even fatal.

Thoracic surgery continues to be used to treat antibiotic-resistant TB today. This is where the infectious lesions and the surrounding lung tissue are cut out. And if it weren’t for the development of these surgical techniques in TB, those same skills would not exist to be used today against diseases such as lung cancer.

Isolation and rest

From the middle of the 19th century, until the latter half of the 20th, people with TB were confined in specialised hospitals called sanatoria.

In Australia and elsewhere, patients were often placed outside under verandas or on balconies, or in open-sided structures that were little more than sheds. The hope was that by exposing patients to fresh air, they would be cured.

Sun parlour in a tubercular hospital in Dayton, Ohio 1910-1920.

Library of Congress

Sun parlour in a tubercular hospital in Dayton, Ohio 1910-1920.

Library of Congress

It was not until the discovery of effective antibiotics in the 1940s that TB became truly curable. These days, an increase in the number of antibiotic-resistant TB cases sometimes requires lengthy periods of isolation while taking complex cocktails of drugs, until the patient is no longer infectious.

In Australia, this isolation no longer happens in sanatoria, but in isolation rooms in general hospitals.

Read more: Time to turn back the tide of drug-resistant tuberculosis

Christiaan Van Vuuren’s videos from his time in quarantine in Sydney, give us a glimpse into how hospital treatment for drug-resistant TB in the early 21st century has changed from how patients were cared for in early 20th century sanatoria. But it also shows isolation continues to be an important part of protecting the wider public from infectious disease.

Christiaan Van Vuuren shares his experiences confined to an isolation ward in Sydney.Authors: Rebecca Le Get, PhD Candidate, La Trobe University