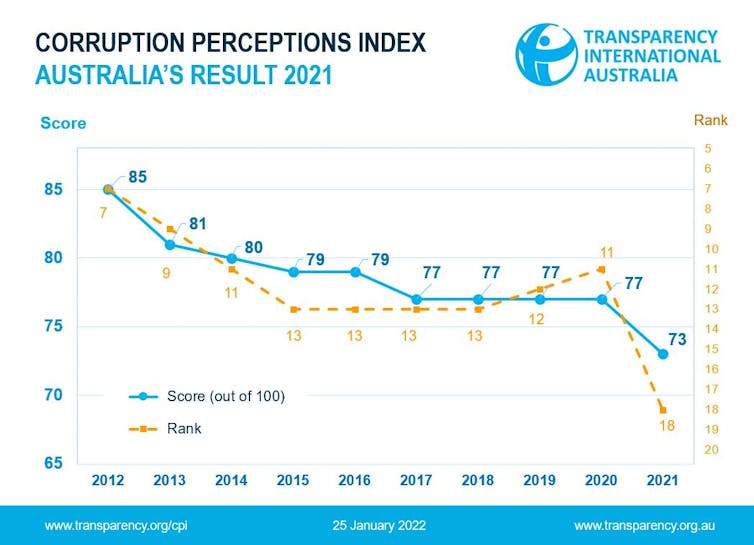

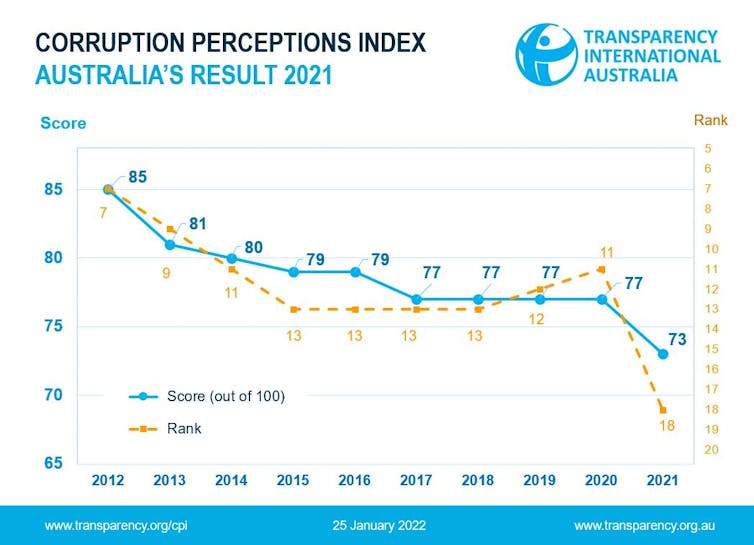

In a worrying sign, Australia has plummeted in Transparency International’s latest Corruption Perceptions Index – the world’s most widely cited ranking of how clean or corrupt every country’s public sector is believed to be.

In the 2021 index released today, Australia has repeated its largest-ever annual drop – falling four points on the 100-point scale, from 77 to 73. Zero is considered highly corrupt, while a score of 100 is very clean.

Overall, Australia has dropped 12 points on the index since 2012, more than any OECD country apart from Hungary, which also fell 12 points. Australia’s rate of decline is also similar or steeper than other countries with far worse issues, including Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria and Venezuela.

Australia was ranked seventh in the world in 2012, level with Norway. This year, Australia has fallen to 18th out of 180 countries. In contrast, Norway’s global standing has improved, climbing from seventh to fourth on the index.

It’s a clear sign Australia has missed a huge chance to correct our failing anti-corruption reputation. And this will likely continue to fall unless integrity policies are turned around at this year’s federal election.

Author provided

Australia had the chance to stem the fall

Before this year, Australia’s score on the index had levelled off as the federal government finally made pledges to address integrity issues and other efforts to root out corruption took place.

In that period, there was hope things might turn around:

corrupt politicians and officials were successfully convicted in several states (including NSW’s prosecution of former ministers Eddie Obeid and Ian Macdonald, while action was taken against local government corruption in Queensland)

Former Labor minister Eddie Obeid was sentenced last year to seven years over a rigged mining tender.

Bianca de Marchi/AAP

after many years, the major parties finally pledged to establish a federal integrity commission (Labor in February 2018 and the Coalition in December 2018)

long-overdue legislation was introduced to parliament to enhance laws against bribery of foreign officials

bipartisan recommendations were made to strengthen whistleblower protections, with new laws on private sector whistleblowing and promises of reform for the federal public sector

high-profile federal enforcement action was taken against money laundering through Australian banks, while growing evidence of money laundering in casinos and real estate raised hopes of further reform.

But the last year has seen progress stalled

The latest drop in the CPI shows business and expert confidence in Australia’s official responses to corruption has collapsed again.

Since 2020, when the data for this year’s index were mostly collected, the expected progress has not happened. Instead, Australia has seen:

Former Labor minister Eddie Obeid was sentenced last year to seven years over a rigged mining tender.

Bianca de Marchi/AAP

after many years, the major parties finally pledged to establish a federal integrity commission (Labor in February 2018 and the Coalition in December 2018)

long-overdue legislation was introduced to parliament to enhance laws against bribery of foreign officials

bipartisan recommendations were made to strengthen whistleblower protections, with new laws on private sector whistleblowing and promises of reform for the federal public sector

high-profile federal enforcement action was taken against money laundering through Australian banks, while growing evidence of money laundering in casinos and real estate raised hopes of further reform.

But the last year has seen progress stalled

The latest drop in the CPI shows business and expert confidence in Australia’s official responses to corruption has collapsed again.

Since 2020, when the data for this year’s index were mostly collected, the expected progress has not happened. Instead, Australia has seen:

Bridget McKenzie quit the front bench and resigned as deputy Nationals leader after the so-called ‘sports rorts’ affair.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

Bridget McKenzie quit the front bench and resigned as deputy Nationals leader after the so-called ‘sports rorts’ affair.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian announcing her resignation last October.

Bianca de Marchi/AAP

Why leadership is key

It doesn’t have to be this way. Transparency International has used this year’s global index to highlight the need for countries to improve checks and balances through strong integrity institutions and to uphold people’s rights to hold those in power to account.

When countries show serious leadership in anti-corruption reform – such as the United Kingdom during David Cameron’s Conservative government from 2012–17 - their scores on the index can climb.

Clearly, the world now fears this type of leadership is lacking in Australia.

The priorities and potential solutions are increasingly understood by experts, observers and the community. For example, Griffith University and Transparency International Australia recently assessed Australia’s national integrity system and developed a reform blueprint to follow.

With the 2022 federal election now just months away, the quality of the parties’ anti-corruption commitments – and leaders’ willingness to implement them – will matter as never before.

Key issues still hang in the balance. As recently as November, the prime minister and attorney-general revealed they were shelving any improvements to their Commonwealth integrity commission plan.

This announcement came despite the government having spent yet another year consulting over the plan’s obvious problems.

Read more:

Explainer: what is the proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission and how would it work?

Anti-corruption reform is no longer the “fringe issue” Prime Minister Scott Morrison claimed it was several years ago.

For confidence in Australia’s public integrity to improve, the winner of the election is going to need to promise – and deliver – more convincing solutions than we’ve seen in the last two years.

Authors: A J Brown, Professor of Public Policy & Law, Centre for Governance & Public Policy, Griffith University

NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian announcing her resignation last October.

Bianca de Marchi/AAP

Why leadership is key

It doesn’t have to be this way. Transparency International has used this year’s global index to highlight the need for countries to improve checks and balances through strong integrity institutions and to uphold people’s rights to hold those in power to account.

When countries show serious leadership in anti-corruption reform – such as the United Kingdom during David Cameron’s Conservative government from 2012–17 - their scores on the index can climb.

Clearly, the world now fears this type of leadership is lacking in Australia.

The priorities and potential solutions are increasingly understood by experts, observers and the community. For example, Griffith University and Transparency International Australia recently assessed Australia’s national integrity system and developed a reform blueprint to follow.

With the 2022 federal election now just months away, the quality of the parties’ anti-corruption commitments – and leaders’ willingness to implement them – will matter as never before.

Key issues still hang in the balance. As recently as November, the prime minister and attorney-general revealed they were shelving any improvements to their Commonwealth integrity commission plan.

This announcement came despite the government having spent yet another year consulting over the plan’s obvious problems.

Read more:

Explainer: what is the proposed Commonwealth Integrity Commission and how would it work?

Anti-corruption reform is no longer the “fringe issue” Prime Minister Scott Morrison claimed it was several years ago.

For confidence in Australia’s public integrity to improve, the winner of the election is going to need to promise – and deliver – more convincing solutions than we’ve seen in the last two years.

Authors: A J Brown, Professor of Public Policy & Law, Centre for Governance & Public Policy, Griffith UniversityRead more