Disco ain't dead: how Beyoncé resurrected dance music and its queer history for Renaissance

- Written by David Burton, Lecturer, Theatre, University of Southern Queensland

If you felt the world stop turning for a moment in July, it’s because Beyoncé dropped her new album, Renaissance.

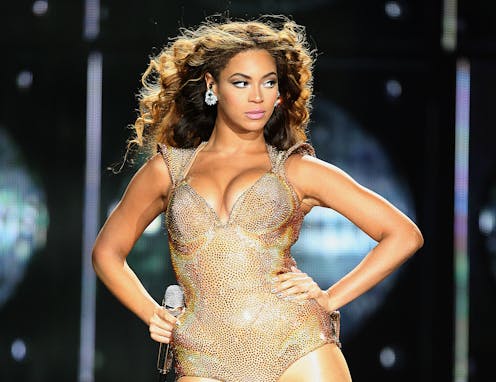

Rolling Stone has described her as the world’s “greatest living entertainer”, with a stardom that intersects fashion, dance, multiple genres of music and visual albums.

Renaissance is her seventh solo studio album, and her first in five years. It is being widely acclaimed as an “immaculate” dance record.

Part of Beyoncé’s continued success involves her sampling from a diverse range of artists across history to layer and create new meaning. She has done this repeatedly as a way of showcasing African artists, and on Renaissance she pays special tribute to house and disco music, and especially it’s queer history.

In fact, the entire album is dedicated to her late gay Uncle Johnny. “He was my godmother and the first person to expose me to a lot of the music and culture that serve as inspiration for this album,” Beyonce wrote.

Thank you to all the pioneers who originate culture, to all of the fallen angels whose contributions have gone unrecognised for far too long.

The first single from the album, Break My Soul, features two key samples and songwriting credits. The first is New Orleans artist Big Freedia, previously featured on Beyoncé’s 2016 Formation. The second is from Show Me Love by Robin S., a song that typifies the house genre that grew from the 80s and became mainstream in the 90s.

The use of house music throughout the album, and her sampling of queer artists such as Big Freedia, points to a queer history of disco and house music that was once controversial enough to cause public riots.

Read more: It's Beyoncé's world. We're just living in it

The day they killed disco

On a warm night in July 1979, disco was murdered.

Referred to as “Disco Demolition Night”, 50,000 people showed up to a baseball park in Chicago to watch a crate of disco records be blown up. In the aftermath, the crowd rushed onto the field. A riot followed in which over 30 people were arrested and many were injured.

Disco had grown in popularity across the 1970s reaching its apex with the release of Saturday Night Fever in 1977. A concentrated rebellion against the genre grew in popularity among rock music fans, who felt the genre was too fixated on mechanical sounds that lacked authenticity.

Rock fans genuinely feared they would lose out to disco, but it is difficult to separate their fears from racism and homophobia.

John Travolta’s starring role in Saturday Night Fever in 1977 presented a different version of masculinity, concerned with fashion and dancing. Acts such as The Village People did little to ease fears of the death of rock and roll. The gradual rise in gay and queer visibility in New York and San Francisco, particularly in music clubs, were also seen as a threat.

Critics have since identified the anti-disco movement as almost completely populated by white men between 18-37. The leader of the movement was radio DJ Steve Dahl and in the weeks leading up to the explosive protest, Dahl and press agencies covering the movement conflated disco with R&B and funk music, and with gay men.

Disco Demolition Night was the climax of a protest years in the making. To a certain extent, it was successful in its desire to kill disco. In the years that followed, disco disappeared off the charts and glam-rock began to take its place.

The artists and audiences who adored disco were forced underground, particularly the queer community, and such was the birth of house music.

Read more: Beyoncé is cutting a sample of Milkshake out of her new song – but not because she 'stole' it

Don’t stop the beat

As disco declined in popularity, artists were no longer able to afford the lush sounds of a full orchestral backing, forcing a reliance on cheaper, synthetic sounds. Disco clubs moved to literal warehouses, giving house music its name.

House music, like disco, is dance music for clubs. It focuses on mechanical sounds, fixed tempos and repetitive sounds. By the 1990s, thanks to hits like Show Me Love by Robin S., house music became mainstream, and was used by Cher, Madonna, Kylie Minogue and even Aqua’s quintessential 90s pop hit Barbie Girl.

In recent years, disco has seen a steady re-emergence, spearheaded by producers such as Pharrell, who collaborated with Daft Punk for the 2013 hit Lose Yourself to Dance. Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia (2020) was a finely crafted, album length tribute to disco music.

Beyoncé’s new album also features a pantheon of other queer artists (Ts Madison, Honey Dijon, Syd, Moi Renee, MikeQ and Kevin Aviance), and is deliberately designed to be played in dance clubs. In contrast to her other albums, each track blends seamlessly into the next, as if the entire album is an elongated DJ set.

Beyoncé has been particularly open about the release of an acapella and instrumental versions of Break My Soul for use by DJs who may remix the work. She has even released a new remix of the single featuring Madonna.

Beyoncé’s Renaissance may secure 2022 as the year disco and house fulfilled their resurrection. Lizzo’s new album, Special, features About Damn Time, a retro-disco dance hit that is currently sitting at the top of America’s Billboard charts.

These female artists follow a trend already set by Cher, Madonna and Kylie Minogue, who publicly ally themselves with the queer community and deliberate create dance albums for their dedicated audience. In doing so, they have become the biggest pop stars of their time.

Read more: Beyoncé has helped usher in a renaissance for African artists

Authors: David Burton, Lecturer, Theatre, University of Southern Queensland